Why is it, with all the billions of dollars poured into health care information technology, that doctors can't query the information they hammer in to the computers themselves directly? Is it because our hospital administrators are scared of what we might find?

I am constantly amazed that I can't even query my work volume statistics. Despite the thousands of diagnosis and procedural codes that I have to enter on a computer to get paid, I'm not allowed to find out how many pacemakers I've performed for sick sinus syndrome versus complete heart block. I can't determine how many atrial fibrillation ablations I did last month without asking an administrator to "pull the data" for me.

Medicare gets the data.

The billers get the data.

Why can't I?

Should patient care information be valued less than billing data?

Don't get me wrong, there are plenty of good things that highly integrated electronic records can do for patient care, but seeing that doctors are the ones providing the care, shouldn't we be able to query, without restriction, any and all fields available pertaining to patient care? If I can program an Excel spreadsheet on my laptop to perform a nearly infinite number of queries, whay can't our billion-dollar electronic medical record companies make it just as easy for those providing the care to do the same?

Who knows, maybe we'll be able to find some improvements as a result.

Or might the potential that we find that all those information technology jobs are inefficient just too threatening to those in charge?

-Wes

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Collateral Damage

He had worked for years for that hospital - a faithful technician in a busy laboratory. He had grown up in the country, married, had two kids. The rolling meadows, farmland and tree-lined creeks were what he knew. He had a sense of commitment to this community and joined their fire department and trained to become an Emergency Medical Technician.

As the kids grew, so did their financial demands. An opportunity arose for him to become a technician at a cath lab ninety minutes away, so he lept. Years passed and he grew to become a reliable, capable member of the cath lab team who took call like everyone else.

Unfortunately, the economy sank and so did the value of his home. He lived in a rural area, so selling and buying closer to work was economically impossible. "Golden handcuffs" they call them. He'd have to commute to make it work.

He managed to make it work until the day a new policy arose: the 90-minute door-to-balloon time. Hospital policies were changed. It was the rage. Technicians now had to be available to the hospital within thirty minutes. "Quality care," they called it.

But the logistics would prove overwhelming for him.

At first he tried to rent a room close by when he was on call. When he was called, he could clear expenses. After all, call hours paid more then regular hours. But the calls were unreliable and this proved too expensive. Another option would have to be considered.

He tried sleeping in his car. At least he was close by and the accommodations affordable, but sleep was difficult. He dreaded those call nights. Call was difficult, work a challenge. In the end, it was untenable for him and his employer.

And the inevitable unintended consequence of a central policy may have saved some, but at the expense of another.

And like Paul Harvey used to say, "Now you know the rest of the story."

-Wes

As the kids grew, so did their financial demands. An opportunity arose for him to become a technician at a cath lab ninety minutes away, so he lept. Years passed and he grew to become a reliable, capable member of the cath lab team who took call like everyone else.

Unfortunately, the economy sank and so did the value of his home. He lived in a rural area, so selling and buying closer to work was economically impossible. "Golden handcuffs" they call them. He'd have to commute to make it work.

He managed to make it work until the day a new policy arose: the 90-minute door-to-balloon time. Hospital policies were changed. It was the rage. Technicians now had to be available to the hospital within thirty minutes. "Quality care," they called it.

But the logistics would prove overwhelming for him.

At first he tried to rent a room close by when he was on call. When he was called, he could clear expenses. After all, call hours paid more then regular hours. But the calls were unreliable and this proved too expensive. Another option would have to be considered.

He tried sleeping in his car. At least he was close by and the accommodations affordable, but sleep was difficult. He dreaded those call nights. Call was difficult, work a challenge. In the end, it was untenable for him and his employer.

And the inevitable unintended consequence of a central policy may have saved some, but at the expense of another.

And like Paul Harvey used to say, "Now you know the rest of the story."

-Wes

Monday, August 29, 2011

Cardiology Hospitalist Programs Becoming a Reality

From St. Louis Today:

The path to "cardiology proceduralist" continues.

-Wes

The first cardiology hospitalist program in the St. Louis area recently began at St. John’s Mercy Heart and Vascular Hospital allowing more focused care for hospitalized heart patients by board-certified cardiologists available throughout the day.On-site interventional "cardiology hospitalists" may improve door-to-balloon times during acute heart attacks, but will also place additional pressure on community-based interventional cardiologists to join forces with hospitals since their ability to expand their practices with new acute patients will be severely limited as a result.

Patricia Cole, MD, an interventional cardiologist, is the director of inpatient cardiology services at St. John’s Mercy leading the new group. Mary Carolyn Gamache, MD, FACC, recently joined Mercy as the second cardiology hospitalist. She has been practicing with Metro Heart Group of St. Louis since 1995. Along with the cardiologists, three nurse practioners will also be a constant presence for patients and families.

The path to "cardiology proceduralist" continues.

-Wes

Apixaban: Hailing Warfarin's Demise?

With the publication of "Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation" (the ARISTOLE trial) in the New England Journal of Medicine, the third drug in a series of medications designed to attack thrombin in the clotting cascade. The study was announced with quite a fanfare in Europe as cardiologists, financial analysts and reporters gushed forth with 'mega-blockbuster' praise this past weekend.

And for good reason.

This is the first trial to conclude that this direct Factor Xa inhibitor demonstrated a mortality superiority over warfarin when treating patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation (Two earlier trials showed a trend that way, but only reached mortality equivalency, not superiority: the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigratran's Re-LY Trial and rival direct Factor Xa inbibitor rivaroxaban's ROCKET-AF trial). Specifically, the 18,201-patient ARTISTOLE trial showed

So is warfarin now passé in the treatment of non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation?

Not quite yet.

There remain some significant caveats for doctors and patients that should be remembered now that these advantages to apixaban have been published.

-Wes

And for good reason.

This is the first trial to conclude that this direct Factor Xa inhibitor demonstrated a mortality superiority over warfarin when treating patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation (Two earlier trials showed a trend that way, but only reached mortality equivalency, not superiority: the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigratran's Re-LY Trial and rival direct Factor Xa inbibitor rivaroxaban's ROCKET-AF trial). Specifically, the 18,201-patient ARTISTOLE trial showed

The rate of the primary outcome (major bleeding) was 1.27% per year in the apixaban group, as compared with 1.60% per year in the warfarin group (hazard ratio with apixaban, 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66 to 0.95; P<0.001 for noninferiority; P=0.01 for superiority). The rate of major bleeding was 2.13% per year in the apixaban group, as compared with 3.09% per year in the warfarin group (hazard ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.80; P<0.001), and the rates of death from any cause were 3.52% and 3.94%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.99; P=0.047). The rate of hemorrhagic stroke was 0.24% per year in the apixaban group, as compared with 0.47% per year in the warfarin group (hazard ratio, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.75; P<0.001), and the rate of ischemic or uncertain type of stroke was 0.97% per year in the apixaban group and 1.05% per year in the warfarin group (hazard ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.13; P=0.42).(Although registration is required, please see the excellent review by Larry Husten over at the Cardioexchange blog).

So is warfarin now passé in the treatment of non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation?

Not quite yet.

There remain some significant caveats for doctors and patients that should be remembered now that these advantages to apixaban have been published.

- While aspirin was used in about 30% of the patients placed on apixaban in this study, only 1.9% of the patients were also taking the common antiplatelet agent clopidogrel. Recall that the study protocol stated "Patients taking a thienopyridine at baseline were not eligible for inclusion in the study, although these drugs could be prescribed during the study if an indication emerged." The risks for bleeding for patients already on aspirin and clopidogrel (or its more potent cousin prasugrel) may be significant. Certainly the lack of antidote to the anticoagulating effect of this medication may make this "trifecta" of anticoagulants particularly hazardous as long as an antidote to this new class of thrombin-inhibiting drugs does not exist.

- It is important to remember that patients with prosthetic valves were not included in any of the Factor Xa/thrombin inhibitor studies. Warfarin will still be required for those patients - at least until proof of their safety in this cohort of patients surfaces.

- As with dabigatran that has shown some challenges with its limited available dosages in the elderly, clinical experience will dictate whether a drug with a "one dose fits all" like apixaban is as safe as touted. Also, we can only hope that we don't find little "storage and handling issues" for apixaban after release like we did for dabigatran.

- Finally, we are yet to discover apixaban's price (soon to be marketed under the brand name of Eliquis®). Cost remains a significant consideration for patients wanting to make the switch to these newer thrombin-inhibiting medications. With greater cost-shifting for health care and medications being placed on patients, patients with limited monthly budgets will still be slow to switch to these agents.

-Wes

Sunday, August 28, 2011

The Interrupters

'The Interrupters' tells the stories of three Violence Interrupters who try to protect their communities from the violence they once employed. Shot over the course of a year out of Kartemquin Films, 'The Interrupters' captures a period in Chicago when it became a national symbol for violence in America. During that time, the city was besieged by high-profile incidents, most notably the brutal beating of Derrion Albert, a Chicago High School student, whose death was caught on videotape.

This is where I'll be tonight. I'd encourage all my readers to see this movie if it comes to your town because people can make a difference. You can read more about the movie here and where the screenings are being held here.

-Wes

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Friday, August 26, 2011

Millionaire Matchmaker

"Oh my goodness, you have to come watch this!"

I have no idea what inspired my wife to channel-surf and find the show Millionaire Matchmaker on TV, but there it was: relationship candy for a psychologist. What can I say? It was another Big Night at home after a long day's work: we sat, we laughed, we decompressed.

Until 10:38 pm when the beeper sounded.

"Awww. Don't you want to see how it ends?" she asked. I felt like I wouldn't be missing much and as it turns out, it was the ER. "Heart rate 26," they told me.

"Wide or narrow QRS?" I asked.

"Wide"

"Meds?"

They listed them.

"Potassium?"

"Not back yet."

They explained the situation further. It wasn't much of a decision, I had to go in.

"I'm so sorry," she said from the couch looking back.

It was a bit of a drive on a nice summer night. While tired, I still noticed the feeling of anticipation that comes with such a call. "I can still function," I thought. And so the night progressed:

11:00 pm - Arrived, potassium 6.4, creat 2.0 "Has he gotten the glucose and insulin?"

11:45 pm - Not much change in rhythm. Pressure stable. Vomiting. "Patience," I thought. Better call the team in for a pacer.

12:00 midnight - Consent signed, family witnessed.

12:15 am - To lab

12:45 am - Temp wire in.

01:00 am - Start the pacer. Access challenging, but accomplished. Pt moaning, more alert, wants more information. "You're in surgery, sir. I need you to hold still!"

01:30 am - RV lead in. Atrial lead started.

2:00 am - after considerable struggle, area of atrium that is willing to pace is identified and lead placed succesfully. P waves? What P waves?

2:45 am - Pocket closed, pt moved to post-op holding area. Met family, charted, orders written.

2:58 am - head home. Police stop to ask why I was doing 7 mph over limit. Explain my night. They get it. ID checked. "Drive carefully doctor."

3:20 am - Arrive home. "I'm too old for this."

3:28 am - "So let me tell you what happened to the OCD guy... and that narcissist multi-millionaire? Oh. My. Goodness! On and on she went, describing the scenarios that had occurred earlier as my head hit the pillow, her voice growing softer...

Maybe it's all the years together we've learned to cope with these disruptions. Still, I'm grateful we can still pick up right where we've left off, especially when such important plot summaries have occurred.

-Wes

I have no idea what inspired my wife to channel-surf and find the show Millionaire Matchmaker on TV, but there it was: relationship candy for a psychologist. What can I say? It was another Big Night at home after a long day's work: we sat, we laughed, we decompressed.

Until 10:38 pm when the beeper sounded.

"Awww. Don't you want to see how it ends?" she asked. I felt like I wouldn't be missing much and as it turns out, it was the ER. "Heart rate 26," they told me.

"Wide or narrow QRS?" I asked.

"Wide"

"Meds?"

They listed them.

"Potassium?"

"Not back yet."

They explained the situation further. It wasn't much of a decision, I had to go in.

"I'm so sorry," she said from the couch looking back.

It was a bit of a drive on a nice summer night. While tired, I still noticed the feeling of anticipation that comes with such a call. "I can still function," I thought. And so the night progressed:

11:00 pm - Arrived, potassium 6.4, creat 2.0 "Has he gotten the glucose and insulin?"

11:45 pm - Not much change in rhythm. Pressure stable. Vomiting. "Patience," I thought. Better call the team in for a pacer.

12:00 midnight - Consent signed, family witnessed.

12:15 am - To lab

12:45 am - Temp wire in.

01:00 am - Start the pacer. Access challenging, but accomplished. Pt moaning, more alert, wants more information. "You're in surgery, sir. I need you to hold still!"

01:30 am - RV lead in. Atrial lead started.

2:00 am - after considerable struggle, area of atrium that is willing to pace is identified and lead placed succesfully. P waves? What P waves?

2:45 am - Pocket closed, pt moved to post-op holding area. Met family, charted, orders written.

2:58 am - head home. Police stop to ask why I was doing 7 mph over limit. Explain my night. They get it. ID checked. "Drive carefully doctor."

3:20 am - Arrive home. "I'm too old for this."

3:28 am - "So let me tell you what happened to the OCD guy... and that narcissist multi-millionaire? Oh. My. Goodness! On and on she went, describing the scenarios that had occurred earlier as my head hit the pillow, her voice growing softer...

Maybe it's all the years together we've learned to cope with these disruptions. Still, I'm grateful we can still pick up right where we've left off, especially when such important plot summaries have occurred.

-Wes

Thursday, August 25, 2011

On Medicare's Wearable Cardiac Defibrillator "Reconsideration"

I know what you're thinking. "Did he fire six shots or only five?" Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement I kind of lost track myself. But being as this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world, and would blow your head clean off, you've got to ask yourself one question: Do I feel lucky?

Well, do ya, punk?

Harry Callihan, from the movie Dirty Harry

It was a small article in the Wall Street Journal on 8 August 2011: "Zoll Medical Falls As LifeVest May Face Reimbursement Revisions." No doubt most doctors missed this, but the implications of this article for our patients discovered to have weak heart muscles and considered at high risk for sudden cardiac death could be profound.

That's because Medicare (CMS) is considering the requirement for the same waiting period after diagnosis of a cardiomyopathy or myocardial infarction as that for permanent implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs). To this end, they issued a draft document that contains the new proposal for their use.

By way of background, Zoll Medical makes the only wearable external cardiac defibrillator on the market, marketed as "LifeVest." The device is fairly simple: it consists of (1) a vest-like wearable garmet that contains EKG electrodes to sense a person's heart rhythm and and front and back electrode pads to deliver shock therapy and (2) a monitoring computer that can respond to the development of potentially left-threatening rhythm problems by automatically rupturing hidden gel-packs under the electrode pads before delivering a defibrillation shock to the patient to restore normal rhythm. Clinically, heart rhythm specialists have used these devices to assure our patients are protected from the development of life-threatening heart rhythm disorders as they begin medical therapy for their condition. After three months of medical therapy (according to our guidelines) if a person's heart muscle does not improve sufficiently, they are candidates for surgical implantation of a permanent (internal) cardiac defibrillator to protect against sudden cardiac arrest. For Medicare-eligible patients in need of these devices, they must pay a $200/month co-pay for their rental and the company receives approximately $2641 per month from Medicare. Certainly the use of these devices is not cheap, but they are much less expensive than the cost of an implantable defibrillator.

CMS justifies their need to "reconsider" their prior approval of wearable defibrillators on the basis of five documents that do not pertain to wearable cardiac defibrillators at all:

1.Epstein AE, et.al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;51(21);e-1-62The use of the wearable cardiac defibrillator has dramatically increased after Department of Justice investigations surfaced regarding the appropriateness of defibrillator implantations being performed. Doctors looked to these devices as an acceptable compromise to the governmental and evidenced-based studies that suggested no signficant early mortality benefit with devices early after MI.

2.Hohnloser, SH, et.al. Prophylactic Use of an Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator after Acute Myocardial Infarction (DINAMIT-Defibrillator in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial). N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2481-88

3.Bigger JT, et.al. Prophylactic Use of Implanted Cardiac Defibrillators in Patients at High Risk for Ventricular Arrythmias after Coronary-Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;337:1569-75

4.Bardy GH, et.al. Home Use of Automated External Defibrillators for Sudden Cardiac Arrest. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358 (online publication only at www.nejm.org)

5.Steinbeck G, et.al. Defibrillator Implantation Early after Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1427-36

But clinically, doctors remained concerned about their patients after a severe heart attack or when a very weak heart muscle is discovered. When making prospective decisions about their patient's care, theydoctors do not have the benefit of retrospectively reviewing a patient's outcome in such a precarious situation. They only see the pleading eyes, the young physique, the patient's children and the desire to live to see another day.

And not unexpectedly, wearable cardiac defibrillators have been effective at saving lives in these high risk patient populations. If these wearable cardiac defibrillators aren't approved for early protection, what will doctors be forced to do? There are three possibilities: (1) treat them medically and wish them the best of luck for the next several months, (2) require they remain admitted for as long as three months to assure their safety, or (3) tell the patient they'll have to pay if they want the protection.

So how are these payement decisions made by our government officials? Who makes them? I realized while writing this post that I was not familiar how Medicare decides how and if they should pay for such a life-saving therapy.

The answer lies with the insurers contracted by Medicare called "Durable Medical Equipment (DME) Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC)" or "DME MAC" for short. These are the same folks who decide if wheelchairs or home oxygen therapy is paid for. In the interest of transparency, I thought it would be interesting to expose exactly how, and by whom, the decision for wearable defibrillators will be made by currently. (It never hurts to keep the public informed who is deciding their fate clinically.)

First, it seems Medicare has contracted with four really important insurers which each manages a separate "region" of states called "jurisdictions:"

- Jurisdiction A - http://www.medicarenhic.com

- Jurisdiction B - http://www.ngsmedicare.com

- Jurisdiction C - http://www.cgsmedicare.com/jc

- Jurisdiction D - http://www.noridianmedicare.com/dme

Next, each of these jurisdictions has its own medical administrator with the

- Jurisdiction A: Paul Hughes, MD – FAMILY PRACTICE, with the National Heritage Insurance Co., Hingham, MA

- Jusrisdiction B: Stacey Brennan, MD – FAMILY PRACTICE with National Government Services, Indianapolis, IN Jurisdiction C: Robert Hoover, Jr, MD, MPH, FACP – INTERNAL MEDICINE with CIGNA Government Services, Nashville TN

- Jusdiction D: Richard Whitten, MD, MBA, FACP – INTERNAL MEDICINE, CRITICAL CARE with Noridian Administrative Services, LLC, Fargo, ND

Now even though this "reconsideration" request has submitted to all four jurisdictions, only one jurisdiction typically reviews a particular issue and the others usually follow the first reviewer's lead.

As part of this "reconsideration," a public hearing occurs. In the case of wearable defibrillators (which will be reviewed with suction pumps and pneumatic compression devices), the meeting will occur at the Sheraton Baltimore North Hotel in Baltimore, MD. Then, after the public hearing, a three week "open comment period occurs" where the public can offer their agreement or disagreement (and why) to the proposed draft recommendation by submitting comments to a specific e-mail: nhicdmedraftLCDfeedback@hp.com . Comments must be recieved by 23 Sep 2011. After that time, a decision is rendered regarding the appropriate circumstances (if any) these "durable medical goods" will be paid for.

Doctors interested in contributing their thoughts are welcome to. Just be respectful and link to data or studies, if possible. Realize that the lucky individuals are not cardiologists nor cardiac electrophysiologists. They are physicians working for insurers. The draft proposal for wearable defibrillators is not a final document and is subject to change.

It is interesting to ponder why non-cardiologists from the insurance industry have proposed this restriction with little data to prove their harm to patients while significant data suggesting benefit exists to this therapy. I suspect that doctors who use sophisticated medical devices are more likely to see these "reconsiderations" for payment by CMS in the years ahead even though, by policy, cost is not supposed to be a consideration for approvals.

Staying aware of the payment system in place and who makes these decisions going forward might become our best way to effectively advocate for our patients in the coming years.

-Wes

PS: Reponsible corrections to my understanding of this process are welcomed. After all, I'm just a doctor.

Monday, August 22, 2011

Infection Rates with Cardiac Devices: Increasing or New Norm?

A new report published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and reported in theHeart.org and elsewhere, suggests the infection rate of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CEID's) between 1993 and 2008 has greatly increased from 1.53% in 2004 to 2.41% in 2008 (p < 0.001) with a dramatic rise in 2005:

Of course:

Recall, too, that biventricular pacing had just come on the seen in 2002. The addition of the third pacing lead for biventricular pacing with pacing or defibrillator systems greatly increased the complexity and duration of device implant procedures. Early on, it was not uncommon for procedures to last twice or three times as long as earlier device implant procedures owing to the rudimentary lead delivery systems in place.

In addition, it would be very unlikely that the morbidity of the average hospital patient population suddenly changed significantly in 2005 compared to the earlier years studied. Was there a sudden run on respiratory and renal diseases that I was unaware of?

In conclusion, many other factors have played a role in the higher infection rates reported for implantable cardiac devices after 2005. I suspect conventional device implantation infection rates have not changed much. Instead, the combination of more complicated devices paired with better measurement of complication rates (and the requirement to do so) more likely explains the "rise" of the infection rates seen.

Still, it's helpful to review these data. But further analyses are warranted before implicating the increase in infection rate seen on only the co-morbidity measurements made from the weak data offered by computerized Medicare diagnosis codes.

Haven't we learned this by now?

-Wes

Reference:

16-Year Trends in the Infection Burden for Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators in the United States: 1993 to 2008 J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011; 58:1001-1006, doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.033

Click image to enlarge

The incidence of 4 major comorbidities (renal failure, respiratory failure, heart failure, and diabetes) in patients with CIED infection remained fairly constant from 1993 through 2004 when a marked increase was observed (Fig. 5). In addition, the risk of mortality significantly increased in patients with respiratory failure (odds ratio: 13.58; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 12.88 to 14.3), renal failure (odds ratio: 4.28; 95% CI: 4.04 to 4.53), heart failure (odds ratio: 2.71; 95% CI: 2.54 to 2.88) but decreased slightly in patients with diabetes (odds ratio: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.86 to 0.96) (p < 0.001).The authors also noted that ICD implant incidence increased from 12% to 35% of all implants over the 16-year period. But despite the increase in incidence of ICD implants and proposed patient morbidity, wasn't 2005 the same year a rash of ICD recalls and negative press occurred? Why didn't infection rates decrease in 2006-2008 when ICD implant rates fell? Might there have been another huge reason infection rates suddenly "increased?"

Of course:

In January 2005 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded the covered indications for primary prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) to incorporate the findings from the recently published Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) and the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT II). As part of this expansion, CMS mandated that a national registry be formed to compile data on Medicare patients implanted with primary prevention ICDs to confirm the appropriateness of ICD utilization in this patient population. Responding to this mandate, a collaborative effort of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), utilizing the expertise of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR®), developed Version 1 of the ICD Registry™. CMS selected the NCDR ICD Registry as the mandated national registry in October 2005 and enrollment opened on January 1, 2006.So more devices by more implanters, about a quarter of whom had a limited experience implanting these devices was occurring.

Recall, too, that biventricular pacing had just come on the seen in 2002. The addition of the third pacing lead for biventricular pacing with pacing or defibrillator systems greatly increased the complexity and duration of device implant procedures. Early on, it was not uncommon for procedures to last twice or three times as long as earlier device implant procedures owing to the rudimentary lead delivery systems in place.

In addition, it would be very unlikely that the morbidity of the average hospital patient population suddenly changed significantly in 2005 compared to the earlier years studied. Was there a sudden run on respiratory and renal diseases that I was unaware of?

In conclusion, many other factors have played a role in the higher infection rates reported for implantable cardiac devices after 2005. I suspect conventional device implantation infection rates have not changed much. Instead, the combination of more complicated devices paired with better measurement of complication rates (and the requirement to do so) more likely explains the "rise" of the infection rates seen.

Still, it's helpful to review these data. But further analyses are warranted before implicating the increase in infection rate seen on only the co-morbidity measurements made from the weak data offered by computerized Medicare diagnosis codes.

Haven't we learned this by now?

-Wes

Reference:

16-Year Trends in the Infection Burden for Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators in the United States: 1993 to 2008 J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011; 58:1001-1006, doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.033

Beware of Direct-Message Twitter Phishing

It was sent by direct message:

I've seen a few of these Twitter messages on my iPhone and they seem to be more prevalent recently. The link provided in these messages doesn't take you to a forum or a photo, but rather to an official Twitter-like front page where you have to enter your "Full name" and e-mail as part of the log-in process. It is, of course, an attempt to gather your personal information. But for reason I don't understand, the iPhone OS (a la Safari) does not recognize these malicious URL's, but Firefox and Chrome on a more conventional desktop does recognize these sites for what they are: malicious software attempting to obtain your personal information.

Doctors and other health care providers may not be aware of these scams...

... 'til now.

So beware, it's the internet out there, remember?

-Wes

References:

BEWARE Of Twitter Phishing DM –“Someone said this real bad thing about you in a blog”

Twitter warns vs new direct-message phishing scam.

Mashable: WARNING: New Twitter Phishing Scam Spreading Via Direct Message

@personyoufollow Thought you'd should know they're saying really, really bad things about you over here http://ts.****.co... or maybe this:

@personyoufollow Thought you'd like to see the photo I took of you... http://ts.****.co

I've seen a few of these Twitter messages on my iPhone and they seem to be more prevalent recently. The link provided in these messages doesn't take you to a forum or a photo, but rather to an official Twitter-like front page where you have to enter your "Full name" and e-mail as part of the log-in process. It is, of course, an attempt to gather your personal information. But for reason I don't understand, the iPhone OS (a la Safari) does not recognize these malicious URL's, but Firefox and Chrome on a more conventional desktop does recognize these sites for what they are: malicious software attempting to obtain your personal information.

Doctors and other health care providers may not be aware of these scams...

... 'til now.

So beware, it's the internet out there, remember?

-Wes

References:

BEWARE Of Twitter Phishing DM –“Someone said this real bad thing about you in a blog”

Twitter warns vs new direct-message phishing scam.

Mashable: WARNING: New Twitter Phishing Scam Spreading Via Direct Message

Knowing When to Quit CPR

... using capnography:

White says that before the use of capnography, the only way of assessing blood flow to vital organs was by feeling for a pulse or by looking for dilated pupils. He says those methods are very crude and can fail. Snitzer never had a pulse despite good carbon dioxide readings. Without the information from capnography, he says it would have been reasonable to stop CPR — and Snitzer would have likely died.-Wes

"The lesson that I certainly learn from this is you don't quit, you keep trying to stop that rhythm as long as you have objective, measurable evidence that the patient's brain is being protected by adequate blood flow as determined by the capnographic data," says White.

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Job Security

... from the World Famous Bacon Habit Cafe at the Illinois State Fair, Springfield, IL with a menu that offers beer-battered bacon, chocolate covered bacon, bacon-wrapped chicken strips and (I'm not making this up) "really mad turkey nads!"

-Wes

Click image to enlarge

-Wes

Saturday, August 20, 2011

'Twas the Week Before School Starts

(Republished with apologies to Clement Clarke Moore)

Came traveling families with SUV's crammed.

The book bills, the dorm tab, all paid with great care,

But one more time on probation and they'll no longer be there.

The teens were all snuggled, the back seats were beds.

We pulled on to campus, with hope but some dread.

We unloaded the duffles and bags with great care,

In hopes that we would not find beer stashed somewhere.

When out on the quad, came an unearthly whine,

As all texted each other, to say they were fine.

Away to my cell phone, we looked with concern,

But nary a message did we get in turn.

The piercings, the highlights, oh, how they glistened!

They checked out each other, while the parents just listened.

When what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a parent liason, saying "Nothing to fear."

And the smiling dean, so lively and quick,

Asking each family to please buy a brick.

More rapid than eagles, the roommates they came,

I never knew my offspring had garnered such fame.

I need curtains, more CD's, a lamp and a chair,

A new pillow, some snacks and that gel for my hair.

To the Target, the Best Buy, a sweep through the mall,

Then dash away, dash away, dash away all.

They promised to study, they promise more mail,

Daddy was stoic, and Mommy was pale.

They threw out an "I love you," gave a hug, hands were shook.

Then away they all flew, without one second look.

Then I heard them exclaim, as I drove out of sight,

"My parents are gone, tonight's party night!"

-Wes and Diane Fisher

Friday, August 19, 2011

EKG Du Jour #22: A Rare Classic

I offer this gem to the EKG enthusiasts out there to ponder. It's not every day we find a 12-lead EKG of this from a post-operative patient with an ischemic cardiomyopathy:

Click image to enlarge

On Closure

The chief complaint, the history and physical, the differential diagnosis, the proper testing, the treatment.

From Day 1, these are the pieces of medicine that are hammered in to young doctors' heads: the best way to treat this or that, the best drug, widget or gizmo, the latest advance. We learn which approach is better than the other, which treatment to apply when more conventional approaches can't be taken. Each of these steps are drilled over and over again in the hopes of crafting a strategy for each clinical scenario a doctor is likely to encounter. Yet while each of these steps that are learned are important in their own right, few of these steps are critical to doctors' sustainability in their profession.

Because after the treatment strategy or therapy is applied, there's another vital part of the medical care that is often under-appreciated for doctors and policy makers: the closure.

"Closure" is the time in medicine where we either revel in our success or squirm in our failure. It's where we must face the music - good or bad - with our patients. More often than not, it's the time for doctors that brings meaning to our efforts and the hours we work.

Closure can occur at different times for different doctors. For specialists (increasingly called "proceduralists" these days), closure usually occurs in the post-operative or post-procedure period. For primary care doctors, "closure" occurs during the follow-up visit after a prolonged hosptitalization or difficult illness. For both types of doctors, it's the chance to see the good they did or bad they did first-hand. It a time to validate their understanding of the patient's ailment and the caliber of their treatment plan. Importantly, it's not the end of the patient's ongoing care but rather, it's the conclusion to a particular chapter of their care. For doctors, it's the critical time we grow as professionals.

Yet sadly, these moments of closure are becoming rarer for both the patient and the doctor.

With doctors racing between facilities on productivity compensation plans who must perform more cases in less time and in more locations to offset declining payment rates, it's become harder both logistically and financially to justify excessive post-operative time with patients after their procedures. The money required to feed the our massive system of administrators, collectors, quality score counters, overheads and salaries demands a constant ever-growing source of funds, so doctors must keep moving.

To that end, specialist physicians have seen post-operative care routinely clumped together with the pre-procedure and intra-operative care as one big "encounter" that pays health systems only once. Increasingly to add "value" to health care dollars, policy makers are shifting the "risk" of caring for patients to the providers of that care. Insurers and policy makers like to call this shifting from "procedural-based" payments to "outcome-based" payments. In theory this sounds nice, but it's robbing the doctors of the closure time so critical in the valuation of their profession in favor of treating a greater quantity of healthier, lower-risk patients to assure reliable payments to the system.

For primary care doctors who now only see patients in their offices, the opporunity to see the product of a continuous care strategy has been surrendered to the hospitalist movement robbing them of closure time. And even the hospitalists who "diagnose and say 'adios'" from the confines of the hospital, the opportunity see the late consequences of their care in a non-critical environment has been lost to production quotas as well. No fractious group "medical home" care in the world can replace this loss of closure inflicted upon primary care and shift-working hospitalist physicians or the patients for whom they care.

Our health policy analysts have assured us these "closure" visits can be accomplished by ancillary care providers. Technically, they are correct. But there is no question that the loss of these post-procedure visits by the treating physician or operating surgeon robs them of a critically important opportunity for continuous self-improvement as they reflect on the quality and cailber of their work first-hand. Further, doctors lose an opportuntity after the haze of amnestic medications have subsided to educate and re-connect. Doctors need this time with their patients just like patients like this time with their doctors - maybe even more. It's what makes it worthwhile to get up and do it all again.

Despite the current push, I still try to see my patients after a procedure whenever possible. Sure, we don't get paid for this, but I still relish a patient's gentle smile or a quiet "thank you." More importantly, when things aren't perfect, I need the opportunity to reassure and console. If things really don't go well, I find there are huge benefits derived when I can explain and empathize with the patient's situation.

Still, I feel the tug. "It's not efficient," they tell me.

Perhaps.

But it's this closure that sustains me and I suspect sustains many in our profession. And honestly? If doctors' closure time continues to be parsed and devalued further, they'll look for validation of their work elsewhere.

Then what kind of closure will we have?

-Wes

From Day 1, these are the pieces of medicine that are hammered in to young doctors' heads: the best way to treat this or that, the best drug, widget or gizmo, the latest advance. We learn which approach is better than the other, which treatment to apply when more conventional approaches can't be taken. Each of these steps are drilled over and over again in the hopes of crafting a strategy for each clinical scenario a doctor is likely to encounter. Yet while each of these steps that are learned are important in their own right, few of these steps are critical to doctors' sustainability in their profession.

Because after the treatment strategy or therapy is applied, there's another vital part of the medical care that is often under-appreciated for doctors and policy makers: the closure.

"Closure" is the time in medicine where we either revel in our success or squirm in our failure. It's where we must face the music - good or bad - with our patients. More often than not, it's the time for doctors that brings meaning to our efforts and the hours we work.

Closure can occur at different times for different doctors. For specialists (increasingly called "proceduralists" these days), closure usually occurs in the post-operative or post-procedure period. For primary care doctors, "closure" occurs during the follow-up visit after a prolonged hosptitalization or difficult illness. For both types of doctors, it's the chance to see the good they did or bad they did first-hand. It a time to validate their understanding of the patient's ailment and the caliber of their treatment plan. Importantly, it's not the end of the patient's ongoing care but rather, it's the conclusion to a particular chapter of their care. For doctors, it's the critical time we grow as professionals.

Yet sadly, these moments of closure are becoming rarer for both the patient and the doctor.

With doctors racing between facilities on productivity compensation plans who must perform more cases in less time and in more locations to offset declining payment rates, it's become harder both logistically and financially to justify excessive post-operative time with patients after their procedures. The money required to feed the our massive system of administrators, collectors, quality score counters, overheads and salaries demands a constant ever-growing source of funds, so doctors must keep moving.

To that end, specialist physicians have seen post-operative care routinely clumped together with the pre-procedure and intra-operative care as one big "encounter" that pays health systems only once. Increasingly to add "value" to health care dollars, policy makers are shifting the "risk" of caring for patients to the providers of that care. Insurers and policy makers like to call this shifting from "procedural-based" payments to "outcome-based" payments. In theory this sounds nice, but it's robbing the doctors of the closure time so critical in the valuation of their profession in favor of treating a greater quantity of healthier, lower-risk patients to assure reliable payments to the system.

For primary care doctors who now only see patients in their offices, the opporunity to see the product of a continuous care strategy has been surrendered to the hospitalist movement robbing them of closure time. And even the hospitalists who "diagnose and say 'adios'" from the confines of the hospital, the opportunity see the late consequences of their care in a non-critical environment has been lost to production quotas as well. No fractious group "medical home" care in the world can replace this loss of closure inflicted upon primary care and shift-working hospitalist physicians or the patients for whom they care.

Our health policy analysts have assured us these "closure" visits can be accomplished by ancillary care providers. Technically, they are correct. But there is no question that the loss of these post-procedure visits by the treating physician or operating surgeon robs them of a critically important opportunity for continuous self-improvement as they reflect on the quality and cailber of their work first-hand. Further, doctors lose an opportuntity after the haze of amnestic medications have subsided to educate and re-connect. Doctors need this time with their patients just like patients like this time with their doctors - maybe even more. It's what makes it worthwhile to get up and do it all again.

Despite the current push, I still try to see my patients after a procedure whenever possible. Sure, we don't get paid for this, but I still relish a patient's gentle smile or a quiet "thank you." More importantly, when things aren't perfect, I need the opportunity to reassure and console. If things really don't go well, I find there are huge benefits derived when I can explain and empathize with the patient's situation.

Still, I feel the tug. "It's not efficient," they tell me.

Perhaps.

But it's this closure that sustains me and I suspect sustains many in our profession. And honestly? If doctors' closure time continues to be parsed and devalued further, they'll look for validation of their work elsewhere.

Then what kind of closure will we have?

-Wes

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Who Should Be Prescribed Dronedarone?

With Sanolfi's release today of their dear doctor letter restricting the use of dronedarone to patients without permanent atrial fibrillation OR atrial flutter, we are left to wonder why paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patient therapy is any safer. (We are also left to ask why the letter is hidden behind MedScape's registration process rather than easily accessible on their website, but that's another matter to take up another day).

Why the quandry? Because of how permanent atrial fibrillation was defined for the study:

"Persistent" atrial fibrillation are those patients in atrial fibrillation who CAN be converted to sinus rhythm using cardioversion and whose event lasts more than seven days.

Which leads to the logical question: how many "persistant" afib patients were part of the PALLAS patient population and might "persistant" atrial fibrillation patients be similarly at risk?

It's all as clear as mud.

-Wes

Why the quandry? Because of how permanent atrial fibrillation was defined for the study:

Permanent AF was defined by the presence ofDoes merely electing to not attempt a cardioversion on a patient with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter truly define "permanent" atrial fibrillation? Not typically - usually we define permanent atrial fibrillation as someone who fails elective cardioversion long-term. But for the intent and purpose of the PALLAS trial on which the "Dear Doctor" letter is based, it is how the "permanence" of atrial fibrillation was defined.

AF/atrial flutter (AFL) for at least 6 months prior to randomization and patient/physician decision to allow AF to continue without further efforts to restore sinus rhythm.

"Persistent" atrial fibrillation are those patients in atrial fibrillation who CAN be converted to sinus rhythm using cardioversion and whose event lasts more than seven days.

Which leads to the logical question: how many "persistant" afib patients were part of the PALLAS patient population and might "persistant" atrial fibrillation patients be similarly at risk?

It's all as clear as mud.

-Wes

The Clinical Costs of Pharmachologic Post-Market Surveillance

Every drug a doctor prescribes requires an intimate knowledge of the drug's pharmacology, side effects, and possible drug interactions. Nowhere is this more true than antiarrhythic drugs. Concern over side effects with government regulators has reached a fever pitch since there is realization that all the pre-market randomized controlled trials often fail to identify later problems with medications. A classic example of this is dronedarone, initially heralded as a "safer" amiodarone substitute, but was later implicated in rare instances of fulminant hepatic failure.

While post-market surveillance of medications is both necessary and warranted, it is interesting to me how the grunt work of this surveillance (and most other grand regulatory schemes) falls squarely on the backs of physicians rather than the drug companies who manufacture and profit from the medications.

Case in point: the FDA's REMS program. REMS stands for "Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy" and is a program developed by the FDA "to manage known or potential serious risks associated with a drug product. It is required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ensure that the benefits of a drug outweigh its risks." It covers an increasingly large array of medications.

But what does this grand plan require the drug companies to do?

Drug companies must create a database.

But for doctors who prescribe these antiarrhythmic medications and are board-certified to do so, we now have to perform a "one-time" re-certification that involves filling out a form and agreeing, in writing, to mandated patient appointment frequencies and minimum requirements for patient education that must be conducted during our office visits.

Such is the case with Pfizer's antiarrhythmic medication dofetilide (marketed as Tikosyn). Realize this "re-certification" comes AFTER we have all had to conduct a training regimen and were already registered with the company to prescribe the drug.

The REMS program, begun in 2008, grew more inclusive (and intrusive) after identification of a White House "crisis" involving prescription drug abuse of opioid analgesics that surfaced in April of this year. This edict has now trickled down to the clinical front lines of care with some very significant clinical consequences.

As clinical volumes rise, doctors are finding it increasingly difficult to reach the Utopian vision of frequent patient follow-up for drug surveillance for the pharmaceutical industry. Certainly, if there is clinical reason to do so (marginal renal function, higher-dose therapy, confounding medical issues) we see patients more frequently as needed. But in stable, relatively healthy patients who have a history of safely using these medications, we are left to wonder if the FDA's surveillance program has the potential to limit our ability to see new patients in favor of only managing established patients on chronic medication regimens that require close follow-up.

Clearly, there should be a balance. For many doctors (myself included) we have had to resort to using a nurse practitioner to assist with this requirement to offload the crush of such mandated patient visits. But for doctors in smaller, more rural settings where ancillary care providers are harder to come by, I suspect others will quickly saturate their clinics with regulated patient visits or else just not offer these medications to their patients.

This balance of safety and quality care to the oncoming tsunami of patients sure to hit our door in 2014 is an interesting dilemma not easily solved. Still, innovative ways to avoid top-down regulations that are crushing doctors with mandated (and often clinically unnecessary) care will go a long way to improving the quantity of care we are able to provide our growing population of patients.

-Wes

While post-market surveillance of medications is both necessary and warranted, it is interesting to me how the grunt work of this surveillance (and most other grand regulatory schemes) falls squarely on the backs of physicians rather than the drug companies who manufacture and profit from the medications.

Case in point: the FDA's REMS program. REMS stands for "Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy" and is a program developed by the FDA "to manage known or potential serious risks associated with a drug product. It is required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ensure that the benefits of a drug outweigh its risks." It covers an increasingly large array of medications.

But what does this grand plan require the drug companies to do?

Drug companies must create a database.

But for doctors who prescribe these antiarrhythmic medications and are board-certified to do so, we now have to perform a "one-time" re-certification that involves filling out a form and agreeing, in writing, to mandated patient appointment frequencies and minimum requirements for patient education that must be conducted during our office visits.

Such is the case with Pfizer's antiarrhythmic medication dofetilide (marketed as Tikosyn). Realize this "re-certification" comes AFTER we have all had to conduct a training regimen and were already registered with the company to prescribe the drug.

The REMS program, begun in 2008, grew more inclusive (and intrusive) after identification of a White House "crisis" involving prescription drug abuse of opioid analgesics that surfaced in April of this year. This edict has now trickled down to the clinical front lines of care with some very significant clinical consequences.

As clinical volumes rise, doctors are finding it increasingly difficult to reach the Utopian vision of frequent patient follow-up for drug surveillance for the pharmaceutical industry. Certainly, if there is clinical reason to do so (marginal renal function, higher-dose therapy, confounding medical issues) we see patients more frequently as needed. But in stable, relatively healthy patients who have a history of safely using these medications, we are left to wonder if the FDA's surveillance program has the potential to limit our ability to see new patients in favor of only managing established patients on chronic medication regimens that require close follow-up.

Clearly, there should be a balance. For many doctors (myself included) we have had to resort to using a nurse practitioner to assist with this requirement to offload the crush of such mandated patient visits. But for doctors in smaller, more rural settings where ancillary care providers are harder to come by, I suspect others will quickly saturate their clinics with regulated patient visits or else just not offer these medications to their patients.

This balance of safety and quality care to the oncoming tsunami of patients sure to hit our door in 2014 is an interesting dilemma not easily solved. Still, innovative ways to avoid top-down regulations that are crushing doctors with mandated (and often clinically unnecessary) care will go a long way to improving the quantity of care we are able to provide our growing population of patients.

-Wes

Friday, August 12, 2011

The Challenges of Medical Device Follow-up

With the explosion of medical devices to treat various medical ailments in medicine, we have seen significant improvements in quality and quantity of life. An underappreciated consequence of all of these electronic device therapies, however, has been the manpower and expertise required to manage these implanted electronic medical devices long-term.

Problems with electromagnetic interference (EMI) with medical devices are real. Innovations in medicine have come from various portions of the electromagnetic spectrum including analog and digital wireless technology, diagnostic and therapeutic radiation therapy and magnetic resonance imaging. The effects of these technologies on implanted electronic medical devices can vary and specialty physicians, ancillary health care providers, and medical device manufacturers expend significant man-hours managing these potential interference sources and their affects on devices without a single prospective randomized trial to guide us. The sheer number of devices and the many ways that EMI can interfere with these complex devices makes constructing an all-inclusive trial with sufficient number of "events" to compare difficult or nearly impossible. As a result, most of our management recommendations and hospital policies in this regard have been based from literature case reports or personal experience and expertise.

To date, recommendations for minimizing EMI with cardiac implantable electronic devices has been sorely lacking, so the new recommendations published (1.3 Meg pdf) recently by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) in conjunction with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) should serve as a helpful guide for physicians involved in the management of these devices. It would be well beyond the scope of this blog to include all of the pre-procedural, intra-procedural and post-procedural recommendations made by this document. But there are some other limitations to these recommendations that warrant mention.

First, there are a multitude of makes and models of pacemaker and implantable cardiac defibrillator devices which are covered by this document. The document is fairly inclusive regarding today's technology. New models forthcoming, however, are not specifically covered by this document (how can they be?) so the challenges keeping these recommendations current will remain a challenge.

Secondly, these recommendations do not cover the management of devices during magnetic resonance imaging, an evolving innovation in these devices, but no less important for patient management in these procedures.

Third, this document covers only implantable electronic cardiac devices. Nerve stimulators, brain stimulators, insulin pumps and a whole host of other implanted electronic devices still remain outside the purview of these recommendations, yet pose similar challenges to patient management, both from a technical expertise AND manpower-need standpoint. The challenges of not only electromagnetic interference, but also device-device interference remain and still need to be considered clinically.

Finally, the recommendations were made in conjunction with the expertise of industry and physician experts. While these recommendations appear to have been made for patients benefit, the real need for the medical device industry to limit their manpower needs for peri-procedural device checks should not go unnoticed. Much of the newer innovations of home monitoring has been forwarded in part to address these simultaneous patient and industry needs. Still, it goes without saying that doctors should remember that any local hospital recommendations developed on the basis of these guidelines should always put the needs of the patient before those of the medical device industry or hospital administration.

-Wes

Reference: The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Expert Consensus Statement on the Perioperative Management of Patients with Implantable Defibrillators, Pacemakers and Arrhythmia Monitors: Facilities and Patient Management.

Problems with electromagnetic interference (EMI) with medical devices are real. Innovations in medicine have come from various portions of the electromagnetic spectrum including analog and digital wireless technology, diagnostic and therapeutic radiation therapy and magnetic resonance imaging. The effects of these technologies on implanted electronic medical devices can vary and specialty physicians, ancillary health care providers, and medical device manufacturers expend significant man-hours managing these potential interference sources and their affects on devices without a single prospective randomized trial to guide us. The sheer number of devices and the many ways that EMI can interfere with these complex devices makes constructing an all-inclusive trial with sufficient number of "events" to compare difficult or nearly impossible. As a result, most of our management recommendations and hospital policies in this regard have been based from literature case reports or personal experience and expertise.

To date, recommendations for minimizing EMI with cardiac implantable electronic devices has been sorely lacking, so the new recommendations published (1.3 Meg pdf) recently by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) in conjunction with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) should serve as a helpful guide for physicians involved in the management of these devices. It would be well beyond the scope of this blog to include all of the pre-procedural, intra-procedural and post-procedural recommendations made by this document. But there are some other limitations to these recommendations that warrant mention.

First, there are a multitude of makes and models of pacemaker and implantable cardiac defibrillator devices which are covered by this document. The document is fairly inclusive regarding today's technology. New models forthcoming, however, are not specifically covered by this document (how can they be?) so the challenges keeping these recommendations current will remain a challenge.

Secondly, these recommendations do not cover the management of devices during magnetic resonance imaging, an evolving innovation in these devices, but no less important for patient management in these procedures.

Third, this document covers only implantable electronic cardiac devices. Nerve stimulators, brain stimulators, insulin pumps and a whole host of other implanted electronic devices still remain outside the purview of these recommendations, yet pose similar challenges to patient management, both from a technical expertise AND manpower-need standpoint. The challenges of not only electromagnetic interference, but also device-device interference remain and still need to be considered clinically.

Finally, the recommendations were made in conjunction with the expertise of industry and physician experts. While these recommendations appear to have been made for patients benefit, the real need for the medical device industry to limit their manpower needs for peri-procedural device checks should not go unnoticed. Much of the newer innovations of home monitoring has been forwarded in part to address these simultaneous patient and industry needs. Still, it goes without saying that doctors should remember that any local hospital recommendations developed on the basis of these guidelines should always put the needs of the patient before those of the medical device industry or hospital administration.

-Wes

Reference: The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Expert Consensus Statement on the Perioperative Management of Patients with Implantable Defibrillators, Pacemakers and Arrhythmia Monitors: Facilities and Patient Management.

Tuesday, August 09, 2011

The Cost of Our Medical Licensure Complex

You could see the frustration in his eyes as he spoke to his fellow resident.

"I had to fork over eight hundred and thirty five dollars," he said slowly in a disgusted tone, "... and that doesn't even include the $300 state license fee we have to pay later...."

So much for starting our EKG conference on time.

The comments continued. No one could understand why medical school licensure has become so expensive in the US. I thought I'd look into what medical students can expect to pay these days for licensure since it had been a while since I had gone through the gauntlet. Here's what I found out:

A good overview can be found on the Wikipedia website. I'll direct readers there who want specifics as a starter. What I was more interested in were the sheer numbers of organizations and people involved in this process of verification of credentials and managing a series of tests that have become known as the US Medical Licensure Examination (USMLE).

First, there is the National Board of Medical Examiners. Then there's the Federation of State Medical Boards. Then there's the Education Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates. And let's not forget the Foundation for the Advancement of International Medical Education and Research, whom the US medical students support, in part, so tests can be administered to foreign medical students in an effort to advance international medical education and research. It's a veritable cornucopia of testing services for the whole world!

So no wonder the resident was frustrated. He's been paying into an industry that's getting quite expensive: over three thousand dollars expensive.

How can that be?

Well, the toll is paid gradually by medical students and residents - it's easier to pay in "steps," it seems. Here's the breakdown for 2011:

USMLE Step 1: $525

USMLE Step 2, Clinical Knowledge (CK): $525

USMLE Step 2, Clinical Skills (CS): $1120 (Oh, if you're not from Philadelphia, PA, Chicago, IL, Atlanta, GA, Houston, TX or Los Angeles, CA, then please add hotel and transportation fees, since this part is offered only in those cities.)

... and then you have to check with you local state licensure board for the fees associated with USMLE Step 3. For Illinois (pdf) (from where the disgruntled voices rose):

Fee for Continental Testing Services, Inc.: $105

Fee to the Federation State Medical Board: $730

Total USMLE Step 3 Fee in IL: $835

And that doesn't include the later $300 IL state medical licensure fee to be paid later. (Other states are likely to be different)

Which leads to the Grand Total for licensure for an Illinois-based US medical student today:

$3,305.

This on top of how much medical school debt?

No wonder the resident was upset.

(Good thing I didn't mention his upcoming board certification fees.)

-Wes

In the mail: "Dr. Wes, internists aren't 'fleas' any more, they're the dogs from which the fleas suck."

"I had to fork over eight hundred and thirty five dollars," he said slowly in a disgusted tone, "... and that doesn't even include the $300 state license fee we have to pay later...."

So much for starting our EKG conference on time.

The comments continued. No one could understand why medical school licensure has become so expensive in the US. I thought I'd look into what medical students can expect to pay these days for licensure since it had been a while since I had gone through the gauntlet. Here's what I found out:

A good overview can be found on the Wikipedia website. I'll direct readers there who want specifics as a starter. What I was more interested in were the sheer numbers of organizations and people involved in this process of verification of credentials and managing a series of tests that have become known as the US Medical Licensure Examination (USMLE).

First, there is the National Board of Medical Examiners. Then there's the Federation of State Medical Boards. Then there's the Education Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates. And let's not forget the Foundation for the Advancement of International Medical Education and Research, whom the US medical students support, in part, so tests can be administered to foreign medical students in an effort to advance international medical education and research. It's a veritable cornucopia of testing services for the whole world!

So no wonder the resident was frustrated. He's been paying into an industry that's getting quite expensive: over three thousand dollars expensive.

How can that be?

Well, the toll is paid gradually by medical students and residents - it's easier to pay in "steps," it seems. Here's the breakdown for 2011:

USMLE Step 1: $525

USMLE Step 2, Clinical Knowledge (CK): $525

USMLE Step 2, Clinical Skills (CS): $1120 (Oh, if you're not from Philadelphia, PA, Chicago, IL, Atlanta, GA, Houston, TX or Los Angeles, CA, then please add hotel and transportation fees, since this part is offered only in those cities.)

... and then you have to check with you local state licensure board for the fees associated with USMLE Step 3. For Illinois (pdf) (from where the disgruntled voices rose):

Fee for Continental Testing Services, Inc.: $105

Fee to the Federation State Medical Board: $730

Total USMLE Step 3 Fee in IL: $835

And that doesn't include the later $300 IL state medical licensure fee to be paid later. (Other states are likely to be different)

Which leads to the Grand Total for licensure for an Illinois-based US medical student today:

$3,305.

This on top of how much medical school debt?

No wonder the resident was upset.

(Good thing I didn't mention his upcoming board certification fees.)

-Wes

In the mail: "Dr. Wes, internists aren't 'fleas' any more, they're the dogs from which the fleas suck."

Friday, August 05, 2011

Break Time

I'll be dropping off the electronic grid for a while for a weekend in northern Wisconsin. Have a great weekend.

-Wes

How My iPhone Prevented an ER Visit (with screenshots)

It's one of those calls you never want to get as an electrophysiologist:

Booting the app:

The login screen:

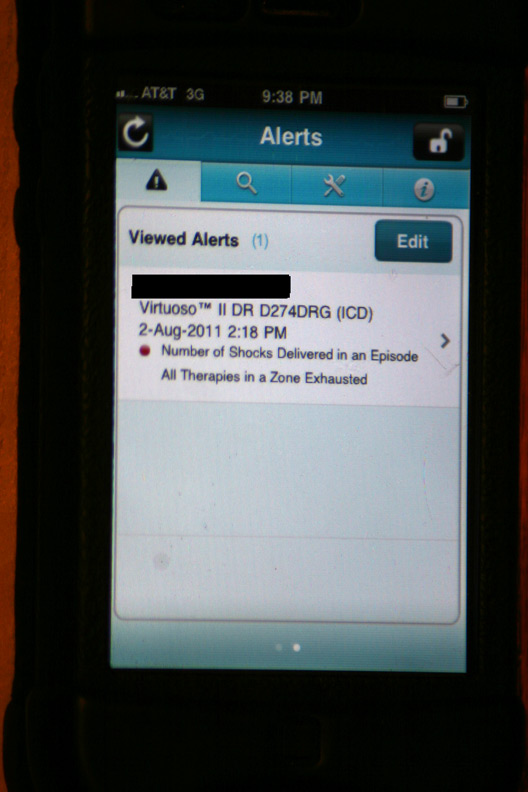

The initial alert that appeared after logging in:

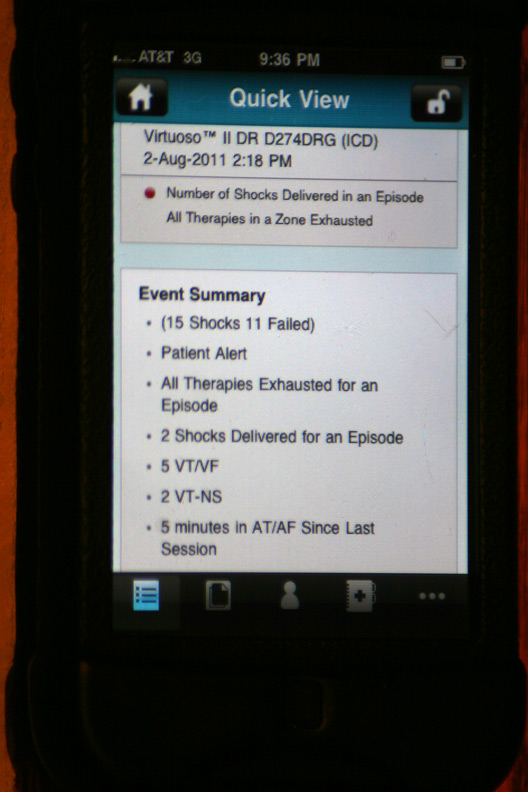

The gory details of that event displayed after touching the above alert (Holy cow! He had a lot more than four shocks!):

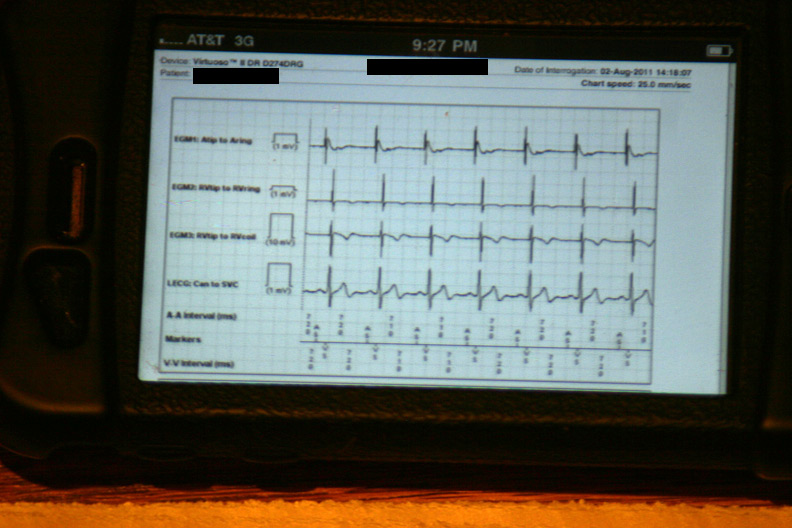

The data were then loaded from the event in a 42-page unprintable pdf file (HIPAA prevents printing, I guess). Page one contained the various atrial and ventricular electrograms (signals from the wires in his heart) at the time the data were transmitted:

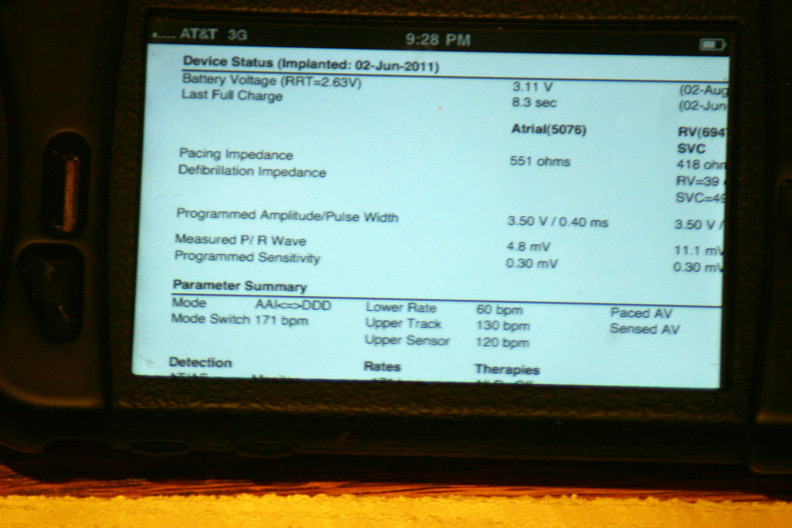

A few of the basic programmed parameters and remaining battery life (Whew, plenty left!):

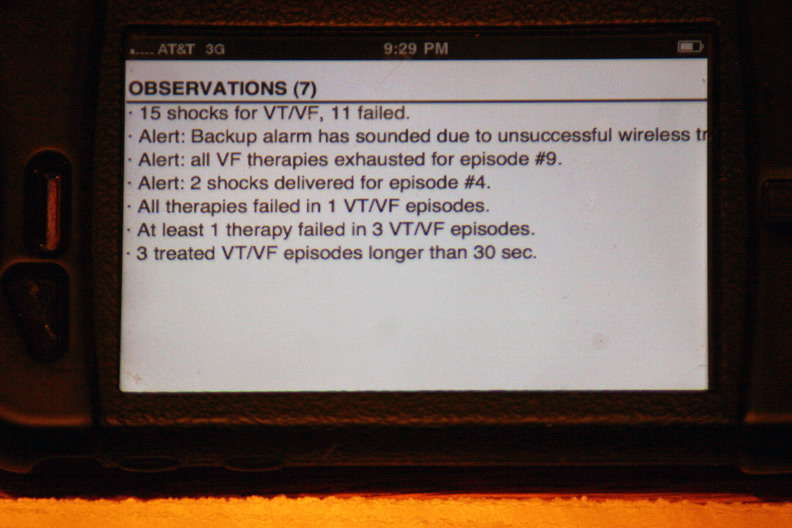

The device's seven "observations" classifying the types and numbers of therapies:

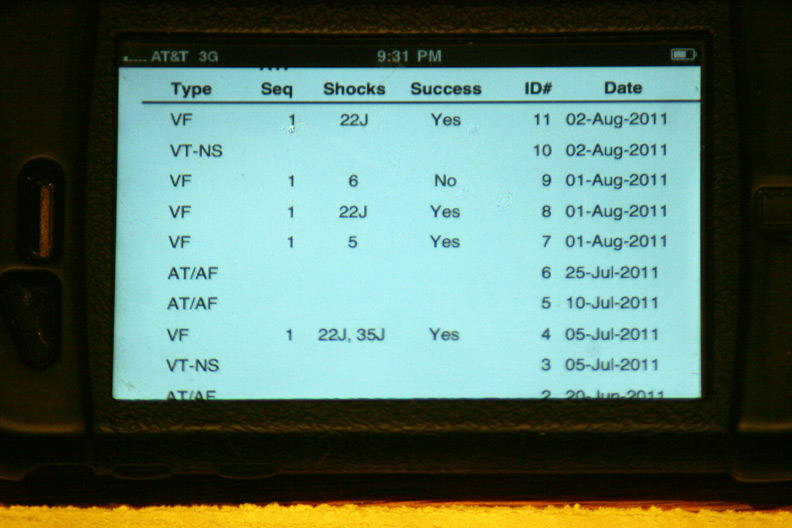

More specifics regarding the time and number of shocks at each event:

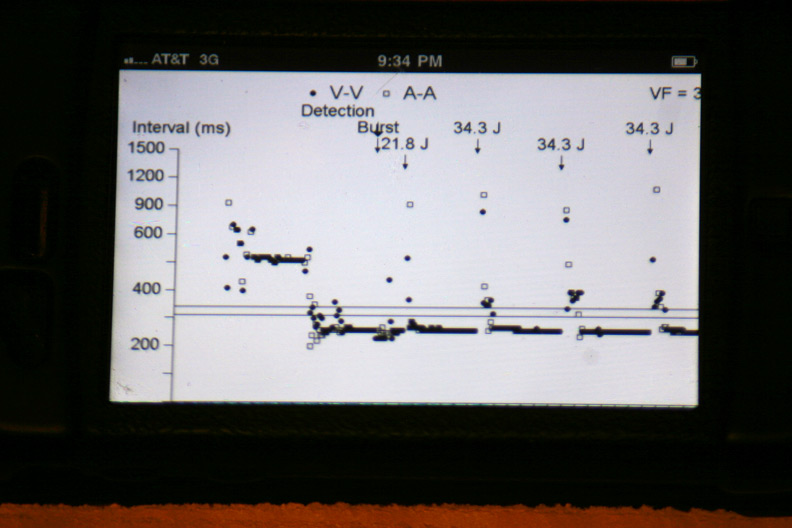

The atrial and ventricular inter-electrogram interval plot for the most recent event with repetitive shocking:

Zooming in on the plot of atrial (squares) and ventricular (circles) intervals at the intitiation of the event (Who started things?):

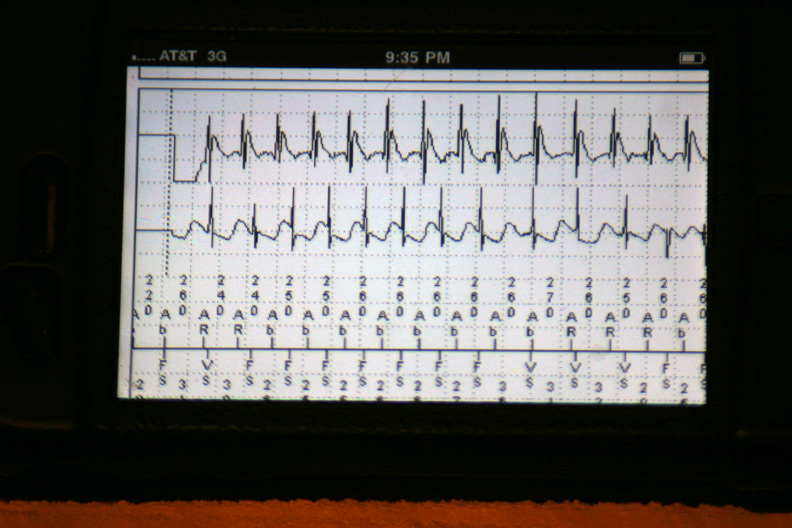

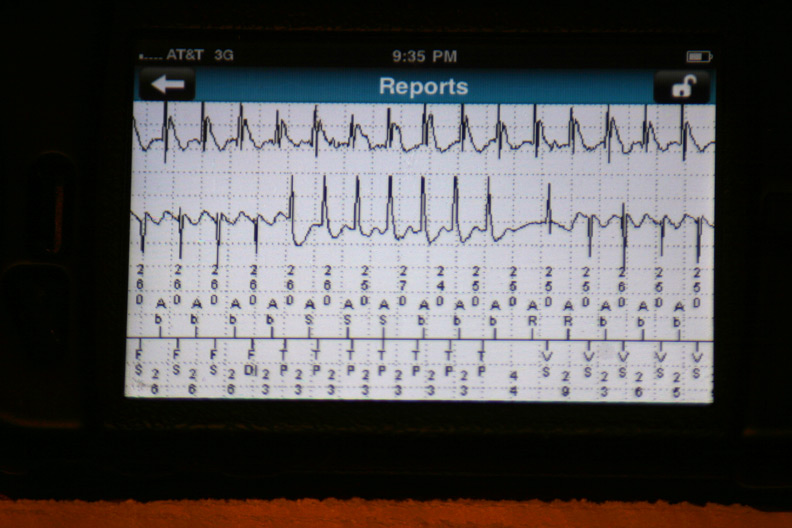

The atrial and ventricular electrograms obtained during one of the events (Is that Wenckebach block?):

The effect of antitachycardia pacing during the event: the ventricle is paced but had no effect on the atrium driving the ongoing event:

The other events disclosed similar findings. It appeared each of these shock therapies were delivered as a result of a very fast atrial tachycardia that was able to conduct to the ventricle, rather than a ventricular rhythm problem.

Of course, there is a slight problem that presents itself to doctors and their business administrators when we use this very cool technology: it's all done for free. Still, the ability to review this important clinical information untied to a hard-wired computer terminal offers important advantages to our increasingly mobile physician workforce and, in this case, prevented an unnecessary emergency room visit.

-Wes

Epilogue: The patient was contacted by phone after reviewing this information. He as told he did not have to go to the Emergency Room. Instead, significant adjustments were made to his medication regimen over the phone. He was seen the next morning in our device clinic to reset the alarm that was triggered when his device exhausted all its therapies in one event. No further arrhythmias had transpired and discussions regarding alternate medical or ablative therapies are pending.

P.S.: Sorry patients, the while the app can be downloaded from the Apple iTunes App store for free, its use is restricted to authorized care providers only. Maybe when implantable devices carry memory bins for uploaded digital music...

"Doc, I got four shocks from my device yesterday."So I waited about 15-20 minutes, then checked the Medtronic Carelink app on my iPhone. This application lets doctors and device management personnel view all of the information uploaded from pacemakers and defibrillators that we normally review in our device clinics on our iPhones instead. I hadn't had much need for this, or so I thought, until now. I thought it would be cool for patients to see what their authorized doctors can view on their iPhones when things like this occur, so I took some screenshots.

"What were you doing at the time?"

"Working outside."

"Wasn't it about a 100 degrees and humid then?"

"Yes."

"Were you lightheaded before the event?"

"Not too bad... I stopped what I was doing and got better. Should I come in to the ER?"

"This happened yesterday?"

"Yes."

"Why didn't you come in then?"

"Well I started to feel better..."

"Do you know how to upload the information from your device at home?"

"You mean using that thing next to my bed?"

"Yes."

"I think so."

"Okay, why don't you go do this and we'll call you right back after we have a chance to view the information you send us."

"Okay. Thanks, doctor."

Booting the app:

Click on any image to enlarge

The login screen:

The initial alert that appeared after logging in:

The gory details of that event displayed after touching the above alert (Holy cow! He had a lot more than four shocks!):

The data were then loaded from the event in a 42-page unprintable pdf file (HIPAA prevents printing, I guess). Page one contained the various atrial and ventricular electrograms (signals from the wires in his heart) at the time the data were transmitted:

A few of the basic programmed parameters and remaining battery life (Whew, plenty left!):

The device's seven "observations" classifying the types and numbers of therapies:

More specifics regarding the time and number of shocks at each event:

The atrial and ventricular inter-electrogram interval plot for the most recent event with repetitive shocking:

Zooming in on the plot of atrial (squares) and ventricular (circles) intervals at the intitiation of the event (Who started things?):

The atrial and ventricular electrograms obtained during one of the events (Is that Wenckebach block?):

The effect of antitachycardia pacing during the event: the ventricle is paced but had no effect on the atrium driving the ongoing event:

The other events disclosed similar findings. It appeared each of these shock therapies were delivered as a result of a very fast atrial tachycardia that was able to conduct to the ventricle, rather than a ventricular rhythm problem.

Of course, there is a slight problem that presents itself to doctors and their business administrators when we use this very cool technology: it's all done for free. Still, the ability to review this important clinical information untied to a hard-wired computer terminal offers important advantages to our increasingly mobile physician workforce and, in this case, prevented an unnecessary emergency room visit.

-Wes

Epilogue: The patient was contacted by phone after reviewing this information. He as told he did not have to go to the Emergency Room. Instead, significant adjustments were made to his medication regimen over the phone. He was seen the next morning in our device clinic to reset the alarm that was triggered when his device exhausted all its therapies in one event. No further arrhythmias had transpired and discussions regarding alternate medical or ablative therapies are pending.

P.S.: Sorry patients, the while the app can be downloaded from the Apple iTunes App store for free, its use is restricted to authorized care providers only. Maybe when implantable devices carry memory bins for uploaded digital music...

Thursday, August 04, 2011

When Drugs Go Off the Radar

With the news that Pfizer is considering the possibility of making Lipitor (atorvastatin) over-the-counter (OTC), the FDA suddenly becomes "concerned:"

Mixed messages, anyone?

People only have so much money these days, so willful consumption of a relatively expensive OTC drug like Lipitor will likely only occur if (1) people feel they really need it and (2) if it proves to be affordable relative to the co-pay they have to pay from an insurer's plan. Pfizer realizes that most doctors consider their medication to be relatively safe. I suspect most cardiologists would agree with that sentiment.