She sat at the dining room table, counting.

"Let's see, a pink one, the tiny one, a big blue one, another one of those other white ones, the yellow one... oh, I don't take THAT white one until noon ... then one of those and one of those. There. I think I've got it."

She scraped then all in a little pile on the table, then swept them in her hand and tossed to pill pile into her mouth as she chased them all down with a slosh of water, looking a bit like a pelican downing an oversized fish.

"Ahhhh," she said. "Now, how about breakfast?"

I sat in amazement as I looked at my mother-in-law's pill pile. It really wasn't anything over the top: the usual medications for coronary disease, hypertension, adult-onset diabetes - all things I've prescribed a thousand times. But I could not help but wonder how our patients keep all this stuff straight.

Most doctors don't think twice about adding another drug here and there. After all, we always seem to have such a good grasp of pharmacology that we're absolutely convinced, I mean CONVINCED, that our new drug is important for our patient's management. But recently in the hospital I've noticed a problem that seems to be becoming more common: drug-drug interactions, or more accurately: drug-drug-drug-drug-drug interactions that can lead to unintended or unsuspected side effects, especially (in my case) cardiac arrhythmias.

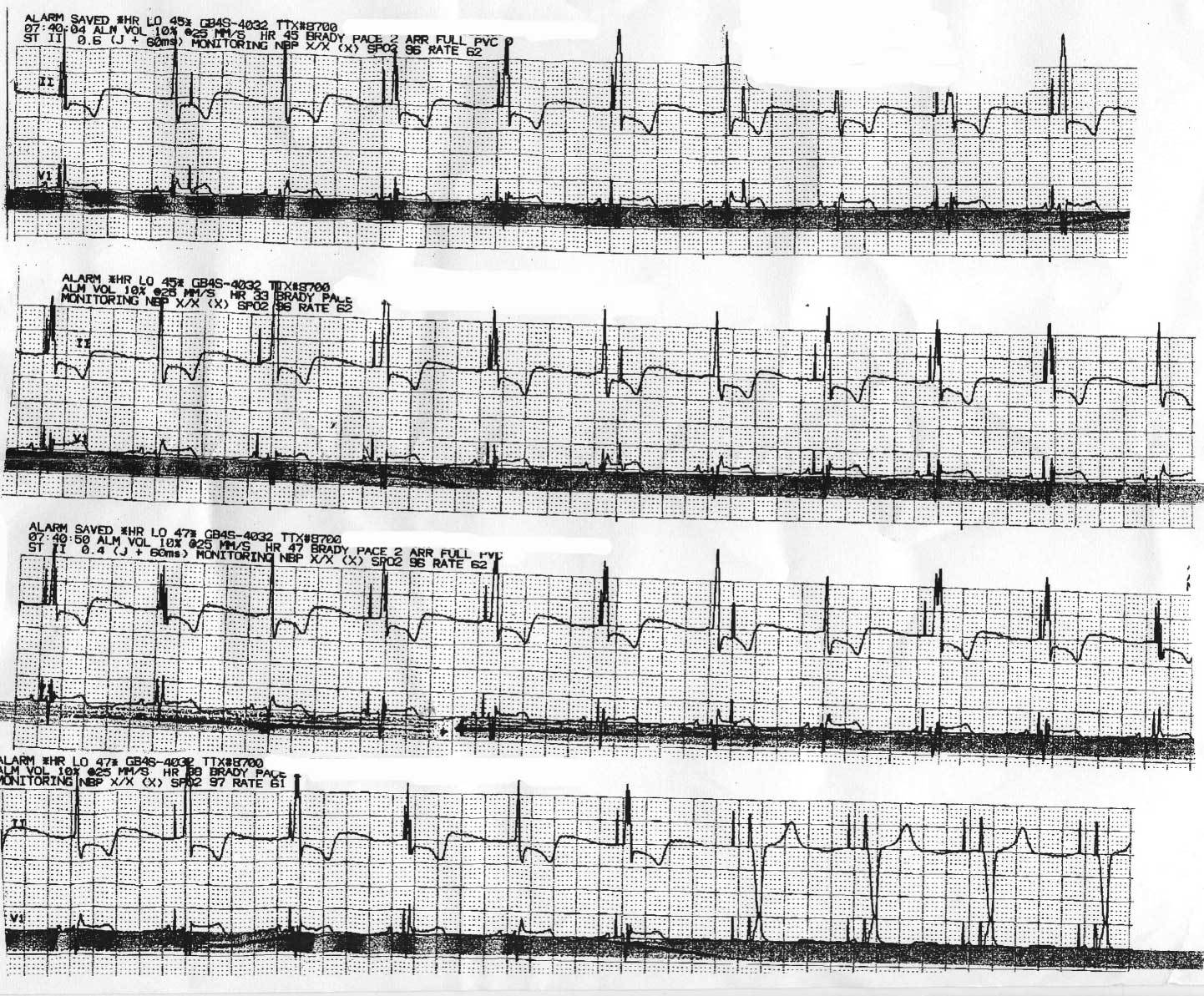

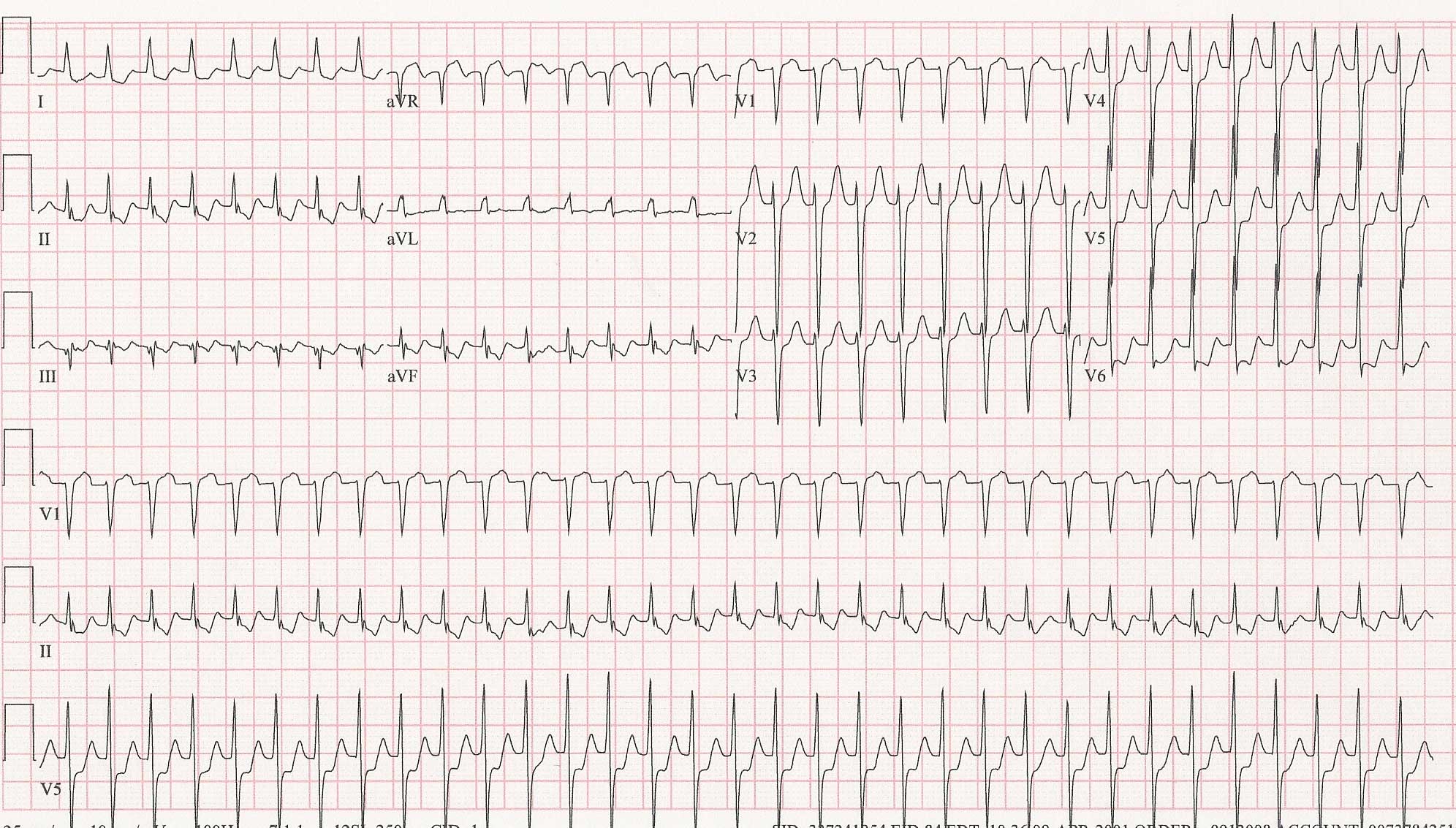

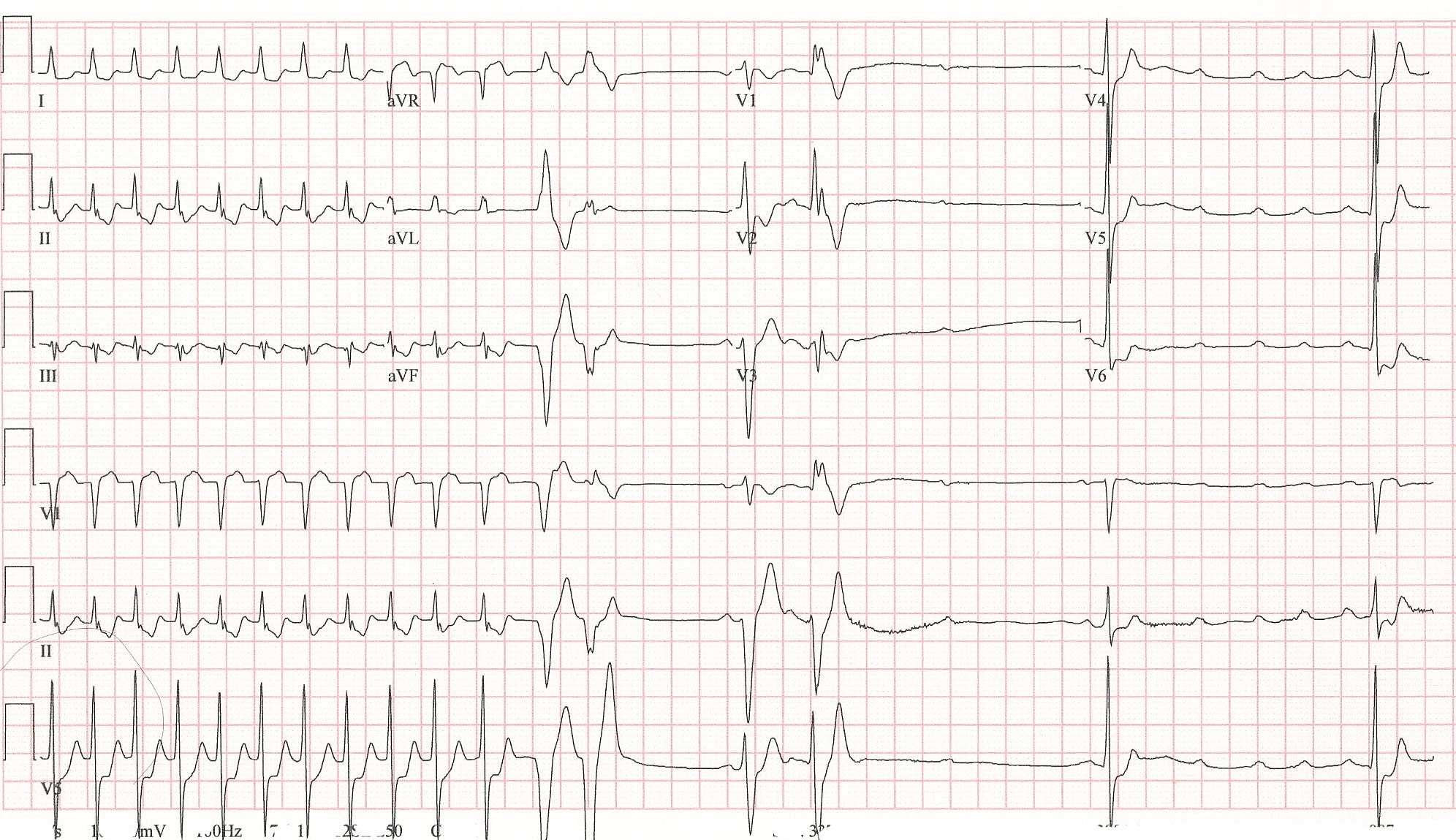

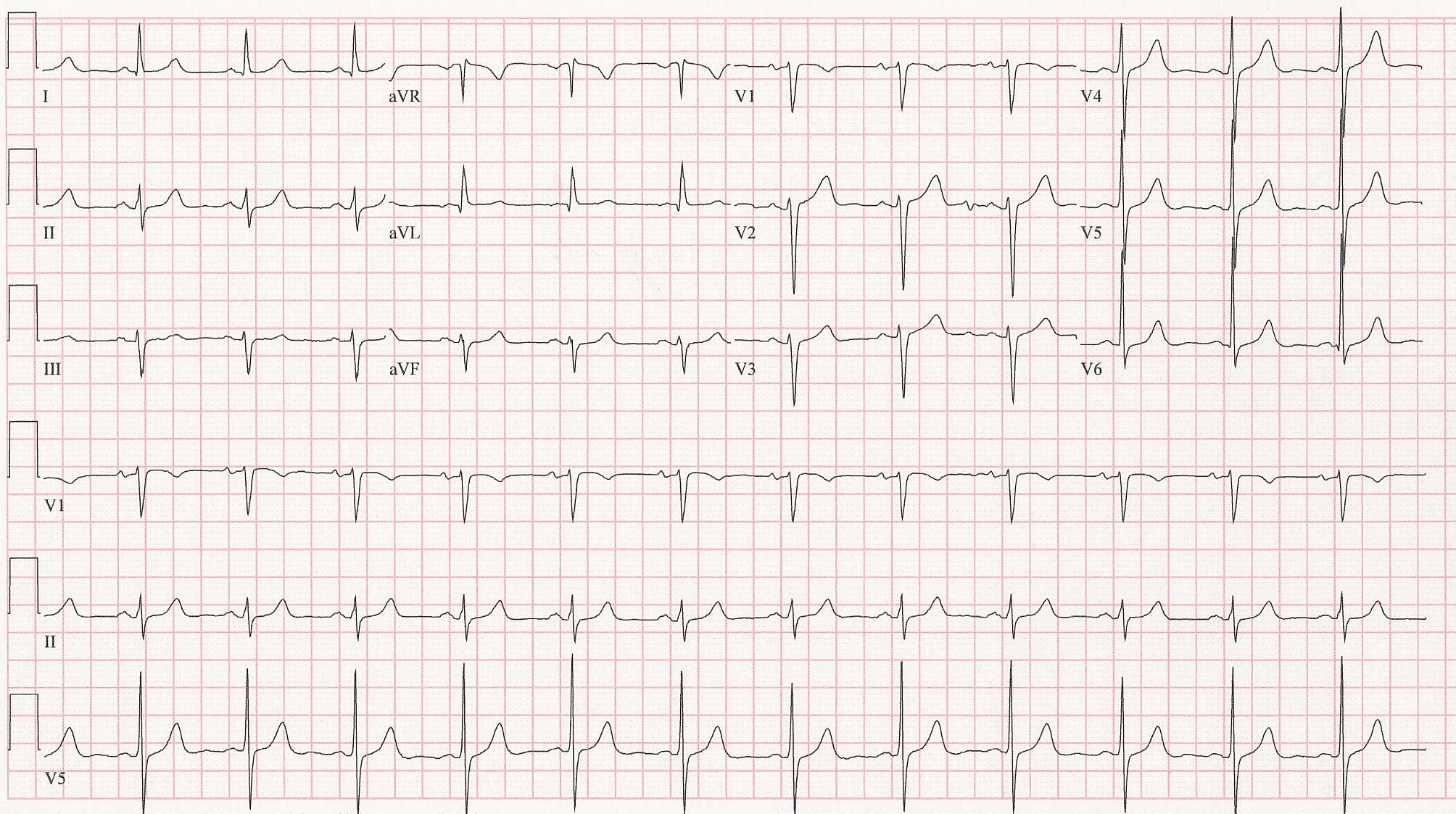

These interactions are becoming tougher to identify as polypharmacy increases in America. Which drug causes what effect can be particularly challenging when people take plenty of different medicines. Nowhere is this more common than with psychotropic medications, especially tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepresants which might be coupled with analgesics, antibiotics, antifungal agents or sleeping medications and the like. Often, these make the perfect cocktail for cardiac catastrophe. We see this on the ward (if we're lucky) as polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or "torsades de pointes" (so-called "twisting around the points") - a malignant heart rhythm disorder caused by excessive prolongation of a resetting current for cardiac contraction called "repolarization." With the right circumstances and when it occurs at the correct time, a single skipped heart beat can cause the heart rhythm to lose all coordination and just quiver, effectively stopping the flow of blood to the brain. Also, sedatives can exacerbate sleep apnea and its resultant hypoxia (low oxygen level). Hypoxia, if significant enough, can cause significant cardiac slowing or even complete heart block.

I wonder, in all the sadness and turmoil surrounding Michael Jackson's recent death, if this same problem might have led to this popular pop icons' demise as well. By now, we have "heard" that Mr. Jackson was

given an injection of Demerol (

propoxyphene meperidene) shortly before his death. If so, demerol is usually given intramuscularly. But it would not be too inconceivable that one shot might have accidentally been injected into the vascular system, causing rapid sedation and overwhelming his drive to breathe. Follow this respiratory suppression with a few other psychotropic, analgesic medications, antibiotics or sleep aides, and not only might additional sedation occur, but a lethal cardiac arrhythmia as well, even in someone with totally normal coronary arteries.

To me, this scenario seems a much more plausible cause for Mr. Jackson's death rather than a massive heart attack, but then, since I do not have the benefit of reviewing his autopsy results, my thoughts are really nothing more than an educated guess.

No doubt by now there are a multitude of other guesses out there, a million opinions, and even more possibilities regarding the cause of Mr. Jackson's death. Everyone wants and, probably,

needs an answer. Unexpected death is like that. But whether a definitive answer is ever found or whether the world will be permitted to learn the true answer is unknown at this point. Family takes precedence, in my view. But maybe there's some other take-home messages we can gain from this sad circumstance.

For one, we have become a pill culture, reaching for pills to cure almost anything and everything. We gobble them down often with barely a thought about their side effects as we eagerly seek a simple fix for what is often very difficult problems. Certainly, there there are scores of miraculous agents out there that have improved the quality and quantity of life for millions of us. (I am

not advocating anyone stop any meds as a result of this blog post!) But I have become jaded about psychotropic and sedative medications because of my vocation as a heart rhythm specialist, especially when they are used in combination with other medications that can potentiate their effects or alter cardiac activity. Although drug companies have excellent testing to assure new drugs' safety, they simply cannot test the multiple permutations and combinations of medications on the market with their drug. New interactions are found all the time. It is a little known fact that many of the drug combinations we use today have never been tested in man. Further, patients might not disclose the use of psychiatric medications because of social biases toward psychiatric illness, or physicians, in their hurry to complete their 7-minute office visit, might fail to ask about psychiatric problems and medications.

Secondly, doctors have become pill-obsessed, too. All too often we don't take the time to refer our patients to qualified psychiatric or psychologic specialists. Instead, we try to add these drugs ourselves in the genuine hope of helping our patients with a "quick fix," perhaps not realizing all the consequences of our choice.

So maybe, just maybe, each of us can take a lesson from Michael Jackson, his "cardiologist" doctor, and others in a similar circumstance (

Anna Nicole Smith or Elvis Presley comes to mind). First, patients must disclose all of their medications to their doctors. Second, doctors need to exercise caution when any medication, especially psychotropic or sedative ones, are are added to our poly-pill-laden patients and consider the cardiovascular effects that could arise.

Doctors and patients who would like to know many of the medications suspected of causing cardiac arrhythmias, a relatively well-maintained list can be found from the University of Arizona at

qtdrugs.org.

-Wes