"Eventually, the cosmologists assure us, our sun and all suns will consume their fuel, violently explode and then become cold and dark. Matter itself will evaporate into the void and the universe will become desolate for the rest of time. ... (Read the rest)-Wes

Monday, August 26, 2013

On Sabbatical

I will be sparsely interacting with the internet as I take my last child off to college this week. It's a strange time - one where the home becomes more quiet as a moment ends for the parent yet heralds and exciting beginning for their child. Others have recently articulated this strange time well, so I leave you with the words of a much better writer, Michael Gerson of the Washington Post:

Saturday, August 24, 2013

The Cloudy Aspects of the Physician Payment Sunshine Act

Another seemingly harmless bureaucratic initiative aimed at physicians sunk its taproot deep in the daily workings of medicine this month. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act promises transparency in all industry dealings with physicians by shedding "light" on the issue of payments to physicians from pharmaceutical companies and medical device manufacturers. In turn, it will save the system money, since all those freebies bestowed upon physicians when the corporate world came knocking can now be accounted for and physicians will be shamed into proper behavior.

Meanwhile, back at the drug company headquarters, some poor schnook gets to type all the names of the nurses and technicians that enjoyed their meal from the echo lab, cath lab, stress testing lab and were asked to place their name on a sign-in list so it can be entered on a multi-million dollar database designed to feed the government Big Data Bosom in the sky. Busy doctors dart in, grab a bite, and go.

No need for them to sign-in.

You see, it's a bad marketing strategy to ask a doctor to sign a form as you peddle your product. And since no one is monitoring the accuracy of the sign-in sheets, as they have a few names to justify their effort and expense, well, they've done their part.

Why is this expensive data collection charade taking place? How much does it cost us? Does it change pharmaceutical tactics for marketing to doctors? Of course not. Yet there remain central planners who remain convinced (I mean, convinced!) that such monitoring works. It's a classic wish: just like the government's new HospitalCompare website, which promises to collect data on readmission, pneumonia, infection and death rates (with more to come) in the hopes that people will make "smart choices" about their health care. Do people really make their choice of health care facility based on such poorly-collected data placed on a website? I don't think so. Most people never think about their health until they have to arrive in an Emergency Room blindsided by an unexpected health crisis. They are not checking websites about payments to doctors - especially websites set up by the government. They want access to their local health care system and prompt, quality care. Yet were we are once again using Big Data filled with Bad Data as an ill-conceived and expensive social engineering exercise. And this cost is passed on to health care consumers. In short, it's another perfect storm of wasted resources in the practice of medicine.

"But Dr. Wes, how can you say such a thing? Can't you see this Sunshine Act developed by Congress as part of the Affordable Care Act will disclose all of those greedy physicians who want to suck the health care system dry of all of that money? Aren't there benefits to the public transparency of these payments?"

The irony of this whole law is that Big Pharma and Big Medical Device Company already reports the money they give doctors to the government via the IRS in the form of a 1099-Misc. (Recall that the IRS is now firmly a part of our new health care law). But instead of looking deep within the bureaucratic governmental morass for solutions to physician payments from industry, a new knee-jerk law was enacted to parade before the press to show how sincere the medical device companies and pharmaceutical companies are about the need for such transparency. Meanwhile, it's business as usual as backroom pricing of drugs and devices continues.

War room strategists have known this policy tactic for years: it's called diversion: collect data on every $20 dollar physician lunch handout as our new breed of physician-employers (aka "Accountable Care Organizations) negotiate sweet deals with their insurance pals, prices of hospital system charge masters edge ever higher, drug prices and device charges continue to exceed tens of thousands of dollars thanks to Medicare payments, and insurance companies offer "health plans" rather than "insurance" to their policy holders. And let's not even talk about the favors our Congressmen and Congresswomen are afforded.

But then again, better to put doctors in the limelight rather than speak honestly of the pricing games taking place behind American's backs, right?

-Wes

Meanwhile, back at the drug company headquarters, some poor schnook gets to type all the names of the nurses and technicians that enjoyed their meal from the echo lab, cath lab, stress testing lab and were asked to place their name on a sign-in list so it can be entered on a multi-million dollar database designed to feed the government Big Data Bosom in the sky. Busy doctors dart in, grab a bite, and go.

No need for them to sign-in.

You see, it's a bad marketing strategy to ask a doctor to sign a form as you peddle your product. And since no one is monitoring the accuracy of the sign-in sheets, as they have a few names to justify their effort and expense, well, they've done their part.

Why is this expensive data collection charade taking place? How much does it cost us? Does it change pharmaceutical tactics for marketing to doctors? Of course not. Yet there remain central planners who remain convinced (I mean, convinced!) that such monitoring works. It's a classic wish: just like the government's new HospitalCompare website, which promises to collect data on readmission, pneumonia, infection and death rates (with more to come) in the hopes that people will make "smart choices" about their health care. Do people really make their choice of health care facility based on such poorly-collected data placed on a website? I don't think so. Most people never think about their health until they have to arrive in an Emergency Room blindsided by an unexpected health crisis. They are not checking websites about payments to doctors - especially websites set up by the government. They want access to their local health care system and prompt, quality care. Yet were we are once again using Big Data filled with Bad Data as an ill-conceived and expensive social engineering exercise. And this cost is passed on to health care consumers. In short, it's another perfect storm of wasted resources in the practice of medicine.

"But Dr. Wes, how can you say such a thing? Can't you see this Sunshine Act developed by Congress as part of the Affordable Care Act will disclose all of those greedy physicians who want to suck the health care system dry of all of that money? Aren't there benefits to the public transparency of these payments?"

The irony of this whole law is that Big Pharma and Big Medical Device Company already reports the money they give doctors to the government via the IRS in the form of a 1099-Misc. (Recall that the IRS is now firmly a part of our new health care law). But instead of looking deep within the bureaucratic governmental morass for solutions to physician payments from industry, a new knee-jerk law was enacted to parade before the press to show how sincere the medical device companies and pharmaceutical companies are about the need for such transparency. Meanwhile, it's business as usual as backroom pricing of drugs and devices continues.

War room strategists have known this policy tactic for years: it's called diversion: collect data on every $20 dollar physician lunch handout as our new breed of physician-employers (aka "Accountable Care Organizations) negotiate sweet deals with their insurance pals, prices of hospital system charge masters edge ever higher, drug prices and device charges continue to exceed tens of thousands of dollars thanks to Medicare payments, and insurance companies offer "health plans" rather than "insurance" to their policy holders. And let's not even talk about the favors our Congressmen and Congresswomen are afforded.

But then again, better to put doctors in the limelight rather than speak honestly of the pricing games taking place behind American's backs, right?

-Wes

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

Why Do I Try So Hard?

It's always the same: It's the fifth hour of the procedure. As your ankles ache and the perspiration drips beneath your lead, you stand there wondering why you try so hard to fix this arrhythmia. You realize this is not cost effective. You're tying up the lab. The staff and anesthesiologist are getting restless. The music drones on. You feel you're not getting anywhere. "Then again, maybe if I just try this...," you think. And you try this and it fails. Meanwhile, the fluoroscopy clock ticks, your fight continues.

Then you remember the story: the syncope, the wife, the kids, the vocation. They're depending on you. Not a tech, not an anesthesiologist, not a nurse, not an administrator. You. So you keep going, just a bit longer.

And then, sometimes, miraculously, you win. It's all worth it. You've completely changed that person's life. You are the hero. You are the superstar.

But just as often, you have to quit. Your feet are too sore, the radiation dose too high, and the hour too late to safely continue. You have to face the family, the disappointed looks, the doubt about whether you were the right person to do this procedure, and the sad look on your patient's face when you break the news.

And you find yourself asking once again:

Why do I try so hard?

Why?

-Wes

Then you remember the story: the syncope, the wife, the kids, the vocation. They're depending on you. Not a tech, not an anesthesiologist, not a nurse, not an administrator. You. So you keep going, just a bit longer.

And then, sometimes, miraculously, you win. It's all worth it. You've completely changed that person's life. You are the hero. You are the superstar.

But just as often, you have to quit. Your feet are too sore, the radiation dose too high, and the hour too late to safely continue. You have to face the family, the disappointed looks, the doubt about whether you were the right person to do this procedure, and the sad look on your patient's face when you break the news.

And you find yourself asking once again:

Why do I try so hard?

Why?

-Wes

Friday, August 16, 2013

When Placing a Pacemaker, You Know You're on the Wrong Side When

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Heart Check Indeed: American Heart Association and Campbell Soup Company Sued

From Bloomberg:

Who's next? The Heart Truth® campaign, NHLBI, and the Coca Cola Company?

- Wes

Campbell Soup Company and the American Heart Association (AHA) were sued by a consumer who claimed the AHA fraudulently certifies the company’s products as healthy.Oh the irony, eh?

The association labels more than 30 of Campbell’s Healthy Request soups as “heart-healthy” even though a can has at least six times as much sodium as the organization recommends, according to a complaint filed yesterday by Kerry O’Shea in federal court in Camden, New Jersey. Those soups display the AHA’s “Heart-Check Mark” logo, which the organization licenses, according to the complaint.

Campbell, the world’s largest soup maker, and the heart association “falsely represent” that products with the logo have cardiovascular benefits lacking in other soups, according to the complaint.

Who's next? The Heart Truth® campaign, NHLBI, and the Coca Cola Company?

- Wes

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

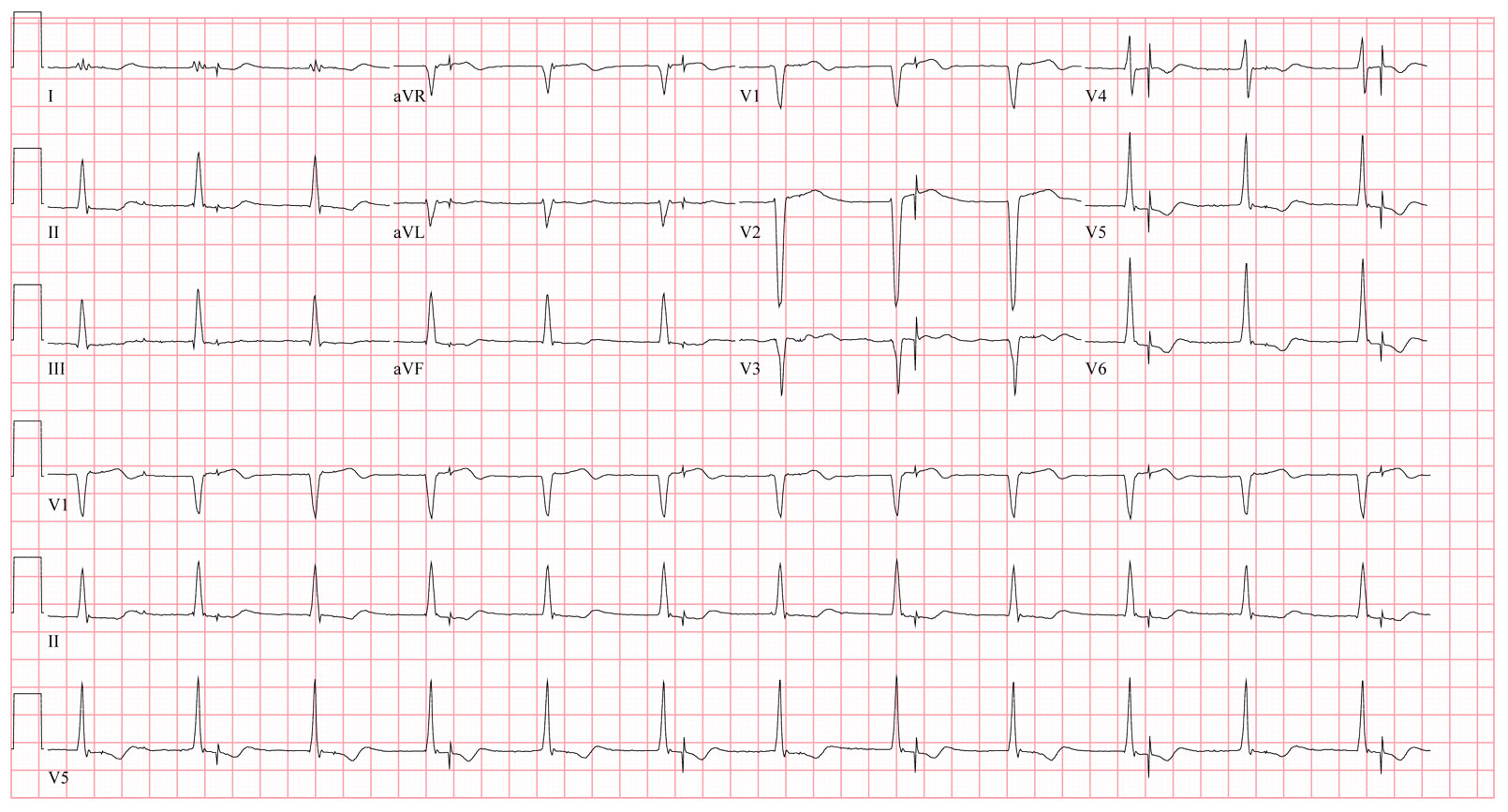

EKG Du Jour 32: The Misfiring Pacemaker

A dual chamber pacemaker was implanted the prior day by a local surgeon in the operating room. The next morning, an EKG is obtained that showed the following:

You checked the CXR and all leads appeared to be in the proper location.

Does the patient have to go back to the operating room? Why or why not?

-Wes

|

| Click to enlarge |

Does the patient have to go back to the operating room? Why or why not?

-Wes

Friday, August 09, 2013

Marketing Shared Patient Appointments

As health care reform kicks in to high gear, a new innovation in health care delivery is being touted at Cleveland Clinic: shared patient appointments. On the surface, this idea seems so efficient and social as patients with similar medical problems sit around in a group therapy session that masquerades as health care. After all, with the large influx of new patients to our health care system underway and the limited health care personnel resources available, the push for such a model was inevitable.

But many Americans are also noticing another disturbing trend: higher insurance premiums to offset the cost of those who do not have sufficient resources to pay for their care. While the reality of our higher health care costs demand that the added costs be paid by someone, I suspect most of those who will be paying higher premiums didn't think they'd have to "share" their physician appointments with others.

But here we are.

For large health care systems, shared patient appointments offer the promise of high revenue streams with low overhead costs. As such, there is no downside to promoting such a model:

Looking at this, how could anyone argue? It seems like such a helpful premise. But patients subjected to such a system have to agree one very important issue: surrendering their privacy:

-Wes

But many Americans are also noticing another disturbing trend: higher insurance premiums to offset the cost of those who do not have sufficient resources to pay for their care. While the reality of our higher health care costs demand that the added costs be paid by someone, I suspect most of those who will be paying higher premiums didn't think they'd have to "share" their physician appointments with others.

But here we are.

For large health care systems, shared patient appointments offer the promise of high revenue streams with low overhead costs. As such, there is no downside to promoting such a model:

Since 2005, the percentage of practices offering group visits has doubled, from 6% to 13% in 2010. With major provisions of the Affordable Care Act due to be implemented by next year, such group visits are also becoming attractive cost savers — patients who learn more about ways to prevent more serious disease can avoid expensive treatments. (ed's note: Sales pitch - there are no data that group appointments "prevent" more serious disease or "avoid" expensive treatments)

“It’s a different way of speaking about health that is more about friends around a circle learning together than talking with an authority figure in a white coat,” says Dr. Jeff Cain, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, in describing shared medical appointments. Think of them as a blend between group therapy and support groups. The net effect is the same – a sense of comfort, support and even motivation that comes from sharing similar experiences. (ed's note: Easy for him to say. Any proof?)

But they do require divulging and discussing private medical information in front of strangers (albeit ones who have signed waivers not to talk about other patients’ medical histories outside of the visit).

We should ask ourselves: how will assurances of patient privacy in such a setting be enforced? If another patient discusses a participant's health care needs and concerns outside of such a meeting, will that person be reprimanded? If so, how? And what extent must HIPAA privacy laws be waved as a result of this model?

These are only a few of the concerns for patients. We should also ask what the outcomes are for such a model? What value to patient's get for their health care dollar if another member of the group is more vocal and insists on speaking while others have to remain mute? Will they be guaranteed an opportunity to have their question(s) addressed? And how will patient's be selected for participation in these groups? Will diagnosis codes be used? If so, what happens (psychologically) to a group of early diabetics who are placed in a group with a diabetic with more extensive disease? Might there be negative repercussions when a young diabetic sits with a diabetic amputee or renal patient?

Efficient health care delivery models are needed going forward, but attempts at social re-engineering that can alienate some patients in favor of others and stands to profit a system rather than the individual demands careful evaluation before marketing such a model as gospel to our health care system.

-Wes

Saturday, August 03, 2013

A Case of Fraud

He was a slender-framed man, mid- to late-sixties, with a kind of ridden-hard-put-away-wet complexion. It was clear the years had not always been good to him, but being the kind soul that he was, he had plenty of friends. It was a beautiful summer day to spend with friends for a barbecue, but he arrived feeling puzzled why he collapsed at home earlier in the day.

He stopped at the keg and poured himself a beer in a red solo cup, and as he approached his friends with a smile, he did it again, this time which such gusto that his beer went flying and the thud he made when he hit the ground made everyone gasp. He laid motionless for a moment face down on the ground while his friends rushed to his aid. An ambulance was summoned as others rolled him over onto his back. He began to move - slowly at first - then more purposefully. As sirens approached, he asked his friends, "What just happened?'

A bit later, he arrived in the Emergency Room, awake, alert, pleasant, and seemed - on the surface at least - fine. His vital signs were normal - perfect, in fact. About the only things immediately noticeable was his thin frame, his coffee-stained teeth, and a clump of grass in his hair that the nurse kindly removed. He was placed in the gurney, an IV was started, blood was drawn, and EKG was performed as a few "hellos" and "what happeneds" were exchanged, then off to the CT scanner he went to rule out an intracranial process. It was normal and his EKG showed a first-degree AV block and incomplete left bundle branch block without evidence of acute injury or prior heart attack.

He returned from the CT scanner and was examined a bit more closely. A loud, blowing, holosystolic murmur was heard by the medical student. In fact, it was loud enough to create a "thrill" - a palpable vibration on the thin man's chest. The medical student seemed pleased with himself, then ordered his first echo which revealed a relatively weak heart with a few chamber walls that didn't move so well, and a very leaky heart valve. He was admitted, placed on telemetry, and seen by a cardiology consultant. Closer inspection of the echo revealed a dilated left ventricle with a posterior wall motion defect and a central jet of mitral regurgitation large enough to fill the left atrium with a mosaic of color that extended to the pulmonary veins. It was clear he'd need surgery, so a diagnostic catheterization was performed. It showed three-vessel coronary artery disease and confirmed severe mitral regurgitation. His medications were adjusted and surgery consulted. A date for surgery was arranged at the neighboring hospital the following week and all seemed well.

But he had different plans.

As he settled down for dinner, he felt suddenly flushed, lightheaded, and broke out in a sweat. With that, the telemetry alarm sounded and soon the room was full of people, crash carts, and hysteria. His dinner table was shoved aside and he was laid flat as his chest was made bare. He didn't know what all the excitement was about, but heard the words "He's fibrillating!" and then felt the cool metal discs covered with cold goo applied to his chest. "What are you do...?" and with that, he felt his chest and arms jerk violently just before he passed out. "Shit, he's still fibrillating!" someone shouted. So they charged again and shocked him, this time to sinus rhythm. The anesthesiologists who had arrived on the scene of the arrest took no chances: he was intubated and expeditiously transferred to the ICU.

Upon arrival to the ICU, the patient was clearly recovering well and quickly extubated the next day. Beta blockers were administered additional anti-anginal and anticoagulants given. Once stabilized, he was transferred to the surgical hospital and underwent urgent bypass surgery with mitral valve replacement. At the time, the surgeon could see considerable endocardial scar.

His recovery was uncomplicated, but four days after his surgery, he still required external pacing. Cardiac electrophysiology was consulted to consider an ICD placement, given his history of sinus node dysfunction, cardiac arrest, diminished LV function, and the visible presence of endocardial scar during surgery.

The electrophysiologist reviewed the case and noted that the patient's original in-house arrhythmia at the time of his "arrest" was actually an organized, rapid ventricular tachycardia that was then shocked into ventricular fibrillation by an asynchronous defibrillation attempt. An echocardiogram performed post-operatively showed a very low EF of 23%, but a good repair of his valve and he appeared to be progressing quite nicely in his cardiac rehabilitation. Still, it was felt he was at high risk for another arrhythmic event, so a wearable defibrillator as ordered as they waited out his conduction system a bit longer to see if it would recover function. It never did.

So 10 days later after the sinus node failed to recover, the electrophysiologist had a choice: implant a pacemaker, or implant a defibrillator? It shouldn't be a difficult decision in this case, should it?

But the electrophysiologist knew he'd be committing fraud if he implanted a defibrillator and billed Medicare for the device and procedure. That's because Medicare's 2005 National Coverage Decision requires doctors to wait 90 days and then "reassessing" the patient's heart function later before implanting a defibrillator once the heart is revascularized surgically.

But he wondered about the extra risk of infection created by two surgeries (one for a pacemaker and one later to upgrade the device to an implantable defibrillator) instead of one. He wondered if anyone ever considered the frequent venous occlusions that preclude later upgrade of pacemakers to defibrillators via the same side as the original pacemaker implant. Even if he implanted a defibrillator lead at the same time he implanted the original pacemaker, wouldn't he be committing fraud if a more expensive defibrillator lead were billed to Medicare instead of a pacemaker lead? And what about the added cost, inconvenience, and poor compliance rates of patients issued wearable defibrillators as they wait out the 90-day waiting period for an ICD? Finally, what are the ethics of asking his patient to sign a form that obligates the patient to pay for his defibrillator if Medicare fails to do so when the actual costs involved to implant a defibrillator are closely held institutional secrets?

So he wrote his note. He documented his rationale thoroughly.

Then proceeded to commit fraud.

-Wes

Refs:

Fogel RI, et al. The Ultimate Dilemma: The Disconnect Between the Guidelines, the Appropriate Use Criteria, and Reimbursement Coverage Decisions JACC, 2013;() doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.016.

Dr. Wes: When the Feds Come Knocking

He stopped at the keg and poured himself a beer in a red solo cup, and as he approached his friends with a smile, he did it again, this time which such gusto that his beer went flying and the thud he made when he hit the ground made everyone gasp. He laid motionless for a moment face down on the ground while his friends rushed to his aid. An ambulance was summoned as others rolled him over onto his back. He began to move - slowly at first - then more purposefully. As sirens approached, he asked his friends, "What just happened?'

A bit later, he arrived in the Emergency Room, awake, alert, pleasant, and seemed - on the surface at least - fine. His vital signs were normal - perfect, in fact. About the only things immediately noticeable was his thin frame, his coffee-stained teeth, and a clump of grass in his hair that the nurse kindly removed. He was placed in the gurney, an IV was started, blood was drawn, and EKG was performed as a few "hellos" and "what happeneds" were exchanged, then off to the CT scanner he went to rule out an intracranial process. It was normal and his EKG showed a first-degree AV block and incomplete left bundle branch block without evidence of acute injury or prior heart attack.

He returned from the CT scanner and was examined a bit more closely. A loud, blowing, holosystolic murmur was heard by the medical student. In fact, it was loud enough to create a "thrill" - a palpable vibration on the thin man's chest. The medical student seemed pleased with himself, then ordered his first echo which revealed a relatively weak heart with a few chamber walls that didn't move so well, and a very leaky heart valve. He was admitted, placed on telemetry, and seen by a cardiology consultant. Closer inspection of the echo revealed a dilated left ventricle with a posterior wall motion defect and a central jet of mitral regurgitation large enough to fill the left atrium with a mosaic of color that extended to the pulmonary veins. It was clear he'd need surgery, so a diagnostic catheterization was performed. It showed three-vessel coronary artery disease and confirmed severe mitral regurgitation. His medications were adjusted and surgery consulted. A date for surgery was arranged at the neighboring hospital the following week and all seemed well.

But he had different plans.

As he settled down for dinner, he felt suddenly flushed, lightheaded, and broke out in a sweat. With that, the telemetry alarm sounded and soon the room was full of people, crash carts, and hysteria. His dinner table was shoved aside and he was laid flat as his chest was made bare. He didn't know what all the excitement was about, but heard the words "He's fibrillating!" and then felt the cool metal discs covered with cold goo applied to his chest. "What are you do...?" and with that, he felt his chest and arms jerk violently just before he passed out. "Shit, he's still fibrillating!" someone shouted. So they charged again and shocked him, this time to sinus rhythm. The anesthesiologists who had arrived on the scene of the arrest took no chances: he was intubated and expeditiously transferred to the ICU.

Upon arrival to the ICU, the patient was clearly recovering well and quickly extubated the next day. Beta blockers were administered additional anti-anginal and anticoagulants given. Once stabilized, he was transferred to the surgical hospital and underwent urgent bypass surgery with mitral valve replacement. At the time, the surgeon could see considerable endocardial scar.

His recovery was uncomplicated, but four days after his surgery, he still required external pacing. Cardiac electrophysiology was consulted to consider an ICD placement, given his history of sinus node dysfunction, cardiac arrest, diminished LV function, and the visible presence of endocardial scar during surgery.

The electrophysiologist reviewed the case and noted that the patient's original in-house arrhythmia at the time of his "arrest" was actually an organized, rapid ventricular tachycardia that was then shocked into ventricular fibrillation by an asynchronous defibrillation attempt. An echocardiogram performed post-operatively showed a very low EF of 23%, but a good repair of his valve and he appeared to be progressing quite nicely in his cardiac rehabilitation. Still, it was felt he was at high risk for another arrhythmic event, so a wearable defibrillator as ordered as they waited out his conduction system a bit longer to see if it would recover function. It never did.

So 10 days later after the sinus node failed to recover, the electrophysiologist had a choice: implant a pacemaker, or implant a defibrillator? It shouldn't be a difficult decision in this case, should it?

But the electrophysiologist knew he'd be committing fraud if he implanted a defibrillator and billed Medicare for the device and procedure. That's because Medicare's 2005 National Coverage Decision requires doctors to wait 90 days and then "reassessing" the patient's heart function later before implanting a defibrillator once the heart is revascularized surgically.

But he wondered about the extra risk of infection created by two surgeries (one for a pacemaker and one later to upgrade the device to an implantable defibrillator) instead of one. He wondered if anyone ever considered the frequent venous occlusions that preclude later upgrade of pacemakers to defibrillators via the same side as the original pacemaker implant. Even if he implanted a defibrillator lead at the same time he implanted the original pacemaker, wouldn't he be committing fraud if a more expensive defibrillator lead were billed to Medicare instead of a pacemaker lead? And what about the added cost, inconvenience, and poor compliance rates of patients issued wearable defibrillators as they wait out the 90-day waiting period for an ICD? Finally, what are the ethics of asking his patient to sign a form that obligates the patient to pay for his defibrillator if Medicare fails to do so when the actual costs involved to implant a defibrillator are closely held institutional secrets?

So he wrote his note. He documented his rationale thoroughly.

Then proceeded to commit fraud.

-Wes

Refs:

Fogel RI, et al. The Ultimate Dilemma: The Disconnect Between the Guidelines, the Appropriate Use Criteria, and Reimbursement Coverage Decisions JACC, 2013;() doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.016.

Dr. Wes: When the Feds Come Knocking

Friday, August 02, 2013

Images of Change: The Patient Appointment

|

| Time Discarded |

Submitted as part of Image of Change: A Health Care Evolution Photo Contest. Feel free to submit yours (Instructions at the link). -Wes

Thursday, August 01, 2013

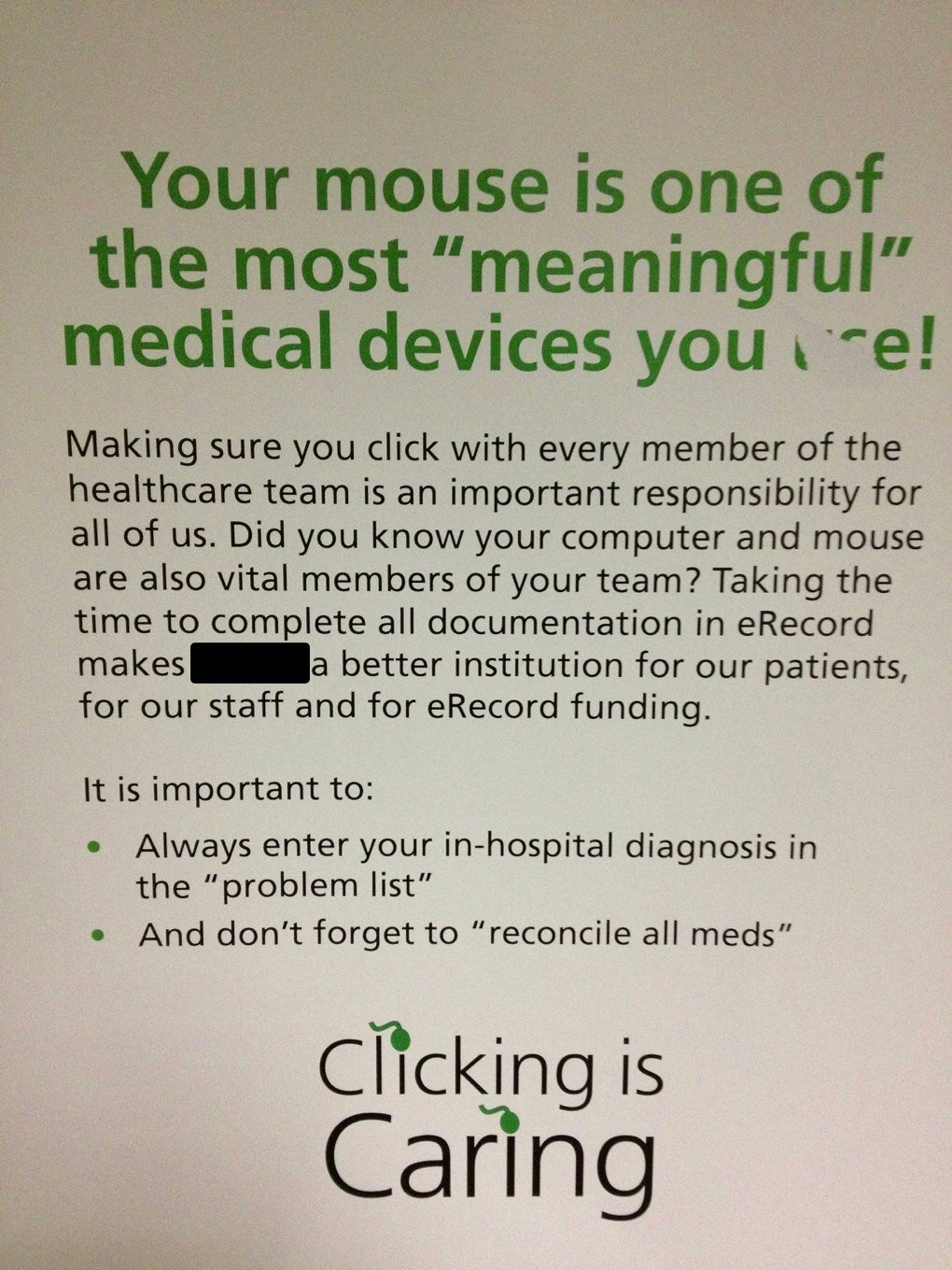

Images of Change: Clicking is Caring

Submitted as part of Image of Change: A Health Care Evolution Photo Contest. Feel free to submit yours (Instructions at the link). -Wes

|

| “The secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” - F. Peabody |

Submitted as part of Image of Change: A Health Care Evolution Photo Contest. Feel free to submit yours (Instructions at the link). -Wes

Images of Change: Going Private

|

| The Loss of Roommates, courtesy D. Graf |

Submitted as part of Image of Change: A Health Care Evolution Photo Contest. Feel free to submit yours (Instructions at the link). -Wes

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)