Hope I picked the right side. She's so thin. I've gotten away with this before, but you never know, do you? I wonder if there'll be enough tissue... Such a nice lady... Antibiotics? What about the irrigation fluid, antibiotics there, too? Figures: the vein looks tiny. Micropuncture'll probably be easier. We'll numb her up well - can never have enough anesthetic. We'll work lateral. Grab some more. Then medial, A bit more. Then one a bit deeper to numb the pre-pec fascia. Good. Blade. Why can't they use the 15 blade? Damb 10-blade's so big. Gotta remind 'em to change that. Okay, Bovie. Nice. Not much tissue here. Damn mastectomies; bilateral, no less. We should be fine. There's a little more tissue here and if we extend the pocket this way. Yeah, should be fine. Now, ultrasound. Hope we get it on the first pass. Come on... Okay, there's the blood. Seems to be flowing freely. Wire. Good. Hmmm, resistance. Flouro. The first part looks okay. Why won't the wire pass? You don't get many tries if you miss... Pull back. There. Now advance. Come on, come ON! There. Feels good. Fluoro. Oh, thank God! Normal course. Angle to the SVC looks pretty acute. Dilate, Preform the sheath - hope it doesn't kink. Good. Wire passes fine. I wonder if I should doble wire this. Yeah, safer, especially this time of night. Good choice. One lead at a time. Counter-clock. Septal. Stylette back. Nice. Let's try here. Alright, maybe a bit more apical. Better. Those are decent R waves. 10 turns. Nice injury current. Threshold? Perfect. It'll be 0.5 mV in the morning. Keep moving. Pre-pec fascia first. Make sure there's enough lead. Perfect. Three ties to the muscle then tie the lead. Be sure I'm over the sewing sleeve. Good and tight. Yeah, it looks pinched. Leave a 1/4" of suture. Cut. Now the A lead. Big atrium. Blue stylette. Nice movement. Good. Try here. Excellent. 10 turns, screw's out. I like the movement. Nice injury current. Same thing. 2-0 Ethibond, good and tight. Again. Good. Leads lie smoothly on the floor of the pocket. Seems to be a bit of tissue there. Bovie. Good. Check for bleeders. Bovie. Let's irrigate. Look again. A bit more. Okay. Should be fine. New gloves. Device? Atrium first - don't drop it. Never forget when I did that once. Set screw looks good. A little tug. Nice. Ventricular lead. I see the distal lead tip in the header - perfect. I like lots of clicks. Leads have to lie flat. No protruding. Good. 2-0 now to secure the header. I think there'll be enough tissue. Gotta be careful about this closure. Bury the knots. Coming together pretty well. Should be enough tissue. 3-0. Good. Too much dimpling. Try that one again. Better. 4-0 layer. Nice. No pressure on the skin. Run it carefully. Bury the knot. Good. Benzoin? Steri-strips. Make sure they lie flat. Good. Gauze dressing. Tegaderm. I think we'll be okay. No swelling, dressing dry.

"All done, Mrs Smith. You did great! No problem at all. Just gotta watch for arm swelling, as we discussed, okay?"

-Wes

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Friday, February 24, 2012

Teaching Old Dogs

I guess I've now become an "old dog" in medicine. The residents look younger, the fellows, sharp and trim, and some of my contemporary physicians, like well-worn time-pieces, are beginning to complain of sore knees, backs, and declining vision. And then there's the nocturia...

Ugh.

But for those of us who've been around the block a bit, there remains the constant desire to remain up-to-date, novel, even original. So we try new new things. Sometimes they work for us, sometimes they don't. One thing's for certain, however, it's much harder for salespeople to sway us old dogs, because by now, many of our habits are based on past experiences, not press releases.

Take for instance, three-dimensional mapping in the EP lab. It's cool stuff: electrodes or magnets are arranged around the patient to create an X, Y, Z coordinate system of sorts, and a catheter is moved about inside the coordinate system to locate structures, map arrhythmias, and to facilitate movements of catheters without x-ray guidance. The pictures are multicolor and stunning. They are also typically studded with little circular dots placed in locations chosen by a technician to look stunning. Sometimes, this technology makes a critical difference in the outcome of a case. Other times, it's probably a waste of money, since some arrhythmias are defined by very well-defined anatomic locales whose need for precisely localized ablation lesions are simply not necessary.

So I was surprised to hear one industry rep remark that "every" new fellow uses 3-D mapping systems these days to ablate anything. Maybe he was selling his system, maybe not. But I wondered: Really? Even for something as straightforward as a typical atrial flutter ablation? "Yeah," he said. "They don't know how to map the old fashion way like you (older) guys do."

Maybe that's a good thing. Maybe not. There's much more to successful ablation than locating a catheter in three-dimensional space or placing a dot on an artificially-created geometric surface. Yet these days, I rarely hear people speak about catheter stability, injury current, unipolar electrograms, or polarity reversal any more. Instead, when using these 3-D mapping systems, catheter ablation it sounds more like a game of connect-the-dots: "You've got a gap over there."

So too, with our ablation technology.

This week I finally broke down and tried irrigated ablation catheters for ablation and my experience? Underwhelming. There was extra tubing, a stiff catheter, fluid burdens I never had to think about before, and an inability to have any surrogate for catheter contact (such as tip temperature). In return, I received only a promise of larger lesions, simpler ablation before the case started yet found myself struggling to complete a relatively simple procedure. Certainly there was plenty that was new and unfamiliar: new catheters, new technology, new anecdotes to remember. But at the end of both cases I performed, I found myself moving back to a conventional non-irrigated ablation catheter to achieve success. Needless to say, this ol' dog wasn't impressed.

Now I know there are irrigated ablation catheter proponents out there. They sing its praises and wouldn't perform catheter ablation with anything but this technology. But I wonder how many of them ever looked at the physiology of what they're doing. Years ago, I performed sinus node ablation in dogs with 50 watts of power using an 8mm tip conventional radiofrequency ablation catheter equipped with temperature feedback. I saw what that much energy did to the dog's heart... and surrounding lungs. I will never forget that finding. My practice in man was forever changed as a result of that opportunity. I find it hard to believe we need more energy than that if there is good catheter contact.

And yet, I now see FDA-approved 100-watt RF generators now and irrigated-tip ablation catheters capable of creating steam pops deep in tissue while having nice cool endocardial tip temperatures displayed that provide an artificial level of reassurance to our younger operators. I know there's a reason these technologies were developed: influential doctors in our EP community demanded they be developed and industry responded. Skill levels of operators are different. It was new and innovative. It promised better outcomes while being acceptably safe, yet without so much as a lick of real-life multi-center case-based post-market proof.

So when I see the relatively high complication risks of atrial fibrillation reported recently, I wonder if some of those complications were from this push to higher power, irrigated-tip ablation catheters capable of making ridiculously larger, deeper ablation lesions in our rush to expedite the procedure couched on the unproven hope that with larger lesions, the need for repeat ablation would be reduced. Is it? Are we creating more problems than those we are hoping to solve? Truth is: we don't know.

Which is exactly why we need an atrial fibrillation registry. It's also why we need studies like the prospective, randomized atrial fibrillation ablation trial like the CABANA (Catheter Ablation versus Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation) trial to begin to answer such complicated questions. Whether there will be enough data for subgroup analysis of irrigated tip ablation catheter from non-irrigated ablation technologies in CABANA remains to be seen. But at least the CABANA investigators didn't require a particular form of energy delivery for the ablation arm of the study. Will there be value in such a subgroup analysis? It will depend on the numbers.

At least this old dog remains happy he can contribute to this arm of the ablation trial and hopefully remain innovative and creative in the years ahead while still practicing on the basis of my experience.

And who knows, maybe one day, we'll make catheter ablation safer for our patients as a result - you know: the old fashioned way.

-Wes

Ugh.

But for those of us who've been around the block a bit, there remains the constant desire to remain up-to-date, novel, even original. So we try new new things. Sometimes they work for us, sometimes they don't. One thing's for certain, however, it's much harder for salespeople to sway us old dogs, because by now, many of our habits are based on past experiences, not press releases.

Take for instance, three-dimensional mapping in the EP lab. It's cool stuff: electrodes or magnets are arranged around the patient to create an X, Y, Z coordinate system of sorts, and a catheter is moved about inside the coordinate system to locate structures, map arrhythmias, and to facilitate movements of catheters without x-ray guidance. The pictures are multicolor and stunning. They are also typically studded with little circular dots placed in locations chosen by a technician to look stunning. Sometimes, this technology makes a critical difference in the outcome of a case. Other times, it's probably a waste of money, since some arrhythmias are defined by very well-defined anatomic locales whose need for precisely localized ablation lesions are simply not necessary.

So I was surprised to hear one industry rep remark that "every" new fellow uses 3-D mapping systems these days to ablate anything. Maybe he was selling his system, maybe not. But I wondered: Really? Even for something as straightforward as a typical atrial flutter ablation? "Yeah," he said. "They don't know how to map the old fashion way like you (older) guys do."

Maybe that's a good thing. Maybe not. There's much more to successful ablation than locating a catheter in three-dimensional space or placing a dot on an artificially-created geometric surface. Yet these days, I rarely hear people speak about catheter stability, injury current, unipolar electrograms, or polarity reversal any more. Instead, when using these 3-D mapping systems, catheter ablation it sounds more like a game of connect-the-dots: "You've got a gap over there."

So too, with our ablation technology.

This week I finally broke down and tried irrigated ablation catheters for ablation and my experience? Underwhelming. There was extra tubing, a stiff catheter, fluid burdens I never had to think about before, and an inability to have any surrogate for catheter contact (such as tip temperature). In return, I received only a promise of larger lesions, simpler ablation before the case started yet found myself struggling to complete a relatively simple procedure. Certainly there was plenty that was new and unfamiliar: new catheters, new technology, new anecdotes to remember. But at the end of both cases I performed, I found myself moving back to a conventional non-irrigated ablation catheter to achieve success. Needless to say, this ol' dog wasn't impressed.

Now I know there are irrigated ablation catheter proponents out there. They sing its praises and wouldn't perform catheter ablation with anything but this technology. But I wonder how many of them ever looked at the physiology of what they're doing. Years ago, I performed sinus node ablation in dogs with 50 watts of power using an 8mm tip conventional radiofrequency ablation catheter equipped with temperature feedback. I saw what that much energy did to the dog's heart... and surrounding lungs. I will never forget that finding. My practice in man was forever changed as a result of that opportunity. I find it hard to believe we need more energy than that if there is good catheter contact.

And yet, I now see FDA-approved 100-watt RF generators now and irrigated-tip ablation catheters capable of creating steam pops deep in tissue while having nice cool endocardial tip temperatures displayed that provide an artificial level of reassurance to our younger operators. I know there's a reason these technologies were developed: influential doctors in our EP community demanded they be developed and industry responded. Skill levels of operators are different. It was new and innovative. It promised better outcomes while being acceptably safe, yet without so much as a lick of real-life multi-center case-based post-market proof.

So when I see the relatively high complication risks of atrial fibrillation reported recently, I wonder if some of those complications were from this push to higher power, irrigated-tip ablation catheters capable of making ridiculously larger, deeper ablation lesions in our rush to expedite the procedure couched on the unproven hope that with larger lesions, the need for repeat ablation would be reduced. Is it? Are we creating more problems than those we are hoping to solve? Truth is: we don't know.

Which is exactly why we need an atrial fibrillation registry. It's also why we need studies like the prospective, randomized atrial fibrillation ablation trial like the CABANA (Catheter Ablation versus Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation) trial to begin to answer such complicated questions. Whether there will be enough data for subgroup analysis of irrigated tip ablation catheter from non-irrigated ablation technologies in CABANA remains to be seen. But at least the CABANA investigators didn't require a particular form of energy delivery for the ablation arm of the study. Will there be value in such a subgroup analysis? It will depend on the numbers.

At least this old dog remains happy he can contribute to this arm of the ablation trial and hopefully remain innovative and creative in the years ahead while still practicing on the basis of my experience.

And who knows, maybe one day, we'll make catheter ablation safer for our patients as a result - you know: the old fashioned way.

-Wes

Wednesday, February 22, 2012

Truth and Consequences: The St. Jude Riata ICD Lead Recall and It's Possible Implications for Durata

Today, a remarkable tour de force essay on the St. Jude Medical Riata defibrillator lead recall controvery written by Edward J Schloss, MD, director of cardiac electrophysiology at Christ Hosptial in Cincinnati, OH, appears at Cardiobrief. It is a must-read for all of us interested in the management of patients with the current class of St. Jude defibrillator leads.

In the essay, he reviews two opposing views on the industry handling of this recall, one published as a perspective piece in the New England Journal of Medicine by Robert Hauser, MD, and the other, a rebuttal piece published by St. Jude Medical's Chief Medical Officer and Senior Vice President of Clinical Affairs, Mark D. Carlson, MD. The article reviews the engineering changes made to the Riata line of leads in its evolution to the Durata defibrillator leads and expresses clear concerns about disclosure of all available information regarding lead characteristics to implanting physicians.

This piece is a must-read for electrophysiologists and industry personnel involved in the care of these complicated patients. Schloss concludes:

-Wes

PS: John Mandrola, MD, a co-editor of Dr. Schloss's piece, also offers an excellent overview of concerns that confront electrophysiologists regarding the Riata/Riata ST lead recall over at theHeart.org.

In the essay, he reviews two opposing views on the industry handling of this recall, one published as a perspective piece in the New England Journal of Medicine by Robert Hauser, MD, and the other, a rebuttal piece published by St. Jude Medical's Chief Medical Officer and Senior Vice President of Clinical Affairs, Mark D. Carlson, MD. The article reviews the engineering changes made to the Riata line of leads in its evolution to the Durata defibrillator leads and expresses clear concerns about disclosure of all available information regarding lead characteristics to implanting physicians.

This piece is a must-read for electrophysiologists and industry personnel involved in the care of these complicated patients. Schloss concludes:

Anyone who has been in the business of cardiac rhythm management has struggled with the problems of device failures. Because most of these only occur years after FDA approval, having a system for early detection of excess or unique failures is critical.Go now. Read it all. You will learn something.

Industry response to these failures is also critical. Clear, honest acknowledgement of the problem is essential. We also need quick action to define the scope of the problem and create an action plan. These measures go a long way to maintaining the confidence of everyone involved, including, but not limited to, physicians, hospitals, patients, and the investment community.

Every time we, the implanting physicians, implant a medical device, we are taking a measured risk that must be outweighed by its benefits. Understanding this true risk, especially in newer devices, is extremely difficult. By becoming a student of the engineering process of these devices, we can become better equipped to make good decisions for our patients.

We are only now learning the scope of the problem with Riata and Riata ST. The lead mechanical failures and externalizations of this lead may only first occur four to five years after implant. Since Durata leads are only now approaching that interval, it is not surprising that we have not seen many troubling signals with this lead. It remains to be seen what the future holds. Until we have longer experience and collect more data, it us up to individual doctors to educate themselves with available clinical and engineering data so they are equipped to make good decisions.

-Wes

PS: John Mandrola, MD, a co-editor of Dr. Schloss's piece, also offers an excellent overview of concerns that confront electrophysiologists regarding the Riata/Riata ST lead recall over at theHeart.org.

Friday, February 17, 2012

Just a Rash

He was referred for consideration of a biventricular ICD implant after a failed attempt at an outside institution. When listening to his lungs posteriorly, a 'little' rash was noted:

-Wes

Click image to enlarge

-Wes

Kicking Cans

The government is remarkably good at kicking cans down the road.

This is the single reason is why government-run health care costs so much.

For instance, we continue to kick the can down the road for the doctor pay fix. Time and time again, we see the Sustained Growth Rate formula fail to be overturned, and instead, Congress vote a few-month reprieve to pay cuts for doctors until they can find another way to either pay those who do the work, or cloak these paycuts in another, less visible and acutely painful way. Look, we all know it's coming: paying a few paultry percent more for primary care while slashing specialists payments 40% was lost on noone.

And now their kicking the ridiculously complex and overly obsessive medical coding scheme called ICD-10 down the road. This morning we hear the purveyors of this money making scheme, the AMA along with their co-dependents at the Health and Human Services claim they will:

Baloney.

Let me clear: doctors are NOT okay with ICD-10. We never have been. Nor will we ever be. It provides NO value to the patient experience. And let me be even clearer: the REAL reason this can is being kicked down the road is because there are not enough programmers in the world capable of debugging and writing the mounds of computer code accross the scores of information systems out there in the time allotted, nor personnel capable of training all the medical coders and the various permutations of "medical providers" out there on how to use this system.

The delay in implementation of ICD-10 and the inherent costs associated with its implementation and delay of implementation has NOTHING to do with doctors.

Yet this coding scheme and bureaucratic delays of things like the doctor pay fix and the implementation of ICD-10 has EVERYTHING to do with how expensive our health care system has become and how expensive government health care is in general. But you will never see the huge costs of all these delays and hand-wringing accounted for in a non-partisan budget office.

Yep, the reality of these inefficiencies within government-run processes are the poster children for why our entire US health care system is so expensive.

-Wes

This is the single reason is why government-run health care costs so much.

For instance, we continue to kick the can down the road for the doctor pay fix. Time and time again, we see the Sustained Growth Rate formula fail to be overturned, and instead, Congress vote a few-month reprieve to pay cuts for doctors until they can find another way to either pay those who do the work, or cloak these paycuts in another, less visible and acutely painful way. Look, we all know it's coming: paying a few paultry percent more for primary care while slashing specialists payments 40% was lost on noone.

And now their kicking the ridiculously complex and overly obsessive medical coding scheme called ICD-10 down the road. This morning we hear the purveyors of this money making scheme, the AMA along with their co-dependents at the Health and Human Services claim they will:

“announce a new compliance date moving forward,” the agency says.As if they really care. Better yet, it's as if doctors were on really okay with this coding scheme, but just a little "administratively burdened."

“We have heard from many in the provider community who have concerns about the administrative burdens they face in the years ahead,” HHS says.

Baloney.

Let me clear: doctors are NOT okay with ICD-10. We never have been. Nor will we ever be. It provides NO value to the patient experience. And let me be even clearer: the REAL reason this can is being kicked down the road is because there are not enough programmers in the world capable of debugging and writing the mounds of computer code accross the scores of information systems out there in the time allotted, nor personnel capable of training all the medical coders and the various permutations of "medical providers" out there on how to use this system.

The delay in implementation of ICD-10 and the inherent costs associated with its implementation and delay of implementation has NOTHING to do with doctors.

Yet this coding scheme and bureaucratic delays of things like the doctor pay fix and the implementation of ICD-10 has EVERYTHING to do with how expensive our health care system has become and how expensive government health care is in general. But you will never see the huge costs of all these delays and hand-wringing accounted for in a non-partisan budget office.

Yep, the reality of these inefficiencies within government-run processes are the poster children for why our entire US health care system is so expensive.

-Wes

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

The Riata ICD Lead Recall: Two Perspectives

Robert Hauser, MD published a perspective piece in the New England Journal of Medicine today entitled "Here We Go Again — Another Failure of Postmarketing Device Surveillance." In the piece, he offers these suggestions on how to detect these failures earlier:

What is clear, though, is that the efforts to prevent such widespread recalls continue and doctors (as shown by these two perspectives) remain eager to participate in the process.

-Wes

Opportunities have emerged for automated tools to prospectively monitor multicenter device databases for early, low-frequency adverse events and to compare suspect devices with established products that have been shown to be reliable.(4) The goal is a postmarketing surveillance system that not only detects device problems early but also accumulates the data needed to guide patient care. Until such a system exists, St. Jude Medical should initiate a study with these attributes for recalled Riata and Riata ST leads and for the currently marketed Durata leads. Indeed, all manufacturers should conduct postmarketing studies of this type for marketed class III devices that sustain or support life.Jay Schloss, MD offers another thoughtful perspective on this issue in his guest post over on Cardiobrief:

It has been 3 years since the FDA launched the Sentinel Initiative, as Congress, in 2007, directed it to do.(5) The intent of this new system is to supplement the current passive adverse-event reporting with an active, real-time network capable of identifying any safety or efficacy issues soon after a new drug or device is marketed and then communicating the information in a timely manner to health care providers and the public. Creating such a system is an ambitious undertaking, and the initiative aims to gather electronic health data from 100 million people by the end of 2012. Formidable challenges lie ahead, such as setting priorities, developing analytic tools, and deciding when and how to alert the public if a safety signal is detected. Thus, we are years away from a fully operational Sentinel Network.

It is worth noting that all high impact device failures in the cardiac rhythm device industry have occurred well after device approval. In most cases, failures have been rare events occurring many years after these devices became clinically available. The industry is littered with high profile device failures, some of which serve now as footnotes or memories from the more gray haired members of the EP community: Medtronic polyurethane pacing leads, Ventitex Cadence ICDs, and Telectronics Accufix pacing leads were all devices that failed well after they had been introduced to the market. It was through case reports from concerned doctors – not the FDA — that these problems were brought to light.Neither author mentions how their approaches might be funded. Nor is there a clear consensus on how to determine a threshold for sounding a recall (or "advisory"). Should it be announced before a root cause of the problem is known or suspected, or after? Pulling a recall trigger too early before a root cause of the defect is identified leaves doctors and patients completely in the dark about how to manage these complicated situations. These issues are still debated today.

Trying to absolutely prevent the failure of medical devices through the FDA approval process would be challenging to say the least. This would require an anticipation of the potential failure mechanism before the fact to design a study that would detect said defect. Moreover, the number of patients and length of study for these trials would be daunting, impractical and quite likely prohibitively expensive.

Hauser’s call to enforce a robust active postmarket surveillance system would allow ongoing innovation and appropriately timed approval of new technology. With the ability to carefully monitor a large population of approved devices “in the field,” sentinel failures could be detected and acted upon as they occur. With public reporting of these events, doctors could draw their own conclusion of whether to keep implanting these devices and prospective studies could then be designed promptly to determine the scope of the problem. That would be a system that protects patients while still allowing innovation.

What is clear, though, is that the efforts to prevent such widespread recalls continue and doctors (as shown by these two perspectives) remain eager to participate in the process.

-Wes

Our New Electrophysiology Annex?

This was spotted by one of our nurse practitioners vacationing in Belize:

-Wes

Click image to enlarge

-Wes

Happy Valentine's Day Edition of Grand Rounds Is Up!

For all the mended hearts, broken hearts, lonely hearts, sweet hearts, crazy hearts, bitter hearts, joyful and happy hearts out there, John Mandrola, MD hosts this week's edition of the medical blog-o-sphere's Grand Rounds at his blog, Dr. John M.

Happy Valentine's Day!

-Wes

Happy Valentine's Day!

-Wes

Saturday, February 11, 2012

Tremors

I am seeing the world of medicine change before my eyes, and I wonder where we’re going.

Never before has there been more information at our disposal, yet more confusion. Like molecules being heated, the Brownian motion happening in medicine seems completely ineffectual for those of us on the front lines of care, geared more toward expensive facades than substance.

For the most part, doctors keep their heads down. Most of us are busy caring for patients, pushing to get home at least once each week before dinner. Most are humble servants to their patients, working tirelessly for their benefit. Sure, there are a few doctors participating in policy or medical associations, but it's clear to the rank and file that their leadership has already cashed out from patient care and are no longer participants in what medicine has become today. Worse: they’re too few in number and too underfunded and occassionally displayed as hood ornaments to validate a central policy decision.

Then there's call. No one likes call, but it must be covered. Doctors understand that medicine is 24/7/365 affair. But there's more people now, more places, and yes, more call. The burden falls on the doctors, so the tremors resonate louder. No large ones, mind you. But they're happening. Doctors are pleasantly, professionally, reaching critical mass.

I suppose there have always been rumblings in medicine, but somehow, the rumblings seem louder than usual. The promises of more with less is taking it’s toll. There are fewer perks these days for the work and risks involved for doctors. No one seems concerned, really, about liability reform. No one cares about doctor pay, except that it’s too much. Even the physician cheerleaders for the current reform efforts look tired. It’s hard to alter the course of a ship guided by business interests steeped in tradition, I guess.

This week doctors saw residents recalled to fill staffing shortages in a large, new teaching facility across town. Doctors there, it seems, were an afterthought. Residency work-hour restrictions prevent the remaining residents from filling the void left by their colleagues. So the extra workload necessarily falls on those who are ultimately responsible and already at risk for untoward outcomes: the already-busy attending physicians. Residents see it in their exhausted attending's eyes. Nothing is said, but the undercurrent is palpable. You see starry-eyed hospital administrators hell-bent on growth don’t fill those voids, doctors do.

Add to this, doctors read how another insurer has decided to change how they will pay doctors. At least that's how the headline read. But insurers don't pay doctors anymore, they pay their employers. How doctors are paid no longer relies on fee for service - that was gone long ago. But the public is told that the fee-for-service is what is broken. But doctors know what's broken are the incentives to maintain the middlemen that course through every layer of health care delivery that exists today in medicine. And God forbid there be more than a cursory mention of defensive medicine's toll. So the cash cow continues: policy-makers have decided that checking boxes on a computer screen or magically limiting readmissions is how "doctors" are to be paid. As if doctors can look in a crystal ball or should be expected plan for every contingency or every personal decision a patient might make or forget to make. Clearly these policy wonks ever heard of the People of Walmart. You see, for them, it's all about what they perceive is quality, remember, and quality involves a computer these days, not to mention maintaining shareholder value. So while insurers continue to cut payments to doctors and you can't get an appointment, remember: that's "quality" working for you.

Oh, and did I mention there’s a hiring freeze right now?

More tremors.

Can you feel them?

-Wes

Never before has there been more information at our disposal, yet more confusion. Like molecules being heated, the Brownian motion happening in medicine seems completely ineffectual for those of us on the front lines of care, geared more toward expensive facades than substance.

For the most part, doctors keep their heads down. Most of us are busy caring for patients, pushing to get home at least once each week before dinner. Most are humble servants to their patients, working tirelessly for their benefit. Sure, there are a few doctors participating in policy or medical associations, but it's clear to the rank and file that their leadership has already cashed out from patient care and are no longer participants in what medicine has become today. Worse: they’re too few in number and too underfunded and occassionally displayed as hood ornaments to validate a central policy decision.

Then there's call. No one likes call, but it must be covered. Doctors understand that medicine is 24/7/365 affair. But there's more people now, more places, and yes, more call. The burden falls on the doctors, so the tremors resonate louder. No large ones, mind you. But they're happening. Doctors are pleasantly, professionally, reaching critical mass.

I suppose there have always been rumblings in medicine, but somehow, the rumblings seem louder than usual. The promises of more with less is taking it’s toll. There are fewer perks these days for the work and risks involved for doctors. No one seems concerned, really, about liability reform. No one cares about doctor pay, except that it’s too much. Even the physician cheerleaders for the current reform efforts look tired. It’s hard to alter the course of a ship guided by business interests steeped in tradition, I guess.

This week doctors saw residents recalled to fill staffing shortages in a large, new teaching facility across town. Doctors there, it seems, were an afterthought. Residency work-hour restrictions prevent the remaining residents from filling the void left by their colleagues. So the extra workload necessarily falls on those who are ultimately responsible and already at risk for untoward outcomes: the already-busy attending physicians. Residents see it in their exhausted attending's eyes. Nothing is said, but the undercurrent is palpable. You see starry-eyed hospital administrators hell-bent on growth don’t fill those voids, doctors do.

Add to this, doctors read how another insurer has decided to change how they will pay doctors. At least that's how the headline read. But insurers don't pay doctors anymore, they pay their employers. How doctors are paid no longer relies on fee for service - that was gone long ago. But the public is told that the fee-for-service is what is broken. But doctors know what's broken are the incentives to maintain the middlemen that course through every layer of health care delivery that exists today in medicine. And God forbid there be more than a cursory mention of defensive medicine's toll. So the cash cow continues: policy-makers have decided that checking boxes on a computer screen or magically limiting readmissions is how "doctors" are to be paid. As if doctors can look in a crystal ball or should be expected plan for every contingency or every personal decision a patient might make or forget to make. Clearly these policy wonks ever heard of the People of Walmart. You see, for them, it's all about what they perceive is quality, remember, and quality involves a computer these days, not to mention maintaining shareholder value. So while insurers continue to cut payments to doctors and you can't get an appointment, remember: that's "quality" working for you.

Oh, and did I mention there’s a hiring freeze right now?

More tremors.

Can you feel them?

-Wes

Thursday, February 09, 2012

You Know You Love Your Work When

... you work in pathology and sport this cool tattoo (as seen in the lunch line today):

Nice!

-Wes

Other tattoos mentioned here:

Anatomical heart tattoos

Another Cool ICD Tattoo

Heart Curves

Taking Matters Into Your Own Hands

Click to enlarge

Nice!

-Wes

Other tattoos mentioned here:

Anatomical heart tattoos

Another Cool ICD Tattoo

Heart Curves

Taking Matters Into Your Own Hands

Wednesday, February 08, 2012

Our Conflicted Conflicts

This week's Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published a lengthy conflict of interest correction by Eugene Braunwald, editor of one of our iconic textbooks of cardiology and author of over 1000 peer-reviewed cardiovascular publications:

In reply to the correction, JAMA itself realizes it, too, has erred:

In my view, these doctor-pharma relationships are part of the reason there have been the many advances we have enjoyed in medicine. Without these dollars to academics and their programs, there would be no research programs and little to no innovation. There simply is not enough dollars to support the costs of doing the work from independent sources, especially in today's highly regulated research environment. Companies vested in bringing a new drug to market MUST do clinical trials to prove their safety and efficacy before their drugs are sold in the US. So companies bring their trials to well-respected doctors who see the proper patients. In turn, these doctors present the protocols to their Institutional Review Boards, process the reams of paperwork, ultimately decide which patient(s) might be appropriate candidates for the new medication, prescribe the drug, watch (and record) it's side effects and benefits, treat complications (if they occur), collect and analyze the data (often with research technicians and nurses who help with blood tests and data collection), and publish the papers with the results. And yes, they collect a paycheck each month.

It's what MUST happen to approve ANY drug.

So why all the fuss about a prominant academic cardiologist updating his conflicts in this "gotcha" moment of revelation?

I think in part it's because our drugs (and health care in general) has gotten so expensive. Seriously, if innovative chemotherapeutic drug regimens weren't going into the tens of thousands of dollars (in some cases), we (as the consumers of these drugs) probably woundn't care. But when we see the costs of these new drugs impact to our health insurance premiums and wallets directly, we look for people to blame.

And doctors, the intermediaries between the pharmaceutical companies and patients, are the easy target, especially when so many research doctors later morph into highly-paid marketing spokespersons once the research drug is approved for sale.

Doctors are starting to understand this. But like "The Boy Who Cried Wolf," we now see doctors disclosing everything to everybody so often that few are listening anymore. Disclosure slides are lucky to last a tenth of a second before a talk and most doctors don't mind.

That's because doctors know these "conflicts" inherent to our research process have not changed, because any research takes money - TONS of money. But now, instead of money being given to the doctor and his research program, it goes to "independent" research "institutes" or "foundations" designed to mix their donations with funds from private philanthropic support so the same dollar support is harder to track and gains favor with government regulators. All perfectly legal. All much more expensive. Yet most of it the same.

That's because, believe it or not, when it works, sometimes the collaboration between doctor-researcher and industry can actually become a net positive for all of us.

-Wes

h/t Retraction Watch

To the Editor: It has been brought to my attention that there were differences in my financial disclosures in a number of articles recently published in JAMA, and this warrants explanation.Dr. Braunwald explains the varous relationships inherent to discussing virtually any drug in our cardiovascular armamentatium. I encourage you to read the full text.

In reply to the correction, JAMA itself realizes it, too, has erred:

We appreciate Dr Braunwald providing his professional and transparent explanation to clarify the differences in the reported financial disclosures among several of his recent publications in JAMA. We fully recognize that determining relevant financial relationships involves judgment and that reporting of financial disclosure information certainly is not an exact science. In fact, in one of the Commentaries(1) that Dr Braunwald mentions, his co-author, Dr Gheorghiade, had reported to JAMA that he had received consulting fees from Bayer, Novartis, Sigma Tau, Johnson & Johnson, Takeda, Otsuka, and Medtronic. However, these disclosures inadvertently were omitted from the published article. The editors apologize for this oversight and regret this error.With the depth and breadth of pharmaceutical and medical device company funding of academe, journals, and doctors is so pervasive and the disclosures so inclusive, what are readers to think?

In my view, these doctor-pharma relationships are part of the reason there have been the many advances we have enjoyed in medicine. Without these dollars to academics and their programs, there would be no research programs and little to no innovation. There simply is not enough dollars to support the costs of doing the work from independent sources, especially in today's highly regulated research environment. Companies vested in bringing a new drug to market MUST do clinical trials to prove their safety and efficacy before their drugs are sold in the US. So companies bring their trials to well-respected doctors who see the proper patients. In turn, these doctors present the protocols to their Institutional Review Boards, process the reams of paperwork, ultimately decide which patient(s) might be appropriate candidates for the new medication, prescribe the drug, watch (and record) it's side effects and benefits, treat complications (if they occur), collect and analyze the data (often with research technicians and nurses who help with blood tests and data collection), and publish the papers with the results. And yes, they collect a paycheck each month.

It's what MUST happen to approve ANY drug.

So why all the fuss about a prominant academic cardiologist updating his conflicts in this "gotcha" moment of revelation?

I think in part it's because our drugs (and health care in general) has gotten so expensive. Seriously, if innovative chemotherapeutic drug regimens weren't going into the tens of thousands of dollars (in some cases), we (as the consumers of these drugs) probably woundn't care. But when we see the costs of these new drugs impact to our health insurance premiums and wallets directly, we look for people to blame.

And doctors, the intermediaries between the pharmaceutical companies and patients, are the easy target, especially when so many research doctors later morph into highly-paid marketing spokespersons once the research drug is approved for sale.

Doctors are starting to understand this. But like "The Boy Who Cried Wolf," we now see doctors disclosing everything to everybody so often that few are listening anymore. Disclosure slides are lucky to last a tenth of a second before a talk and most doctors don't mind.

That's because doctors know these "conflicts" inherent to our research process have not changed, because any research takes money - TONS of money. But now, instead of money being given to the doctor and his research program, it goes to "independent" research "institutes" or "foundations" designed to mix their donations with funds from private philanthropic support so the same dollar support is harder to track and gains favor with government regulators. All perfectly legal. All much more expensive. Yet most of it the same.

That's because, believe it or not, when it works, sometimes the collaboration between doctor-researcher and industry can actually become a net positive for all of us.

-Wes

h/t Retraction Watch

Tuesday, February 07, 2012

Monday, February 06, 2012

The Politics of Measuring Outcomes

It's February, and with February comes Valentine's Day, and with Valentine's Day, comes Heart Month, and with Heart Month, comes the department of Health and Human Services press release promising a million lives saved if we just eat right, stop smoking, and have our free blood pressure and cholesterol checks. We are told this bold new initiative will be working to save a million lives. After all, "$1 of every $6 in health care" is spent on heart disease.

But how, exactly, are we going to measure our outcomes with any of these initiatives? Will our feel-good press releases make it so? Do we really have a good system of determining the cause of death now versus several years from now to measure the impact of these programs? Are we really measuring how much it costs to screen all these people versus how much money we save?

Of course not. That would be a scientific approach.

Today we are seeing medicine increasingly managed through politics and empty promises. As doctors interested in saving lives, we would LOVE to see the impact of these simple measures first hand, but we rarely do. Only after ten or twenty years can we see the sudden lengthening of mortality curves from smoking cessation, for instance. Yet smoking, even with it's well-publicized detrimental health effects, is still widely practiced by our teenagers and young adults. More importantly from a cost standpoint (our real problem, right?), even if these prevention programs are effective, longer lives mean more costs spent per person on health care over people's lifetime, not less.

So while I appreciate the government's call for preventative measures in heart disease as a way to save a million lives and save money, we should ask ourselves as money is stripped from government health care in the future, on whom will the health care axe be falling? Sadly, it's likely to be the very people who need the most health care services in the first place: the elderly.

Hospitals and doctors are working hard to cut the fat from our health care spending. Never before has there been such scrutiny on the health care system to save money. Large systems of care provision are being developed to economize and streamline care delivery in an effort to do more with less. But the inevitable cuts to spending on health care promised by the government in the next several years is lost on none of us tasked with the day-to-day responsibility of caring for people in such a setting. As staff are continually pruned and work-hours extended, rest assured there be a flipside to the rosy prevention promises made by our government as cuts to health care funding take effect.

Yet somehow, no one seems interested in measuring the impact these long-term changes will have on our older, sicker patients or on those who care for them.

You see, that wouldn't be good for politics.

-Wes

But how, exactly, are we going to measure our outcomes with any of these initiatives? Will our feel-good press releases make it so? Do we really have a good system of determining the cause of death now versus several years from now to measure the impact of these programs? Are we really measuring how much it costs to screen all these people versus how much money we save?

Of course not. That would be a scientific approach.

Today we are seeing medicine increasingly managed through politics and empty promises. As doctors interested in saving lives, we would LOVE to see the impact of these simple measures first hand, but we rarely do. Only after ten or twenty years can we see the sudden lengthening of mortality curves from smoking cessation, for instance. Yet smoking, even with it's well-publicized detrimental health effects, is still widely practiced by our teenagers and young adults. More importantly from a cost standpoint (our real problem, right?), even if these prevention programs are effective, longer lives mean more costs spent per person on health care over people's lifetime, not less.

So while I appreciate the government's call for preventative measures in heart disease as a way to save a million lives and save money, we should ask ourselves as money is stripped from government health care in the future, on whom will the health care axe be falling? Sadly, it's likely to be the very people who need the most health care services in the first place: the elderly.

Hospitals and doctors are working hard to cut the fat from our health care spending. Never before has there been such scrutiny on the health care system to save money. Large systems of care provision are being developed to economize and streamline care delivery in an effort to do more with less. But the inevitable cuts to spending on health care promised by the government in the next several years is lost on none of us tasked with the day-to-day responsibility of caring for people in such a setting. As staff are continually pruned and work-hours extended, rest assured there be a flipside to the rosy prevention promises made by our government as cuts to health care funding take effect.

Yet somehow, no one seems interested in measuring the impact these long-term changes will have on our older, sicker patients or on those who care for them.

You see, that wouldn't be good for politics.

-Wes

Thursday, February 02, 2012

Tomorrow is National Wear Red Day!

It's all about heart disease for the month of February and to commemorate the occassion the American Heart Association has designated tomorrow as "National Wear Red Day!"

As most of you know, I LOVE "Go Red" day and all its' marketing glitz that targets women (never mind that more men die of heart disease than women). It's not easy to find a politically-correct cause to piggy-back upon to sell more soups, Seiko watches and candles.

But I'm still behind the effort. Really I am. And so, once again in support of this important event, I'll be wearing red...

Rock on!

-Wes

As most of you know, I LOVE "Go Red" day and all its' marketing glitz that targets women (never mind that more men die of heart disease than women). It's not easy to find a politically-correct cause to piggy-back upon to sell more soups, Seiko watches and candles.

But I'm still behind the effort. Really I am. And so, once again in support of this important event, I'll be wearing red...

Rock on!

-Wes

Wednesday, February 01, 2012

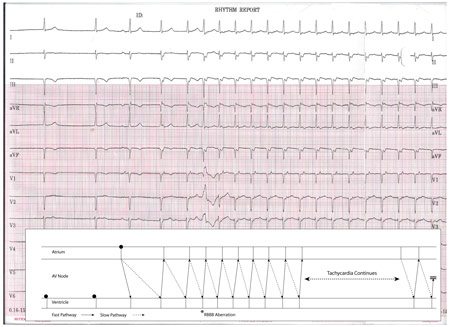

EKG Du Jour #25 - The Exercise Enthusiast - Explained

Sorry about the delay, but unlike most of the EKG Du Jour series of EKG's, I elected to make a separate post to explain the interesting tracings that first appeared here.

As a refresher, the original 12-lead rhythm strip obtained on this healthy, asymptomatic individual looked like this when he presented for evaluation of two near syncopal spells:

The third beat is where things get interesting. Here, a P wave is clearly seen that conducts to the ventricle with a normal PR interval. What is unsual, however, is the finding that the fourth beat (that appears to be junctional) occurs earlier than one would expect than a junctional escape beat to occur (based on the earlier two junctional beats). In effect, this fourth beat appears "pulled in" earlier to the preceding beat, but also has a clearly visible retrogradely-conducted P wave (best seen in V1) that occurs immediately after the QRS complex. At this point, the patient is in a supraventricular tachycardia that accelerates slightly with the fifth beat occurring earlier - probably because of hemodynamic alterations that occur due to the unusual cardiac activation sequence (slightly decreased BP and increased catecholamine level).

The sixth beat is a widened QRS complex of RBBB morphology. This beat is either a PVC (less likely) or (more likely) an aberrantly-conducted supraventricular beat. This beat aberrates because of the long-short nature of the initiation of the tachycardia that finds the right bundle branch refractory while the left bundle branch conducts to the ventricle. With continued tachycardia, the right bundle branch recovers and the tachycardia continues with a narrow QRS morphology.

The very last beat of the tracing defines the end of the run of supraventricular tachycardia.

So how did the tachycardia initiate?

This is an example of a normal P wave initiating SVT due to AV nodal "double-fire." That is, a single atrial beat conducts down BOTH the fast and slow pathway of the AV node. In this case, typical AV nodal reentrant tachycardia was initiated by a single sinus beat in this gentleman.

Here is the above tracing explained using a favorite of EP's -- a ladder diagram:

-Wes

As a refresher, the original 12-lead rhythm strip obtained on this healthy, asymptomatic individual looked like this when he presented for evaluation of two near syncopal spells:

Click image to enlarge

The third beat is where things get interesting. Here, a P wave is clearly seen that conducts to the ventricle with a normal PR interval. What is unsual, however, is the finding that the fourth beat (that appears to be junctional) occurs earlier than one would expect than a junctional escape beat to occur (based on the earlier two junctional beats). In effect, this fourth beat appears "pulled in" earlier to the preceding beat, but also has a clearly visible retrogradely-conducted P wave (best seen in V1) that occurs immediately after the QRS complex. At this point, the patient is in a supraventricular tachycardia that accelerates slightly with the fifth beat occurring earlier - probably because of hemodynamic alterations that occur due to the unusual cardiac activation sequence (slightly decreased BP and increased catecholamine level).

The sixth beat is a widened QRS complex of RBBB morphology. This beat is either a PVC (less likely) or (more likely) an aberrantly-conducted supraventricular beat. This beat aberrates because of the long-short nature of the initiation of the tachycardia that finds the right bundle branch refractory while the left bundle branch conducts to the ventricle. With continued tachycardia, the right bundle branch recovers and the tachycardia continues with a narrow QRS morphology.

The very last beat of the tracing defines the end of the run of supraventricular tachycardia.

So how did the tachycardia initiate?

This is an example of a normal P wave initiating SVT due to AV nodal "double-fire." That is, a single atrial beat conducts down BOTH the fast and slow pathway of the AV node. In this case, typical AV nodal reentrant tachycardia was initiated by a single sinus beat in this gentleman.

Here is the above tracing explained using a favorite of EP's -- a ladder diagram:

Click image to enlarge

-Wes

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)