For reasons that escape me, Dr. Wes has found he has reached a period of critical blog block. I've had this happen before, and have survived it to blog another day. Other issues (like life) have taken their toll. I'll be back, but a blog break will do me some good.

In the meantime, when you think of Cheerios and the FDA, read this from a while back. Maybe the folks from the FDA will read it, too.

-Wes

Friday, May 29, 2009

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

How Health Care is Like GM

From Matthew Holt at the Health Care Blog:

-Wes

The parallels are obvious. In American health care policy, for the Big 3, substitute the AHA, PhRMA, AHIP, ADVAMED and the AMA. For the dumb carbon fuel policies, substitute an irrational employer-based insurance system with a wrap-around and uncontrolled Medicare and Medicaid system, all paying suppliers using Fee-For-Service. For the problems of global warming and pollution substitute the societal ill-effects of spending too much money on health care services that make outcomes worse, and leave less money for education, infrastructure and other more worthwhile spending. For SUVs and mini-vans substitute cardiology, orthopedics, neuro-surgery, general surgery, oncology drugs, and all the other service-lines that make hospitals profitable, but do very little for the overall health of the population. And of course the whole thing stays together because Congress is in the special interests' pocket, the public responds well to prods from special interests (especially doctors), and it doesn’t understand the raw deal it’s getting in the bigger picture.Read the whole thing.

-Wes

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Monday, May 25, 2009

Gray Papers and Health Care IT Cost Savings

If we want to see where the money in health care is going, look to the stock market. Cerner, one of the big players in health information technology, has seen its stock soar 50% so far this year, much of it from the federal stimulus package. This is part of the grand plan to save costs in health care, after all: why ask questions? If we just pour a few more billion dollars to health care information technology, we're sure to see lower costs, right?

So this got me wondering, where did this "cost-saving" mantra come from?

Much of it comes from the backing of a single 2005 Rand Corporation research “study” that concluded "if most hospitals and doctors' offices adopted [health-care IT], the potential savings for both inpatient and outpatient care could average over $77 billion per year."

So I had to look this study up. Who is the RAND Corporation? How was the study done? What measures did they use? Is this conclusion of $77 billion on cost savings realistic?

The RAND Corporation mission is "to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis." In other words, it is a political organization. Importantly, it's so-called "research" is funded from federal, state, and local government agencies provide the largest share of the funding; however, RAND also conducts projects for foundations, foreign governments, and private-sector firms. Contributions from individuals, charitable foundations, and private firms, as well as earnings from RAND's endowment, offer a steadily growing pool of funds that allow RAND to address problems not yet on the policy agenda. As they say, they're a "think tank." They THINK they are doing research, I guess.

Here's the "highlights." Big "studies", you see, need highlights. (Other more politically-minded individuals would call them "talking points," but I digress.) If one reads these highlights, we note that there is no "Limitations" section, a standard section of any reasonable research study that mentions reasons why a study's conclusions might not be valid. Nope. These conclusions are absolutes.

And I'm still looking for the funding "disclosures." Can anybody tell me who funded this particular "study?"

But a little digging and we find these "methods:"

But it doesn't stop there. It seems much of the basis of this data came from "gray literature" (their words, not mine) defined as "the body of reports and studies produced by local government agencies, private organizations, and educational facilities that have not been reviewed and published in journals or other standard research publications." Most of us would call these "white papers" produced by industry, but when their blended with one's own politically- or industry-supported research and cost savings are extrapolated to make a political point, the papers become "gray."

Recently, there has been a flood of "investigations" in to conflicts of interest between researchers, their academic institutions, and the medical device and pharmaceutical industries by Congress. But I find these supposedly "independent non-profit organizations," funded by industry members of the insurance, information technology and pharmaceutical industry including Unitedhealth, Wellcare, Aetna, Blue Cross of California, Genentech, Amgen, and Intel (to name just a few) more insidious and covert. They promulgate messages that are not peer-reviewed, but peer-pressed into the media, government, and create policy decisions that we assume (naively) are unbiased and truthful.

Baloney.

-Wes

So this got me wondering, where did this "cost-saving" mantra come from?

Much of it comes from the backing of a single 2005 Rand Corporation research “study” that concluded "if most hospitals and doctors' offices adopted [health-care IT], the potential savings for both inpatient and outpatient care could average over $77 billion per year."

So I had to look this study up. Who is the RAND Corporation? How was the study done? What measures did they use? Is this conclusion of $77 billion on cost savings realistic?

The RAND Corporation mission is "to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis." In other words, it is a political organization. Importantly, it's so-called "research" is funded from federal, state, and local government agencies provide the largest share of the funding; however, RAND also conducts projects for foundations, foreign governments, and private-sector firms. Contributions from individuals, charitable foundations, and private firms, as well as earnings from RAND's endowment, offer a steadily growing pool of funds that allow RAND to address problems not yet on the policy agenda. As they say, they're a "think tank." They THINK they are doing research, I guess.

Here's the "highlights." Big "studies", you see, need highlights. (Other more politically-minded individuals would call them "talking points," but I digress.) If one reads these highlights, we note that there is no "Limitations" section, a standard section of any reasonable research study that mentions reasons why a study's conclusions might not be valid. Nope. These conclusions are absolutes.

And I'm still looking for the funding "disclosures." Can anybody tell me who funded this particular "study?"

But a little digging and we find these "methods:"

The RAND team drew upon data from a number of sources, including surveys, publications, interviews, and an expert-panel review. The team also analyzed the costs and benefits of information technology in other industries, paying special attention to the factors that enable such technology to succeed. The team then prepared mathematical models to estimate the costs and benefits of HIT implementation in healthcare.Wow. Talk about a mish mash of data! I really have no worries now! Forget bias. Forget objectivity. Just throw everything in to a pot and, voilà, $77 billions of savings!

But it doesn't stop there. It seems much of the basis of this data came from "gray literature" (their words, not mine) defined as "the body of reports and studies produced by local government agencies, private organizations, and educational facilities that have not been reviewed and published in journals or other standard research publications." Most of us would call these "white papers" produced by industry, but when their blended with one's own politically- or industry-supported research and cost savings are extrapolated to make a political point, the papers become "gray."

Recently, there has been a flood of "investigations" in to conflicts of interest between researchers, their academic institutions, and the medical device and pharmaceutical industries by Congress. But I find these supposedly "independent non-profit organizations," funded by industry members of the insurance, information technology and pharmaceutical industry including Unitedhealth, Wellcare, Aetna, Blue Cross of California, Genentech, Amgen, and Intel (to name just a few) more insidious and covert. They promulgate messages that are not peer-reviewed, but peer-pressed into the media, government, and create policy decisions that we assume (naively) are unbiased and truthful.

Baloney.

-Wes

Sunday, May 24, 2009

Biking the Drive

Today, I participated in Chicago's 8th annual Bike the Drive where, for a brief five hours between 5 and 10AM, Lake Shore Drive is closed to traffic and folks from all over Chicago can see the city from one of it's most famous thoroughfares. Here's some pics:

It was a great time. Be sure to do it next year.

-Wes

More pics at the Chicago Tribune.

The start: head North or South? (We went North)

Looking back at Chicago from the Fullerton overpass.

The new Trump Tower from the Chicago River overpass.

Resting in the part after the ride.

And of course: breakfast! (Pancakes and yogurt)

Famous people were interviewed, like this little guy.

One of the better helmets I saw

It was a great time. Be sure to do it next year.

-Wes

More pics at the Chicago Tribune.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Friday, May 22, 2009

Tormented

There are some things that Electronic Medical Records do well and there are some things that Electronic Medical Records do poorly. To say that I need Electronic Medical Records to help me type is nothing short of ridiculous. Unfortunately, when engineers meet computer programmers and try to help health care professionals type in the health care record in the name of "safety," the results can torment those they're trying to help.

Take auto-spelling, for instance. I have the nasty habit of typing "Lungs: Claer to A&P" and marvel at the auto-correction feature automatically correcting my typing to "Lungs: Clear to A&P." This is an example of the wonders of electronics.

But when I type "DC Cardioversion" and the computer won't left me type "DC" because it wants to know if I mean "discharge" or "discontinue," the computer becomes intrusive, obstructive, and performs a service that should be right up there with water-boarding. I mean, is someone really going to mistaken that I mean "Discontinue cardioversion" or "Discharge cardioversion" when I'm typing my operative report? I could see this being a problem in the order-entry portion of the software, but when I'm typing by progress note or operative note?

Please.

Even better are the wonderfully useful letters "MS." These might mean "magnesium sulfate," "mental status," mitral stenosis, "MS Contin," "multiple sclerosis," "musculoskeletal," "Ms.," or maybe even "Mississipi." So, instead of being able to type a logical sentence without interruption, the doctor finds that that a drop-down pick list prevents those magic letters from being typed. It seems the chance that a nurse will wonder if you're prescribing a drug in a southern state trumps the ability to enter a simple sentence on the computer. This is, after all, how we're preventing medical errors.

But I wonder if these computer engineering road blocks are doing something much more insidious and detrimental to our health care delivery of tomorrow: like devaluing independent thought, reason, permitting the subtleties of context, and common sense.

No, better to torment instead.

-Wes

Take auto-spelling, for instance. I have the nasty habit of typing "Lungs: Claer to A&P" and marvel at the auto-correction feature automatically correcting my typing to "Lungs: Clear to A&P." This is an example of the wonders of electronics.

But when I type "DC Cardioversion" and the computer won't left me type "DC" because it wants to know if I mean "discharge" or "discontinue," the computer becomes intrusive, obstructive, and performs a service that should be right up there with water-boarding. I mean, is someone really going to mistaken that I mean "Discontinue cardioversion" or "Discharge cardioversion" when I'm typing my operative report? I could see this being a problem in the order-entry portion of the software, but when I'm typing by progress note or operative note?

Please.

Even better are the wonderfully useful letters "MS." These might mean "magnesium sulfate," "mental status," mitral stenosis, "MS Contin," "multiple sclerosis," "musculoskeletal," "Ms.," or maybe even "Mississipi." So, instead of being able to type a logical sentence without interruption, the doctor finds that that a drop-down pick list prevents those magic letters from being typed. It seems the chance that a nurse will wonder if you're prescribing a drug in a southern state trumps the ability to enter a simple sentence on the computer. This is, after all, how we're preventing medical errors.

But I wonder if these computer engineering road blocks are doing something much more insidious and detrimental to our health care delivery of tomorrow: like devaluing independent thought, reason, permitting the subtleties of context, and common sense.

No, better to torment instead.

-Wes

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Parsing Health Care Costs

I read Judith Graham's blog Triage in the Chicago Tribune this morning. It describes "three little stitches" that cost $900 for a patient that cut her finger using a kitchen knife and went to Sherman Hospital's "Urgent Care Clinic," rather than the emergency room:

But when we itemize the costs for for those stitches, where's the money going? Here's just a portion of the "costs" inherent to our current health care system:

All this for three little sutures at $300 dollars a piece.

Yes, this is what all this costs. In fact, it might be relatively cheap, given all the overhead that some insist continue with our current broken system.

Now, imagine another scenario (not that it will ever happen, especially now). But make no mistake, this is a time of disruptive change in health care. The real question is, which portions of the above costs will patients be willing to scrap in the interest of obtaining affordable health care?

-Wes

When the bill came, the amount initially seemed reasonable. The medical center charged her $383.40, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois paid $228.10. Rutke was left with a bill of $155.30.And now, doctors are seen as the bad guys.

But when a second bill arrived from Greater Elgin Emergency Specialists, Rutke blew a fuse. The doctor’s group that had attended to her at the immediate care center charged an additional $545.

But when we itemize the costs for for those stitches, where's the money going? Here's just a portion of the "costs" inherent to our current health care system:

- Facility costs

- Rent/mortgage/lights/security/phone/soap dispensers/restroom supplies, website, electronic medical record, etc.)

- State regulatory requirements

- Federal regulatory requirements

- Staffing costs:

- Front desk clerk (to assure proper demographics are entered to assure payment and perform initial triage)

- Nurse (to fill/refill prescriptions, evaluate post-operative wounds, dressing changes, etc.)

- Billing/collections staff (Assure proper billing/forms completion/credentialling of staff/manage accounts receivable/contact insurers/work denials)

- Doctor (ultimate responsibilty for care delivery - covers nights/weekends - must carry malpractice insurance)

- Insurers

- People to answer phone

- People to assure primary insurer pays their part (often Medicare) before the secondary insurer (them) pays theirs

- Managers to hire/fire workers, negotiate with hospitals/employers

- Senior managers and board members (who else will talk to the share-holders?)

- Suppliers

- Supplier of sutures, sterile supplies, pharmaceuticals (like local anesthetics), tetanus toxoid, and possibly antibiotics.

- Legal/Regulatory Fees

- Lawyers to draw up employment contracts, HR rules, Quality and Safety guidelines, defend litigation, etc.)

- Malpractice insurance

- Liability insurance

All this for three little sutures at $300 dollars a piece.

Yes, this is what all this costs. In fact, it might be relatively cheap, given all the overhead that some insist continue with our current broken system.

Now, imagine another scenario (not that it will ever happen, especially now). But make no mistake, this is a time of disruptive change in health care. The real question is, which portions of the above costs will patients be willing to scrap in the interest of obtaining affordable health care?

-Wes

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

The Exterminator

"I know an old lady who swallowed a fly. I don't know why, she swallowed that fly..."- An old children's folk song.

Hard to believe, but it happened again: another close encounter. But this time after a the last case of the day was completed. The photo documentation was made by a bystander's cellphone who looked on with such amazement that, well, it just HAD to be recorded for posterity:

Dr. Wes assesses the situation.

How does one reach the light where he's landed?

A little step here and a little step there to scale the cath lab table.

"It is locked, right guys?"

Approaching the prey with lethal baseball cap in hand.

(Hospital Safety/QA: note the careful spotting of Dr. Wes

by his carefully trained techician...)

Closer... closer... closer...

Success! (Damn thing was as big as a 747!)

"Uh, guys? Better call for a high clean!"

-Wes

Monday, May 18, 2009

Medtronic Issues New Pacemaker Advisory

Today, Medtronic began notifying physicians and patients about a new advisory (pdf) on some of their Kappa and Sigma series of pacemakers manufactured between 2000 and 2002. The defect stems from certain "voids" created in the solder joint where the attachments are made with the circuit board, causing them to fail over time. This loss of connection could lead to premature battery depletion, loss of rate response, loss of telemetry, or even no output.

Although these pacemakers were one of Medtronic's most popular pacemaker lines in early 2000-2004 with over 1.7 million devices implanted worldwide, it is estimated that only 36,900 remain actively implanted in patients. There have been two reported deaths that, while it is uncertain, may have stemmed from this problem.

According to the advisory letter, Medtronic has observed 285 Kappa devices and 131 Sigma devices affected by this issue, representing 0.49% of all Kappa devices and 0.88% of all Sigma devices implanted. It is estimated that the failure rates of Kappa pacemakers is 1.1% and Sigma pacemakers is 4.8% over the remaining lifetime of these pacemakers (the higher failure rate in the Sigma device because of its longer estimated longevity).

Physicians and patients can find if their particular device is affected by logging on to http://www.KappaSigmaSNList.medtronic.com to look up their specific serial number to see if it's affected by this advisory.

Also according to the letter, another subset of Kappa pacemakers involving an additional 96,000 devices might be affected by this defect, but at a much lower failure rate of 0.04% of the devices.

Physicians should consider replacing devices in pacemaker-dependent patients (those dependent on the device for their heart to beat). Further recommendations and information about the advisory can be found on the advisory letter issued today.

-Wes

Although these pacemakers were one of Medtronic's most popular pacemaker lines in early 2000-2004 with over 1.7 million devices implanted worldwide, it is estimated that only 36,900 remain actively implanted in patients. There have been two reported deaths that, while it is uncertain, may have stemmed from this problem.

According to the advisory letter, Medtronic has observed 285 Kappa devices and 131 Sigma devices affected by this issue, representing 0.49% of all Kappa devices and 0.88% of all Sigma devices implanted. It is estimated that the failure rates of Kappa pacemakers is 1.1% and Sigma pacemakers is 4.8% over the remaining lifetime of these pacemakers (the higher failure rate in the Sigma device because of its longer estimated longevity).

Physicians and patients can find if their particular device is affected by logging on to http://www.KappaSigmaSNList.medtronic.com to look up their specific serial number to see if it's affected by this advisory.

Also according to the letter, another subset of Kappa pacemakers involving an additional 96,000 devices might be affected by this defect, but at a much lower failure rate of 0.04% of the devices.

Physicians should consider replacing devices in pacemaker-dependent patients (those dependent on the device for their heart to beat). Further recommendations and information about the advisory can be found on the advisory letter issued today.

-Wes

The Confrontation

“You’re not going to kill me, are you?”

“No sir, we’ll take good care of you.”

“What?”

I shouted: “We’ll take good care of you!”

“Good. How many of these have you done?”

“At least two,” I shouted jokingly. “No, seriously, I’ve been doing lots of these since 1991. I honestly have no idea how many I have done.”

He smiled as he peered from behind the bed linens with warm, welcoming eyes. I could see his relatively thin chest and quietly wondered how large his vessel might be to accommodate the pacing lead.

“You better do a good job, you know I’d like to get home soon, not sure how much longer my caretaker’s going to want to feed the cat, and I have to make sure the company’s doing well.”

“If all goes well, from my standpoint you should be able to head home tomorrow.”

“Good. Now let’s get this done.”

And so, relucatantly, we did. What choice did I have? Gratefully, all went well.

In retrospect, this really isn’t much of a story …

… until you realize he was 101 years old.

-Wes

“No sir, we’ll take good care of you.”

“What?”

I shouted: “We’ll take good care of you!”

“Good. How many of these have you done?”

“At least two,” I shouted jokingly. “No, seriously, I’ve been doing lots of these since 1991. I honestly have no idea how many I have done.”

He smiled as he peered from behind the bed linens with warm, welcoming eyes. I could see his relatively thin chest and quietly wondered how large his vessel might be to accommodate the pacing lead.

“You better do a good job, you know I’d like to get home soon, not sure how much longer my caretaker’s going to want to feed the cat, and I have to make sure the company’s doing well.”

“If all goes well, from my standpoint you should be able to head home tomorrow.”

“Good. Now let’s get this done.”

And so, relucatantly, we did. What choice did I have? Gratefully, all went well.

In retrospect, this really isn’t much of a story …

… until you realize he was 101 years old.

-Wes

Saturday, May 16, 2009

The Truth, the Whole Truth, And Nothing But the Truth

The "Truth"

Peter R. Orszag, director of the White House Office of Management and Budget:

The "Whole Truth"

Robert Pear, journalist for the New York Times:

And Nothing But the Truth:

Peter R. Orszag, director of the White House Office of Management and Budget:

"... this week a stunning thing happened: Representatives from some of the most important parts of the health-care sector -- doctors, pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, insurers and medical-device manufacturers -- confirmed that major efficiency improvements in health-care are possible. They met with the president and pledged to take aggressive steps to cut the currently projected growth rate of national health-care spending by an average of 1.5 percentage points in each of the next 10 years. By making this pledge, the providers and insurers made clear that they agreed the system could remove significant costs without harming quality.

The "Whole Truth"

Robert Pear, journalist for the New York Times:

Health care leaders who attended the meeting have a different interpretation. They say they agreed to slow health spending in a more gradual way and did not pledge specific year-by-year cuts.

“There’s been a lot of misunderstanding that has caused a lot of consternation among our members,” said Richard J. Umbdenstock, the president of the American Hospital Association. “I’ve spent the better part of the last three days trying to deal with it.”

And Nothing But the Truth:

The Treasury had to revise its revenue estimates again earlier this week, as part of the final fiscal year 2010 budget submission for the Obama administration. The president’s initial February proposal for financing just half of his healthcare initiative’s reserve fund of $635 billion over the next decade came up a little short, upon further review by the fiscal referees upstairs in the booth. Obama’s original down payment for sweeping healthcare reform included a projected $317 billion from imposing a 28 percent ceiling on itemized deductions by Americans in the top two income tax brackets (where tax rates are higher than that figure). Treasury now calculates that this proposal would raise only $267 billion, or roughly 84 percent of the original projection.-Wes

Thursday, May 14, 2009

Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Meeting Quiet

Boston Convention Center May, 2009

Well, maybe the Heart Rhythm Society Meeting wasn't quite as bad as depicted in the above photoshopped image, but there's no question that attendance was lighter than I have remembered it in some time this year.

There were a number of factors for this: I am told a whole contingent of doctors from Japan were held back because of the lingering concerns of Swine flu. Then there's the fact that the Boston Atrial Fibrillation Summit was here earlier this past winter (who wants to travel to the same city twice?), and finally and perhaps most importantly, the recession. I met one nurse from Vanderbilt (Nashville, TN) who noted that all elective travel was suspended as a cost-saving measures in place. She only attended because she was paid to come and speak to a session for Allied Health professionals, effectively making her attendance at the meeting cost-neutral for her.

Now while this might not seem like a big deal, the implications to limiting continuing medical education to our health care team is concerning. But it's an easy thing to cut, right? After all, a penny saved is a penny earned. But what are the long-term implications for patient care if funds for continuing education are sacrificed? Certainly, if the downturn is brief, missing a meeting or two probably won't have much effect... or will it? Do we know?

And yet, despite this, the usual regiment of sales representatives for companies eager to get their face in front of doctors were ever-present. But the mood seemed muted, uncertain, as device companies were doing their best to stay upbeat despite the economic uncertainty. All were aware that Massachusetts, the home of the original North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (from which the Heart Rhythm Society morphed) and home of the current organization's president, will implement a law 1 July 2009 prohibiting medical device companies and pharmaceutical companies from courting their physician customers at these meetings. (No wonder the Heart Rhythm Society moved from Massachusetts to Washington, DC, eh?) While I understand the implications of the law, will this trend continue nationwide? Are medical conventions and doctor meetings as we've known them a thing of the past? Will we just meet online instead as the ultimate cost-saving trend?

Hopefully not. But it was not easy to see a definite change is occurring, and it's coming faster than we think.

Well, got to board the plane back to Chicago. See you back home soon.

-Wes

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

Heart Rhythm Society Meeting 2009

The Heart Rhythm Society's Scientific Sessions will kick off tomorrow in Boston, MA. This is where the latest and greatest ideas in heart rhythm management and research are shared. It offers valuable educational content, but also serves as a wonderful social backdrop to meet old friends and colleagues from around the world. It is here we reconnect, if ever so briefly. I'm not sure about the blog, the twittering, or whatever over the next few days since my stay will actually be very short this year - clinical coverage back home require it to be so.

But one thing I would like to see is a session entitled "Tales from the Unknown EPs" delivered by EP's who have never spoken at this conference around the country discussing their issues. It seems every year I go to this meeting, I always here from the same folks n similar topics. Not that they don't do a fine job, but it would nice to hear how common EP folks around the country are dealing with atrial fibrillation ablation at smaller institutions, or with their local cardiologists implanting defibrillators instead of them. Sessions like that can get pretty interesting! (heh, heh)

But we'll see what I can learn in the short two days I'll be there. I can never cover all the topics at a meeting this large, but if I find some new stuff, I'll be sure to share.

Cheers-

-Wes

But one thing I would like to see is a session entitled "Tales from the Unknown EPs" delivered by EP's who have never spoken at this conference around the country discussing their issues. It seems every year I go to this meeting, I always here from the same folks n similar topics. Not that they don't do a fine job, but it would nice to hear how common EP folks around the country are dealing with atrial fibrillation ablation at smaller institutions, or with their local cardiologists implanting defibrillators instead of them. Sessions like that can get pretty interesting! (heh, heh)

But we'll see what I can learn in the short two days I'll be there. I can never cover all the topics at a meeting this large, but if I find some new stuff, I'll be sure to share.

Cheers-

-Wes

In the Recession, Health Care is Not Immune

Big layoffs were announced today at Loyola University Medical Center:

The Loyola University Health System in west suburban Maywood Tuesday said it will cut more than 440 jobs, or about 8 percent of its work force, amid the recession and an economic downturn causing an influx of patients who cannot pay their medical bills.-Wes

For example, the number of patients who cannot pay their bills has increased by 73 percent the medical center's expenses on charity care to $31.3 million from $18.1 million for the nine-month period ended March 31.

The Making of McDonalds Medicine

It was interesting to see the response to free food offered by Oprah during her promotional stunt for Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC). For those unfamiliar with the situation, KFC wanted to market their new grilled chicken offering and enlisted Oprah to plug a free 2-piece meal for a limited time. To participate, Americans could download a coupon, print it on their computer, then come by their local KFC to receive their meal.

It was interesting to see the response to free food offered by Oprah during her promotional stunt for Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC). For those unfamiliar with the situation, KFC wanted to market their new grilled chicken offering and enlisted Oprah to plug a free 2-piece meal for a limited time. To participate, Americans could download a coupon, print it on their computer, then come by their local KFC to receive their meal.Well, the response was overwhelming: over a million people rushed to download Oprah's coupon offered online. They then sped on over to their local KFC with the coupon in hand during their lunch hour, only to encounter huge lines. After all, there were only so many people behind the counter to take the coupons, validate them, cook the food, and distribute the grilled chicken chunks to the masses. People got impatient. Lots and lots of people. So many people, in fact, that in store owners thought everyone must be xeroxing their coupons and giving them to friends, so soon they would only take the coupons printed in color. Shoving and expletives broke out. Frustration ruled. In short, it was a public relations nightmare.

So what does this have to do with health care reform?

Well, a lot.

After all, we're working on making medicine into McDonalds.

Think about it. We're in the planning stages of trying to build low-cost, highly affordable medical care for everyone. Not that this is necessarily a bad thing. I mean, who doesn't want cheap, convenient food once in a while? There will still be a pretty good selection of offerings: from the nutritious (like salads and apple slices) to the not-so-nutritious (like an occasional soft-served cone).

One thing's for sure, McDonalds will be busy. Very busy. After all, they don't call it "fast food" for nothing. We'll have to get used to that. Costs, after all, are key: keep 'em low. For the clever businessmen and businesswomen out there, opportunities for significant profit will still exist at our McDonalds health care of the future, at least for senior management. And for the suppliers, well, they'll do just fine, too since the demand will still exist for their services.

Soon we'll be ordering Combo Meal #1 after you suffer a Big Mac attack and receive our Big Mac, fries, soft drink included with follow-up care for a year for one low, low price! And if you want a sundae, you might have to pay a bit extra.

But if we take the analogy a bit further, who's going to be flipping the burgers? Who will be greeting the patients to take their order? Will we offer drive through services and be open late on weeknights and weekends? Will we hire cheap labor to keep our costs down? After all, what's there to flipping burgers and taking orders? Just take the order, enters them in the register, get the boys in back make the sandwich, and another mouth will be fed, all in just a few short minutes.

Whether or not we just have McDonalds or be able to step up to a Chipotle or Outback Steakhouse remains to be seen. Certainly for most, these options will do. But there will probably be a modest number of people for whom none of these options will do. For them, there will be a selection of five-star restaurants, but they'll have to pay for it themselves. Whether the government will permit doctors to work at these establishments is the question right now, since the mass exodus of physicians from burger flippers to something more palatable is seriously in question.

It sure is going to be interesting.

But America has spoken: McDonalds, please. And that's okay.

We just have to know what we're getting...

... and what the Combo Meals will cost us.

-Wes

Monday, May 11, 2009

Sunday, May 10, 2009

The Problems With the PolyPill

What if there were one pill that contained most of our drugs for managing coronary heart disease? We've already seen the marriage of antihypertensives with statins (a la Caduet). Why not add aspirin, too? But some point out there might be problems with this approach:

-Wes

But Washington Hospital Center cardiologist Patricia Davidson raises concerns: What would happen if patients react badly to one component of the pill or suffer some other negative side effect, the cause of which can't easily be identified?My feeling? The polypill is coming, despite doctors' misgivings, especially as the beleaguered pharmaceutical industry looks for new ways to repackage generic medications to make them look "new" again.

Aspirin, for example, causes bleeding in some individuals, but the problems caused by other drugs might be harder to identify. "It would be difficult to replace the three or four drugs when trying to eliminate the drug with the side effects," Davidson says.

Others have raised questions about the dosage levels of each of the ingredients in a single pill, which cannot be as readily adjusted to suit individual needs.

Beyond these concerns is a philosophical one: Should we expect a pill for every problem? Sure sounds good, as Robert Bonow recently pointed out at the American College of Cardiology annual meeting in Florida.

"A single pill," said Bonow, a professor of medicine at Chicago's Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University, "is exactly what people would love to have." But Bonow argues that medication should not be thought of as a means to "continue smoking . . . keep on eating what you're eating and not exercising."

-Wes

The Miracle of Mothers

...becomes obvious as you view this video viewed nearly 83 million times on YouTube. Seriously, try not to laugh:

Happy Mother's Day!

-Wes

Happy Mother's Day!

-Wes

Friday, May 08, 2009

Republican-Lite Health Care Policy

Kimberly Strassel over at the Wall Street Journal has a pretty good assessment of the Rebublican response to "Obamacare," as she calls it being proposed by Oklahoma Sen. Tom Coburn, MD, and North Carolina Sen. Richard Burr:

You gotta get a different angle, guys and unfortunately, time's running out.

-Wes

Their own bill overhauls the tax code, currently stacked in favor of corporate employees, to provide a tax credit to every American to purchase insurance. It expands health-savings accounts. It creates state health-insurance exchanges, where private insurers compete to cover Americans, including the uninsured. (This is partly modeled on the Medicare drug program, which has provided seniors with choice and held down costs.)And we wonder why this response falls on deaf ears. While much of their soon-to-be-ignored proposal has some merit, using prevention as a means of lowering costs is a straw dog: doctors know it, patients know it, and responsible politicians know it. Until our conservative members of Congress quit fooling themselves that American's really give a damn about the "prevention" Kool-aid and understand that prevention has never lowered health care costs (except, perhaps, seat belt laws and anti-smoking legislation), their proposal is doomed to failure.

More broadly, it seeks to reorient financial incentives so that the system is no longer focused, as Mr. Coburn puts it, on "sick care," but on preventing the chronic diseases that eat 75% of health expenditures. These incentives would be used to lower costs and discourage insurers from cherry-picking patients. The bill also dives into Medicare and Medicaid reform.

Yet no small number of Senate Republicans are biding their time in Max Baucus land, waiting to see what the Democratic finance chairman produces as a "bipartisan" product. (Read: A bill the president wants.) This crowd has taken to heart Mr. Obama's accusation that they are the party of "no," and think it might be easier to be the party of Baucus, or the party of Baucus-lite, or the party of nothing whatsoever.

You gotta get a different angle, guys and unfortunately, time's running out.

-Wes

Thursday, May 07, 2009

Man vs. Machine During CPR

Sometimes, even our best efforts to save lives fails us.

Sometimes, even our best efforts to save lives fails us.In an effort to minimize the time to deliver shocks in patients in cardiac arrest, hospitals across the country have turned to automatic external defibrillators to reduce the time to first shock, thereby improving cardiac arrest outcomes. More often than not, this policy has been effective at assuring that nursing staff and even locally-available non-medical personnel can at least treat a patient as soon as possible after a cardiac arrest.

But might there be an instance where the AED gets it wrong?

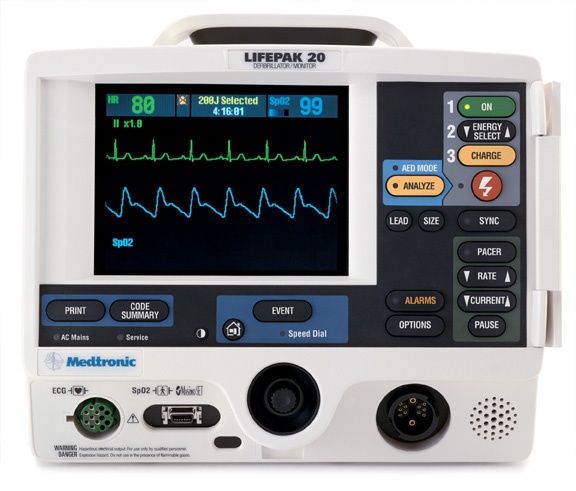

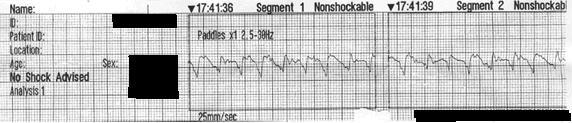

Well, of course. No shock algorithm is perfect. Take a look at this strip obtained from a Medtronic's Life Pak 20 defibrillator set to default to AED mode after a telemetry alarm prompted nursing personnel to rush to be patient's room, only to see the patient lose consciousness:

Click image to enlarge

CPR is started, but no shock was delivered. Why? Because the AED considered the rhythm "NONSHOCKABLE."

A quick call to the company suggests the algorithm (which is not published anywhere to my knowledge) involves five factors to attempt to be highly sensitive and fairly specific for ventricular arrhythmias: heart rate over 120, amplitude of the signal, slope of the received EKG morphology, QRS width, and something called "flat line content." Careful review of this rhythm demonstrates that it represents a heart rate over 120, is irregular, has varying QRS widths, and probably has different "slopes" and has an unknown "flat line content," whatever that represents.

While these findings are interesting for engineers, man (and women) must be allowed to intervene when it is perceived a machine is in error and anyone in a new, wide complex rhythm that causes a team of people to initiate CPR should consider the obvious:

Shock 'em anyway (synchronized to the QRS, of course).

Oh, and how do you deactivate the automatic nature of the AED on a Lifepak 20? Push any button besides the "Shock" button on the device and you'll be placed in manual mode.

-Wes

Wednesday, May 06, 2009

Plavix, Proton Pump Inhibitors, and Data Mining

This morning I was privy to a study that will be released in tandum with this blog post (I was sworn to secrecy by the PR firm that gave me a heads up about the results of the trial until 1:30 CST today). It's about another Medco pharmacy study that demonstrated inhibition of the platelet inhibitor clopidogrel (Plavix) with most of the currently-available proton pump inhibitors on the market: pantoprazole (Protonix), esomeprazole (Nexium), omeprazole (Prilosec), and lansoprazole (Prevacid). It seems they data-mined their pharmacy databases and looked for a combined endpoint (subtext: beware of data mining for "combined" endpoints - individual endpoints might not be as bad as the study suggests) compared the incidence of MI in people taking clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors to people taking clopidogrel alone, and a higher incidence of myocardial infarction was found.

As background, here's how the study was performed (from MedCo's press release (pdf)):

Now, is this evidenced-based medicine or correlationally-based medicine? Not that these data might not be important. But when we use medical claims data to guide medical treatment recommendations, as Medco seems to be suggesting, we tread on a potentially very slippery slope. For instance, the presence of "myocardial infarction" on a medical insurance claim may be there to assure payment for services rendered, rather than to identify a new heart attack. As such, claims data are notoriously poor at conclusively identifying clinical endpoints. Should physicians change patient's medication regimens based solely on datamining studies like this? Or would prospective randomized trials be more appropriate to make treatment recommendations? Can the claim that this interaction "increased hosptial costs by 40%" (as their press release claims) be substantiated? Or is this a means of marketing Medco's services to their clients, the largest of which might become the federal government?

It is interesting to note the rush to datamining as the United States implements rationing policies in the name of "personalized medicine." But we only have to harken back to the days of PVC suppression in my field where we thought that reducing PVC's must inherently be helpful at reducing sudden death risk. These assumptions started on the basis of correlational analysis. Only though a carefully-designed prospective, randomized trial (the CAST Trial) did we find the opposite was true: that antiarrhythmic medications designed to suppress PVC's actually increased mortality.

While general correlations are helpful to identify areas for future study, we have to be cautious not to leap to full blown treatment recommendations based on retrospective correlational studies derived from database mining alone.

-Wes

As background, here's how the study was performed (from MedCo's press release (pdf)):

The Clopidogrel Outcomes Study investigated medical and pharmacy claims data of 16,690 patients whoNo prospective data, mind you, but the results were "highly statistically significant."

were taking clopidogrel following a stent procedure and tracked the study subjects (editors note: using pharmacy and medical claims data) for a 12-month period from 2005 to 2006. The study compared a group of 6,828 patients who were concurrently taking a PPI and clopidogrel to a group of 9,862 patients who were only taking clopidogrel. When PPIs were examined individually, all of the associations were highly statistically significant.

Now, is this evidenced-based medicine or correlationally-based medicine? Not that these data might not be important. But when we use medical claims data to guide medical treatment recommendations, as Medco seems to be suggesting, we tread on a potentially very slippery slope. For instance, the presence of "myocardial infarction" on a medical insurance claim may be there to assure payment for services rendered, rather than to identify a new heart attack. As such, claims data are notoriously poor at conclusively identifying clinical endpoints. Should physicians change patient's medication regimens based solely on datamining studies like this? Or would prospective randomized trials be more appropriate to make treatment recommendations? Can the claim that this interaction "increased hosptial costs by 40%" (as their press release claims) be substantiated? Or is this a means of marketing Medco's services to their clients, the largest of which might become the federal government?

It is interesting to note the rush to datamining as the United States implements rationing policies in the name of "personalized medicine." But we only have to harken back to the days of PVC suppression in my field where we thought that reducing PVC's must inherently be helpful at reducing sudden death risk. These assumptions started on the basis of correlational analysis. Only though a carefully-designed prospective, randomized trial (the CAST Trial) did we find the opposite was true: that antiarrhythmic medications designed to suppress PVC's actually increased mortality.

While general correlations are helpful to identify areas for future study, we have to be cautious not to leap to full blown treatment recommendations based on retrospective correlational studies derived from database mining alone.

-Wes

Reworking Academic Medicine's Compensation Models

In these days of increased pressure on medical centers to maintain solvency, the days of the typical "sheltered workshop" of salary-based academic medicine are quickly coming to an end. With the uncertain terrain of health care reform looming on the horizon, paired with an economy that has hit the brakes, a new trend is sweeping academic medical centers: reworking compensation models for academic specialists that tie their doctors' "productivity" to conventional benchmarks published by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA).

Increasingly, program directors are under pressure to increase their divisions' revenues. Aggressive expansion plans initiated just before the market crash have put additional onus on centers to fund their growth plans since the ability to rely on cash reserves has dwindled. Academic medical centers have historically had more overhead costs than leaner private hospital systems and are increasingly turning to cardiology, orthopedics, radiology, and oncology services to make up their economic short-fall.

But should the MGMA data (which is based on productivity benchmarks from busy private practice groups or clinical hospital systems around the country) be used as an academic specialists' measure of productivity? How does one measure, based on MGMA data, the "value" of an NIH grant, writing a peer-reviewed article, performing clinical research, or teaching medical students? Is a clinical productivity benchmark based on the flawed RVU system the best way to measure academic productivity? What effect does using such a clinical benchmark have upon academic physician's behavior? Will using these benchmarks compromise medical student training as their teachers place increased importance to clinical productivity (carefully tracked by electronic medical records) over their teaching responsibilities?

These are perplexing issues for many academic centers, but increasingly, the term "pay for performance" no longer means simply "pay if your famous." Now, it's turning to "pay if you build volume." In that respect, if clinical research generates testing spin off (hence revenue), well then, it's okay. If the research is simply a cerebral exercise for the sake of advancing science, these days researchers are encouraged to reconsider.

Building a Compensation Model

There are two polar opposites of compensation models: (1) the "even-split" compensation model that assumes everyone does the same amount of work and therefore they should be paid the same, and the productivity, or "eat-what-you-kill" model. Each has their limitations.

For the even-split model, people must be comfortable with making the same income no matter how hard they work. In reality, people are never equally productive and the high producers inevitably cry foul when their less productive colleagues take more time off than they do but get paid the same. The "eat-what-you-kill" purely productivity model fails to engender cooperative efforts amongst the group and risks pitting doctors within the same group against each other as they work feverishly to assure their salary is secured. Initiatives that benefit the group as a whole are often ignored.

So which model to chose? Is there a compromise position?

Before leaping to a blend of the two systems, there are other considerations. For instance, how does a group compensate a person's efforts to grow business in a new market? Or how much value does the presence of a new research project have for the group? Will the compensation model permit enough time to work on the project? Also, how are subspecialists within a specialty compensated? In the case of a cardiology section, should those with nuclear imaging certification, interventional skills, or electrophysiology skills receive different pay for their skills? Finally (and perhaps even more importantly), what are the plans when people want to retire or leave the group? How would that be handled?

Finally, there's the issue of market-place compensation parity - especially in academics. Academic specialists often make less than private practice specialists because they do not typically own the equipment (and therefore can't garner the technical fees) that generates a significant portion of private specialists' revenue. If the salary differential grows too large between academics and private practice, what incentive would there be to continue academic medicine long-term? In the past, royalties and speaking engagements have offset these disparities. Now with Congress scrutinizing these arrangements and the potential conflicts of interest they invite, medical centers are increasingly turning to gain-sharing incentives to retain highly sought-after clinicians. But these incentives require clinical, measurable work to justify the additional compensation. Teaching and research simply have no markers for remuneration with that model. Look for these endeavors to get short shrift in the years to come.

Ultimately, it is up to each academic group to determine the best model for themselves. What is clear is that simple salary models are unlikely to fly any longer in today's highly competitive clinical health care market. Therefore, developing a transparent, workable compensation model is critical to maintaining some semblance of job security and satisfaction for the uncertain times ahead. Unfortunately, the days of sitting back on the laurels of one's academic credentials has left us long ago.

-Wes

Increasingly, program directors are under pressure to increase their divisions' revenues. Aggressive expansion plans initiated just before the market crash have put additional onus on centers to fund their growth plans since the ability to rely on cash reserves has dwindled. Academic medical centers have historically had more overhead costs than leaner private hospital systems and are increasingly turning to cardiology, orthopedics, radiology, and oncology services to make up their economic short-fall.

But should the MGMA data (which is based on productivity benchmarks from busy private practice groups or clinical hospital systems around the country) be used as an academic specialists' measure of productivity? How does one measure, based on MGMA data, the "value" of an NIH grant, writing a peer-reviewed article, performing clinical research, or teaching medical students? Is a clinical productivity benchmark based on the flawed RVU system the best way to measure academic productivity? What effect does using such a clinical benchmark have upon academic physician's behavior? Will using these benchmarks compromise medical student training as their teachers place increased importance to clinical productivity (carefully tracked by electronic medical records) over their teaching responsibilities?

These are perplexing issues for many academic centers, but increasingly, the term "pay for performance" no longer means simply "pay if your famous." Now, it's turning to "pay if you build volume." In that respect, if clinical research generates testing spin off (hence revenue), well then, it's okay. If the research is simply a cerebral exercise for the sake of advancing science, these days researchers are encouraged to reconsider.

Building a Compensation Model

There are two polar opposites of compensation models: (1) the "even-split" compensation model that assumes everyone does the same amount of work and therefore they should be paid the same, and the productivity, or "eat-what-you-kill" model. Each has their limitations.

For the even-split model, people must be comfortable with making the same income no matter how hard they work. In reality, people are never equally productive and the high producers inevitably cry foul when their less productive colleagues take more time off than they do but get paid the same. The "eat-what-you-kill" purely productivity model fails to engender cooperative efforts amongst the group and risks pitting doctors within the same group against each other as they work feverishly to assure their salary is secured. Initiatives that benefit the group as a whole are often ignored.

So which model to chose? Is there a compromise position?

Before leaping to a blend of the two systems, there are other considerations. For instance, how does a group compensate a person's efforts to grow business in a new market? Or how much value does the presence of a new research project have for the group? Will the compensation model permit enough time to work on the project? Also, how are subspecialists within a specialty compensated? In the case of a cardiology section, should those with nuclear imaging certification, interventional skills, or electrophysiology skills receive different pay for their skills? Finally (and perhaps even more importantly), what are the plans when people want to retire or leave the group? How would that be handled?

Finally, there's the issue of market-place compensation parity - especially in academics. Academic specialists often make less than private practice specialists because they do not typically own the equipment (and therefore can't garner the technical fees) that generates a significant portion of private specialists' revenue. If the salary differential grows too large between academics and private practice, what incentive would there be to continue academic medicine long-term? In the past, royalties and speaking engagements have offset these disparities. Now with Congress scrutinizing these arrangements and the potential conflicts of interest they invite, medical centers are increasingly turning to gain-sharing incentives to retain highly sought-after clinicians. But these incentives require clinical, measurable work to justify the additional compensation. Teaching and research simply have no markers for remuneration with that model. Look for these endeavors to get short shrift in the years to come.

Ultimately, it is up to each academic group to determine the best model for themselves. What is clear is that simple salary models are unlikely to fly any longer in today's highly competitive clinical health care market. Therefore, developing a transparent, workable compensation model is critical to maintaining some semblance of job security and satisfaction for the uncertain times ahead. Unfortunately, the days of sitting back on the laurels of one's academic credentials has left us long ago.

-Wes

Monday, May 04, 2009

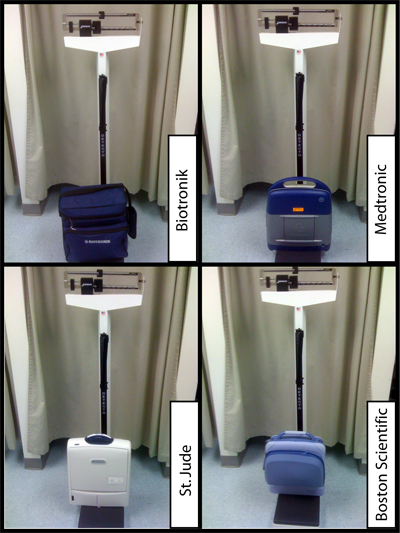

Pacemaker Programmers Weigh In

Anyone who has ever been on call for the Electrophysiology Service has to check a patient's pacemaker or defibrillator once in a while. To do this, we have to know which company manufactured the patient's pacemaker or defibrillator so we can grab the appropriate programmer that allows us to "talk" to the device in question. Often, these devices are lugged to far ends of the hospital, found to be the wrong device for the patient's particular device, dropped, or a small piece of the necessary equipment is left behind and must be retrieved. Suffice it to say, these devices get heavy after a while.

Since none of the companies have elected to standardize their process of pacemaker interrogation so the clinicians only have to lug one such device to a patient's bedside, they have left themselves open to public ridicule.

Soooooo, in the spirit of "friendly competition," I've decided to have the first ever "Pacemaker Programmer Weigh-In." Will it make them want to come together in the interest of patient care? Probably not, but it's fun to think it might get them thinking about such an endeavor again.

This was a carefully-conducted experiment, audited by PricewaterhouseCoopers (just kidding), and performed on our carefully-calibrated and zero'd cath-lab scale. Proof of the process is shown:

So, which manufacturer has the heaviest programmer and which has the lightest?

What's the range of weights?

-Wes

Since none of the companies have elected to standardize their process of pacemaker interrogation so the clinicians only have to lug one such device to a patient's bedside, they have left themselves open to public ridicule.

Soooooo, in the spirit of "friendly competition," I've decided to have the first ever "Pacemaker Programmer Weigh-In." Will it make them want to come together in the interest of patient care? Probably not, but it's fun to think it might get them thinking about such an endeavor again.

This was a carefully-conducted experiment, audited by PricewaterhouseCoopers (just kidding), and performed on our carefully-calibrated and zero'd cath-lab scale. Proof of the process is shown:

So, which manufacturer has the heaviest programmer and which has the lightest?

What's the range of weights?

-Wes

Rounds

What do I say to you when you open your eyes to me, blinking?

What do I say to you, as you stare to the right?

What do I say when you can only utter faint noises in response to my questions?

What do I say to you when I see those crumpled hands grasping the sheet below?

What do I say to you now that a triple-lumen catheter’s in your leg?

That pinned hip will help you now, won’t it?

Are you in pain?

Are you hungry?

Are you thirsty?

Are you warm enough?

How do I know?

What does one say, to a 96 year-old like this?

Helpless.

Clueless.

Not knowing not what to say.

Except, perhaps, I’m sorry.

-Wes

What do I say to you, as you stare to the right?

What do I say when you can only utter faint noises in response to my questions?

What do I say to you when I see those crumpled hands grasping the sheet below?

What do I say to you now that a triple-lumen catheter’s in your leg?

That pinned hip will help you now, won’t it?

Are you in pain?

Are you hungry?

Are you thirsty?

Are you warm enough?

How do I know?

What does one say, to a 96 year-old like this?

Helpless.

Clueless.

Not knowing not what to say.

Except, perhaps, I’m sorry.

-Wes

Saturday, May 02, 2009

eHarmonious.com

A hospital ad from the near future:

-Wes

* Folky music plays in the background *It's the new love affair: health care rationing via gain-sharing.

"Here at eHarmonious Health System, a national icon of cost-savings, we pre-screen each and every member based on oureligibilitycompatibility profile made up of 40 "action items" we have determined as bestpatientspractices.

Get started now with your Free Personality Profile, and we'll start matching you with other compatible health programs.

The best part is, you can review your matches absolutely free.

Aren't you curious who you'd be matched with?

Log on today, and review your eHarmonious matches for free.

eHarmonius dot com."

-Wes

Friday, May 01, 2009

Imaging Turf Wars

... between radiologists and cardiologists heats up in the Texas legislature as radiologists attempt to use financial transparency mandates to protect their turf.

-Wes

-Wes

Why I Left Government Health Care

My stint in the US Navy Medical Corps was a blast in many ways. I had the privilege of working with the finest men and women who worked tirelessly to improve the health and well-being of servicemen and servicewomen, their spouses, dependents, and retirees. It was a great place to get hands-on training: often it was "see one, do one." I never had to worry what a test cost back then. If I needed it, I ordered it. Occasionally there would be a radiologist who griped about performing a test late in the afternoon, but for the most part, there was a common mission, a profound sense of purpose, and a remarkably grateful group of people who appreciated what we did. And yes, there was the travel.

My stint in the US Navy Medical Corps was a blast in many ways. I had the privilege of working with the finest men and women who worked tirelessly to improve the health and well-being of servicemen and servicewomen, their spouses, dependents, and retirees. It was a great place to get hands-on training: often it was "see one, do one." I never had to worry what a test cost back then. If I needed it, I ordered it. Occasionally there would be a radiologist who griped about performing a test late in the afternoon, but for the most part, there was a common mission, a profound sense of purpose, and a remarkably grateful group of people who appreciated what we did. And yes, there was the travel.As a young military medical officer after medical school, I began my career when money flowed freely to the military health care system. The Viet Nam war was over for some time, but veterans were still plentiful from that conflict. There were many more bases open then since the downsizing movement had not started. We had very busy ward teams: three medicine teams of one resident and four interns, caring for about twenty to thirty patients each. Pathologies of all types were Medivac'd to our center all all hours of the day. The call team would see them and get each admitted, even late at night. Sleep came infrequently then. In short: it was hoppin'.

But over time, things changed.

It is interesting for me to recall my experience in the Navy as I ponder the implications of our push toward government-run health care. I mean, given my relatively positive experience with military health care, why would anyone want to leave such a system?

It certainly was not the people.

But after extensive years of training, it was clear that military doctors were significantly underpaid relative to our civilian counterparts. This is not to say that we did not fare well earlier in our training - we certainly did, making twice what the indentured servants of civilian residencies earn. But the lure of greener civilian medical pastures was a powerful incentive to leave the military, especially for specialists like myself.

Second, was what I called the Three O'clock Syndrome. Go to any military base in America and watch the stream of cars leave that base at 3PM every weekday. Three O'clock Syndrome. On military bases, most people are salaried. Overtime does not exist. People punched their ticket, did their job, then got the hell out of there. Best of luck to you if you needed something done after 3PM. Better to wait until the next morning.

Third, it was incredibly hard to remove non-military non-performers. The Human Resource rules regarding civil service employees were incredible. If you think unions are bad, think again. Civil service employees have even more safeguards to maintain their status quo. If you had a secretary that insisted that there were six digits in a phone number when you knew otherwise and wanted to fire him or her - best of luck. It wasn't going to happen. In the private sector - you don't perform, you're gone. With minor provisions, certainly. But gone.

Fourth, our entire military medical operation was beholden to Congress. If the money was too great, the system downsized. Considerably. That is how cost-savings occurs in the government. Witness the great military base/hospital shuttering that began in 1988 called the Base Realignment and Closure Act and was reinforced further in 2005. As would have it, military members (be they active duty or retired), often turned to civilian facilities for their care, and the inpatient military hospital patient census rapidly dwindled. ICU isolation rooms became nurses offices. As a doctor who knew things as they were, this was not a model that instilled a lot of confidence in the system of care for our military members and their retirees. Not that there aren't extremely capable people supporting our troops - there are - but the gradual deterioration of operations was obvious to those of us who had been there in more robust times. Finally, no matter how hard they tried to retain and recruit their doctors with "specialty bonuses" and "critical care bonuses," the military never seemed to be able to fill their demand for doctors.

I reflect on these experiences not to criticize the military health care system, but rather to offer a perspective of the real challenges we can expect as government bureaucracies take over the business of health care:

Outsourcing - this will occur when government facilities are filled to capacity. Look for private pay or secondary private insurers to pick up the slack - at considerable direct cost to the patient.Thankfully for me, I've been there before. For those not familiar with government bureaucracies to this magnitude, prepare to strap in. The adjustment will be harder for some than others. But one thing's for sure, it's coming. And if you would permit me one piece of advise I can impart that saved my butt more than once in the military, it would be this:

Shift work - Employees without economic incentives have little motivation to stay late, follow-through. Look for "hand-offs" of clinical care to accelerate. Continuity of care will occur by computer, rather than interpersonal connection.

Unionized workers - what other chance will workers have for bargaining against the government bureaucracy? Lone wolfs will simply not be heard.

Limitations to access - doctors will increasingly challenging to recruit. Facilities will be "reconfigured" and closed to save costs. As such, there will likely be increasingly long waits for care. But care will be available - really it will.

Equipment will still be state-of-the-art: after all, there will always be government contracts for which the private sector will continue to compete and schmooze members of Congress to fulfill. The equipment for the active duty military (though not always the VA hospitals I frequented), at least, was usually exceptional. It was finding the staff to run the equipment that was the problem. Look for this trend to continue.

Be sure to xerox everything you sign and keep a copy.

Why?

Because rest assured, the bureaucracy will lose it.

-Wes

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)