He had called the other day to update me up on his condition. He did not sound upset, but resolute. "They offered me peritoneal dialysis," he said, "but I decided against it and figured I'd just let nature take its course. The hospice people are so wonderful - I've got things all set here at home, but I have two questions. What should I do about my warfarin? You know, I just don't want to have a stroke. And what I do about my defibrillator?"

We were colleagues once and grew to be friends later when life's circumstances brought us together. He, a revered senior neurologist and me, a relatively new doctor in town. I could remember overhearing his heated discussions about administrative snafus with colleagues in the hall, or watching a horde of residents and medical students following him into a patient's room to teach at the bedside.

"Of course he didn't want a stroke," I thought.

So we decided to keep the coumadin and let him continue his daily INR checks at home and to turn off just the tachyarrhythmia detections on his biventricular defibrillator.

"I'll come over tomorrow and we'll turn it off," I said.

There was a brief silence, perhaps because of momentary disbelief that I'd do such a thing. Then he proceeded to give me detailed directions and landmarks to watch for on my way over. "I'm sure I can find it," I said thanking him.

So the next afternoon after most of the day's events had finished, I grabbed the programmer and drove to his home. It was an unusually beautiful day - mid 70's, sunny - as if Someone had wanted it that way. There in the yard, was his wife, wearing a large-brimmed hat and holding a hose while pretending to water the shrubs. She came over to greet me: "Thanks so much for coming over," she said, "I know this means so much to him." Then she realized she was still holding the hose. "Oh, I'm so sorry, it's just that someone has to try to keep the place up," she said, voice cracking.

The "place," of course, was beautiful. A majestic grande dame of a house - one I would later learn they had occupied for the past 44 years and bought when they were "just kids on the block." It was meticulousy kept, stately. I entered with his wife and noticed a shadowy figure two rooms away sitting at the edge of a mechanized hospital bed. The bed was placed in what must have been his study with a large bay window with a couch next to it. A reading lamp was over the head of the bed and the walls held books from the floor to ceiling with icons and statues, likely from other, more active time.

"Thanks for coming, Wes," he said, looking up.

"How are you feeling?" I asked, somewhat stupidly.

"Pretty good, considering everything. See? My legs aren't quite so swollen and my abrasions all have eschars on them," he noted as only a doctor could.

"Is there a plug nearby?" and he proceeded to point me the way so I could plug in the programmer to do my job while he explained the device to his wife. The process was quick and I interrogated his defibrillator, then turned off the tachyarrhythmia detections, therapies and now needless alarms. "There, that didn't take long. All done," I said.

There was a moment of silence as I sat with this man whom I known for so long. Like a wise sage and hospitable host, it was clear he wanted to talk for a bit, so I slowed my exit.

"You know, I've always appreciated your frankness about my condition," he said. "You're a lot like me in many ways, I think. You never overstepped, let me have control, to manage things like I wanted to, and I've always appreciated that," he said.

Embarassed by his frankness, I wondered what to say. At a loss for words, I told him how much I enjoyed meeting his family, wife, daughters, and grand-daughters recently in the hospital. He looked puzzled, forgetting. "You know, that day I brought my daughter in your room with them?" His eyes brightened and his smile widened as he remembered.

"Oh, yes! That was wonderful! How fast times flies, doesn't it?" he said.

"You know, I wrote about that day in my blog," I mentioned, ".. and included some pictures of my daughter from 10 years ago - about what she thought about medicine - can I show you?"

"Of course!"

So I showed him the picture and we shared our thoughts about family. Then, to make reading from my iPhone easier, I read him the post I'd written about that day. We talked about family and what they meant to each of us. And then he shared with me another nugget, that he grew to become a writer, too.

"You know, I spent some time and wrote an autobiography for my kids not too long ago - over a hundred pages - about everything I could remember - from my earliest years as a child, about my immigrant father and American mother. My father made it as a successful lawyer - came over from eastern Europe - I even know the ship - I remember the picture of him standing there with his hat..., and I wrote about my family, influential teachers in grade school, fellow professors, and people that I knew throughout the years - everything. You should do that, too, you know. I'm so glad I did. I gave them to my kids and even made some some extra copies - maybe for the grandkids, in case they want it someday..." He looked away to see his wife leave the room, trying not to be noticed as tears filled her eyes once more. She didn't want to him to see her this way.

He stared down at the floor beneath his swollen feet, then continued.

"You know, it was therapeutic for me to write that autobiography. After all, what we do is terribly isolating for the most part. No one understands that. Like you do your procedural stuff and I do my diagnosing. We do most of it all alone, with no one else there. Just the patient and the doctor. Wonderful, to be sure, but isolating. So many memories. I guess it helped me to put some of those feelings and the thoughts I had about those I loved into words. It's hard to capture it all..."

He looked up from the floor and stared in my eyes. "Thank you," he said extending his hand.

I sat motionless for a bit digesting the gravity of his words, lost in them before I saw his hand. Once I noticed, I lept up to shake it and gave him a long hug to his increasingly skeletal frame. It was a brief moment to share together once more and one I now realized I had done too infrequently with other patients in a similar circumstance. Here he was, an incredible man who'd given so much to his family, fellow colleagues and patients, now teaching me once more so much about life as a doctor, about grace, and about real love. Just the two of us, isolated again, but as friends.

With great reluctance I packed things up and found his wife on my way out. "Thank you," she whispered with swollen eyes, "I just don't want him to be in pain."

"He's going to be fine," I told her, "... perfectly fine, especially now. He's such a wonderful guy." She smiled and opened the door.

As I drove away I realized we probably won't see each other again - his remaining time here will be saved for others now. There were so many thoughts, so much to remember, so much still to learn. Perhaps because I'd been through something like this before I was more prepared - it's never easy - but I still felt okay about it all - not sad - confident that we did the right thing...

... together.

-Wes

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

Time Lapse: Pacemaker Implantation Table Setup

Oh, the wonders of Apple's iOS8! Now there's no excuse for slow room turnovers:

Yeah, I can see all kinds of applications for time lapse photography, especially when it comes to improving my productivity...

-Wes

Yeah, I can see all kinds of applications for time lapse photography, especially when it comes to improving my productivity...

-Wes

Friday, September 19, 2014

Case Study: What They Don't Teach You in EP Fellowship

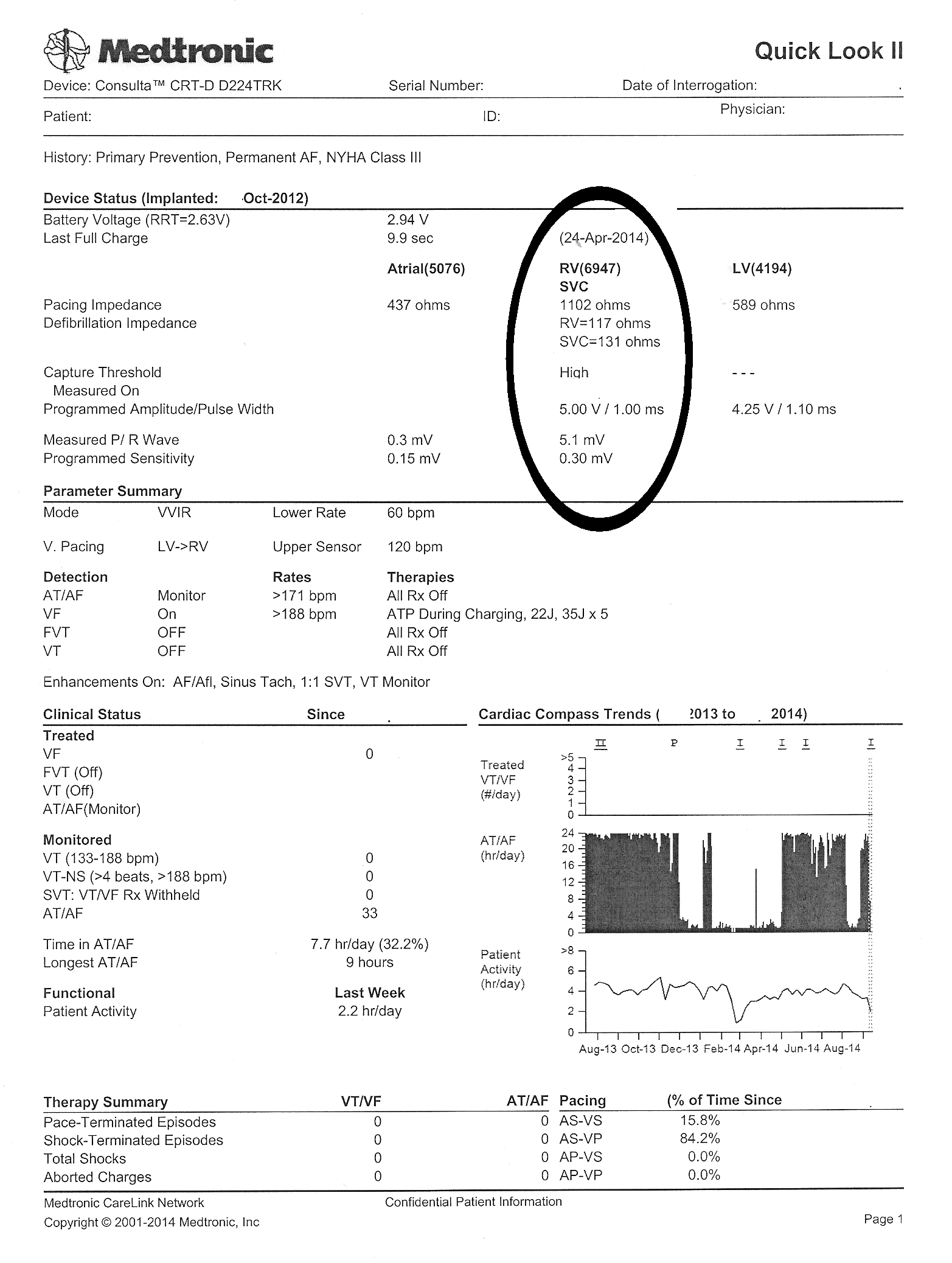

These days, pacemakers and defibrillators are often interrogated via a home-monitoring system that uploads information contained in the implanted cardiac devices automatically to a central server so it can be accessed by physicians remotely. This feature was added to most defibrillators after the rash of recalls struck the industry in 2005-6. Not only can the information be uploaded electively by the patient, it can also be automatically uploaded if a nightly self-check detects a parameter out of range. In this case, the patient was being monitored by Medtronic's Carelink remote monitoring system.

"Dr. Fisher, I think we have a problem with Mr. Smith's RV lead (not his real name)," my device nurse said as she handed me the Carelink transmission that triggered an superior vena cava (SVC) high voltage coil impedance warning:

|

| Click to enlarge |

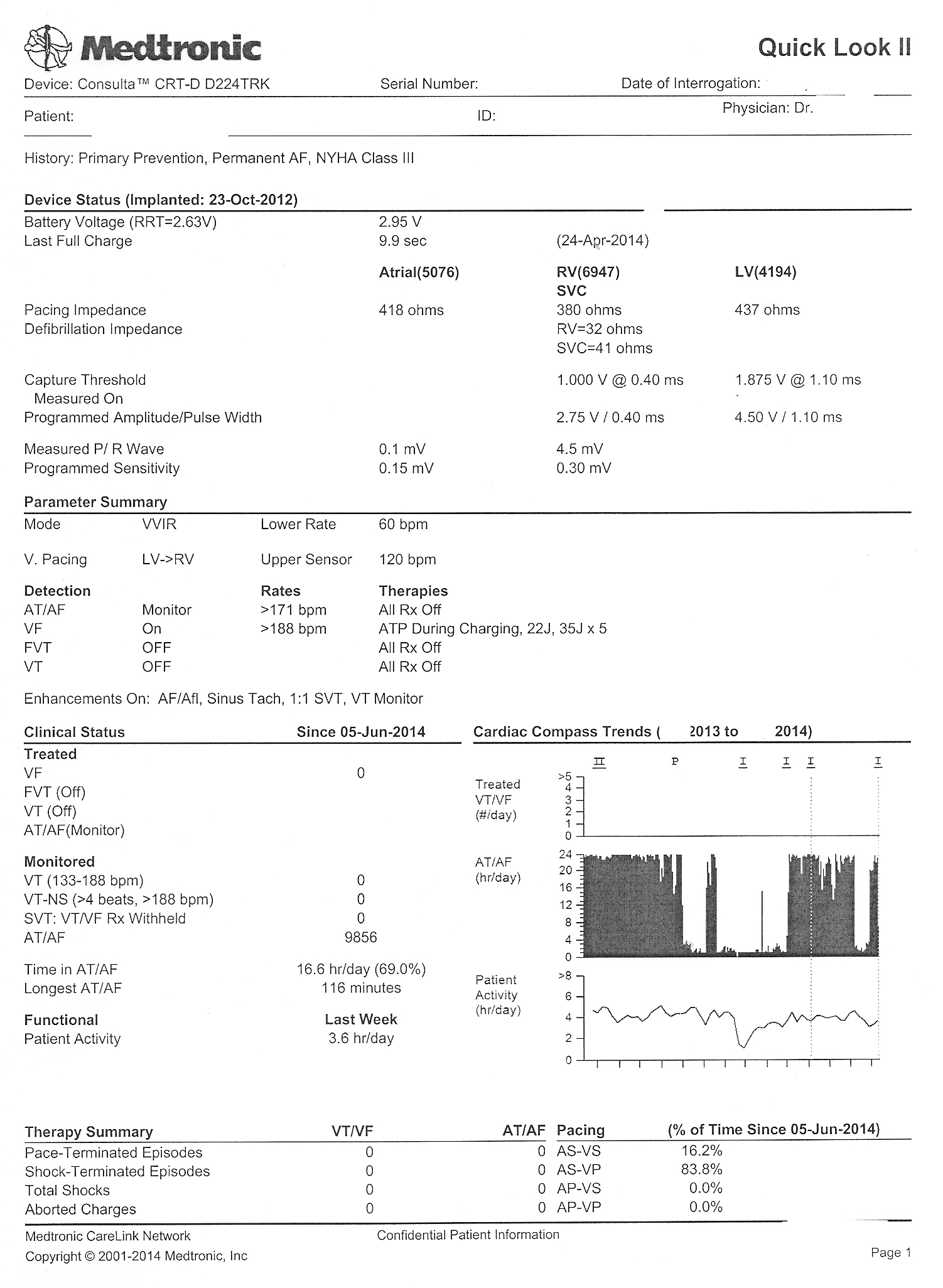

"What did the last interrogation look like?" I asked.

"Here's the old one was sent just three days before and looked fine," she said. "It's so weird. We've not had a problem with this patient's device since it was implanted in 2012."

|

| Click to enlarge |

|

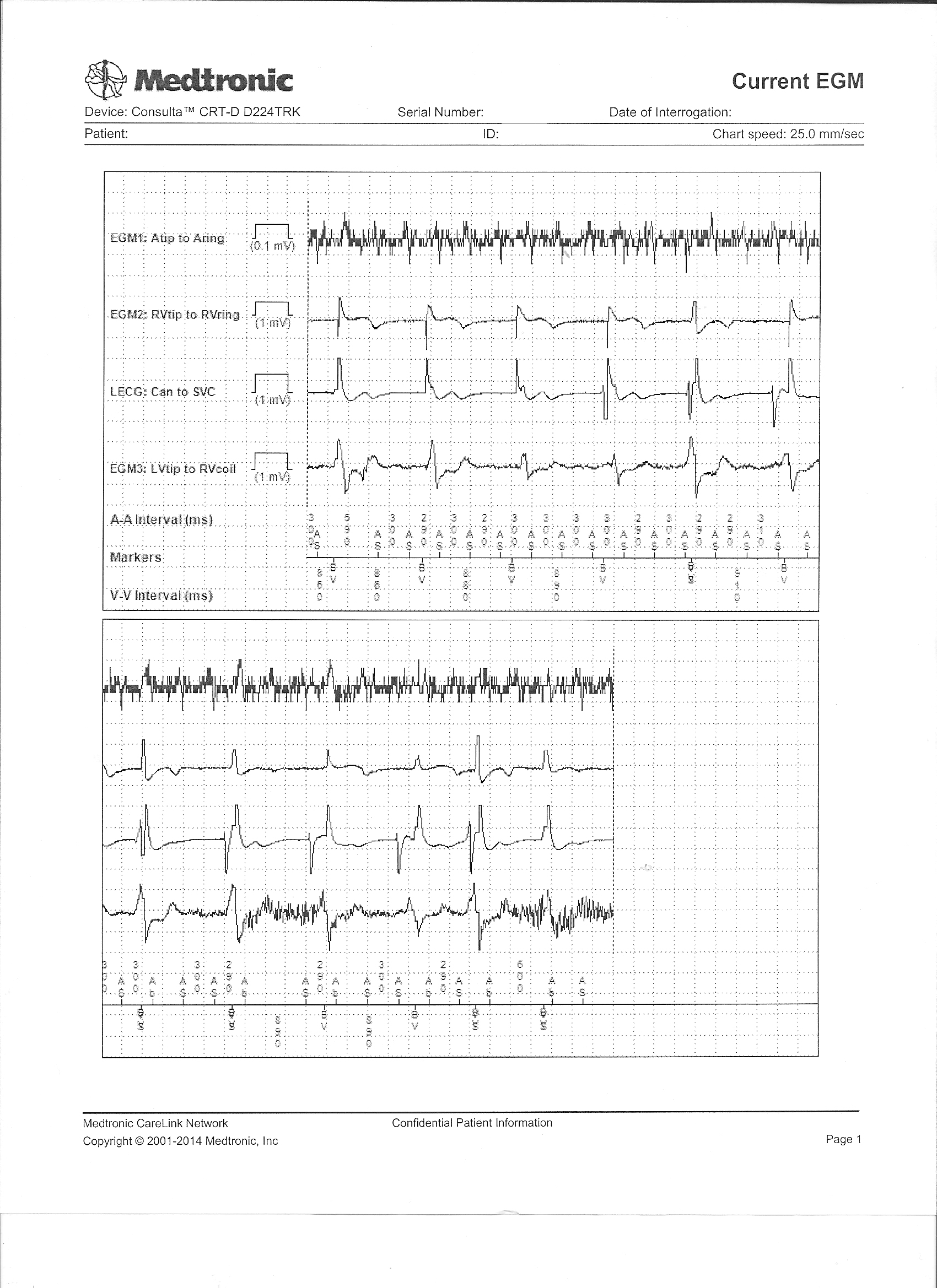

| Real-time intracardiac electrograms seen on the earlier transmission - Click to enlarge |

"Strange. I'm not sure what to make of this. Give him a call - we might have to change that RV lead," I said.

"Okay," she said, then returned to the device clinic and I went back to seeing patients.

Some time later, my nurse returned.

"Um, Dr. Fisher, could I speak with you a moment?" she asked. "I got some more information. I think you better look at this" and she handed me his most recently transmitted real-time intracardiac electrogram recording that was sent with the latest transmission.

What did it show and why were the RV lead parameters abnormal?

-Wes

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Rebuttal: A Bit More on MOC Failure Rates

Recently, David H. Johnson, MD, Chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Board of Directors and Internal Medicine Chairman at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, and Rebecca Lipner, PhD, Senior Vice President of Evaluation, Research, and Development at the ABIM published a "guest blog post" over at MedPageToday regarding Maintenance of Certification (MOC) pass rates, entitled "Debunking the MOC Pass Rate Myths." I do not know if they were directing their comments directly to me, but since I was the one who brought the issue of rising MOC failure rates to the public's attention some time ago using the ABIM's own published data of first-time MOC takers, I thought I should respond.

I appreciate Drs. Johnson and Lipner providing more insight into how the MOC examinations are constructed and scored. The ABIM's arbitrarily-defined "65%" marker based on "expert consensus" and undisclosed "psychometrics" is an interesting one, and at least now we understand how this benchmark was arbitrarily created. They also acknowledge that "significant changes in the practice of the discipline may require that the passing standard be reset." Unfortunately, they do not disclose what those changes might be, which way their 'standard' might be adjusted, or what internal or external force might mandate such an "reset."

Drs. Johnson and Lipner also confirmed the rising failure rates of board examinations over the past five years. Oddly, they then seem to imply that this "decline in pass rates" is due to a misunderstanding by "some social media observers" of their testing and scoring process:

Drs. Johnson and Lipner also remind us that "pass rates are higher among first-time test takers." While there are likely many reasons for this, we must conclude that significant AGE BIAS against older, more experienced physicians exists. Since this proprietary MOC process was cleverly made a "quality measure" imbedded in our new health care law, the logic of this biased process contradicts common sense. Are patients not our best teachers? Are we to assume that physician experience after years of direct patient care is of less value than ABIM-selected facts and principles culled from an exponentially-growing body of medical literature regurgitated on a computer screen in an expensive testing center? Furthermore, how the test is constructed or scored is of little relevance to more procedural based specialties of internal medicine like mine because these skills are never assessed.

Drs. Johnson and Lipner also mention (without supporting data) that physicians who take their examination three times (at their expense) ultimately achieve a 95% pass rate. As if this is the point. Instead, we should ask what patients and physicians lose each time they must repeat this onerous, time-consuming and unproven process. Can the personal, financial and professional losses of repeated testing ever be regained? How, exactly, does repeated testing of a flawed process help our patients? What marginal utility to our health care system does this whole test-taking exercise really provide? Does this MOC process actually separate the good physician from the bad physician or the good test-taker from the bad one? Since ABIM never knows a doctor's scope of practice before their assessment, they make some heady assumptions about what they should test. In reality, the ABIM only tests what THEY think should be tested, rather than what matters to the particular physician's patient population. Worse still, since the ABIM remains completely unaccountable to doctors or patients in regard to their MOC process, their assessment may have absolutely no relevance to a particular physician's practice. Shouldn't we be discussing these issues before arguing how the test is constructed and scored?

No physician I know argues with the need for continuing, life-long education in medicine, especially when its performed in a relevant, transparent, informative, collegial and feedback-oriented process without a ulterior financial motive. If fact, most of us do this every week as part of our state licensure requirements and have plenty of continuing medical education credits to prove it. Allowing the ABIM to monopolize this process as we have through artificial MOC point acquisition exercises that are often irrelevant to a physician's scope of practice not only circumvents more healthy and sustainable learning environment, but also might cause more harm than good if that physician loses their practice privileges as a result.

In summary, I believe the ABIM's lucrative MOC process is no more valid than what doctors have already been doing for years before the American Board of Medical Specialties decided to make their MOC program an annual exercise. The MOC process remains unproven in its ability to improve patient care and (as we've now confirmed) discriminates against more senior physicians. Those of us who have endured this process multiple times have witnessed the growth of "board certification" from a self-imposed professional milestone to a money-making scheme filled with clinically-irrelevant busywork that often detracts, rather than augments, patient care (especially those non-validated "practice improvement modules").

It is time that doctors of all ages insist that these self-appointed non-profits organizations cease their attempt to become expensive continuing education providers and stick to what they do best: assessing a doctor's ability to reach a level of exceptionalism of their practice during their career, rather than pretending that they can assure some arbitrary level of ongoing practice adequacy for the business community. Until the ABIM comes to grips with their increasingly bipolar agenda, their ability to remain credible and relevant to practicing physicians, the public, and the mysterious "stake holders" they claim to serve will continue to be challenged, both on social media and in the court of law, as "significant consequences from losing certification" occur with increasing frequency to experienced and fully-capable physicians.

-Wes

I appreciate Drs. Johnson and Lipner providing more insight into how the MOC examinations are constructed and scored. The ABIM's arbitrarily-defined "65%" marker based on "expert consensus" and undisclosed "psychometrics" is an interesting one, and at least now we understand how this benchmark was arbitrarily created. They also acknowledge that "significant changes in the practice of the discipline may require that the passing standard be reset." Unfortunately, they do not disclose what those changes might be, which way their 'standard' might be adjusted, or what internal or external force might mandate such an "reset."

Drs. Johnson and Lipner also confirmed the rising failure rates of board examinations over the past five years. Oddly, they then seem to imply that this "decline in pass rates" is due to a misunderstanding by "some social media observers" of their testing and scoring process:

"Recently, based on a slow decline in pass rates over the past 5 years for the American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification exam, some social media observers have made erroneous assertions about how the exams are constructed and scored.Rather than attack what was said or what wasn't by those unruly social media types, I will merely say this: my assessment of the rising failure just focused on simple math. Because there are higher numbers of doctors taking this examination year after year due to the American Board of Medical Specialties' recently-imposed MOC requirement, the stable "65%" pass rate means there is necessarily an INCREASE in the number of total physicians who are FAILING the examination. It goes without saying that a requirement for repeated testing or adding more people to the testing pool handsomely profits the ABIM and similar subspecialty organizations that provide proprietary subspecialty MOC-preparation courses taught by ABIM test question contributors (this relationship is also conflicted, by the way). But the downside of more testing is multi-pronged: it also redirects physicians away from direct patient care to formal classrooms, expensive hotel meeting rooms in cities often outside the physician's hometown, and ultimately to expensive corporate test taking centers. The ABIM never considers these high costs nor the negative effects absence from one's practice has on patients or a physician's limited family time.

Without a full understanding of the exam process, they have nevertheless claimed that the exam is being made more difficult, that the standard for passing the exam changes every time an exam is given, or that the exam is 'graded on a curve.' These assertions are all incorrect."

Drs. Johnson and Lipner also remind us that "pass rates are higher among first-time test takers." While there are likely many reasons for this, we must conclude that significant AGE BIAS against older, more experienced physicians exists. Since this proprietary MOC process was cleverly made a "quality measure" imbedded in our new health care law, the logic of this biased process contradicts common sense. Are patients not our best teachers? Are we to assume that physician experience after years of direct patient care is of less value than ABIM-selected facts and principles culled from an exponentially-growing body of medical literature regurgitated on a computer screen in an expensive testing center? Furthermore, how the test is constructed or scored is of little relevance to more procedural based specialties of internal medicine like mine because these skills are never assessed.

Drs. Johnson and Lipner also mention (without supporting data) that physicians who take their examination three times (at their expense) ultimately achieve a 95% pass rate. As if this is the point. Instead, we should ask what patients and physicians lose each time they must repeat this onerous, time-consuming and unproven process. Can the personal, financial and professional losses of repeated testing ever be regained? How, exactly, does repeated testing of a flawed process help our patients? What marginal utility to our health care system does this whole test-taking exercise really provide? Does this MOC process actually separate the good physician from the bad physician or the good test-taker from the bad one? Since ABIM never knows a doctor's scope of practice before their assessment, they make some heady assumptions about what they should test. In reality, the ABIM only tests what THEY think should be tested, rather than what matters to the particular physician's patient population. Worse still, since the ABIM remains completely unaccountable to doctors or patients in regard to their MOC process, their assessment may have absolutely no relevance to a particular physician's practice. Shouldn't we be discussing these issues before arguing how the test is constructed and scored?

No physician I know argues with the need for continuing, life-long education in medicine, especially when its performed in a relevant, transparent, informative, collegial and feedback-oriented process without a ulterior financial motive. If fact, most of us do this every week as part of our state licensure requirements and have plenty of continuing medical education credits to prove it. Allowing the ABIM to monopolize this process as we have through artificial MOC point acquisition exercises that are often irrelevant to a physician's scope of practice not only circumvents more healthy and sustainable learning environment, but also might cause more harm than good if that physician loses their practice privileges as a result.

In summary, I believe the ABIM's lucrative MOC process is no more valid than what doctors have already been doing for years before the American Board of Medical Specialties decided to make their MOC program an annual exercise. The MOC process remains unproven in its ability to improve patient care and (as we've now confirmed) discriminates against more senior physicians. Those of us who have endured this process multiple times have witnessed the growth of "board certification" from a self-imposed professional milestone to a money-making scheme filled with clinically-irrelevant busywork that often detracts, rather than augments, patient care (especially those non-validated "practice improvement modules").

It is time that doctors of all ages insist that these self-appointed non-profits organizations cease their attempt to become expensive continuing education providers and stick to what they do best: assessing a doctor's ability to reach a level of exceptionalism of their practice during their career, rather than pretending that they can assure some arbitrary level of ongoing practice adequacy for the business community. Until the ABIM comes to grips with their increasingly bipolar agenda, their ability to remain credible and relevant to practicing physicians, the public, and the mysterious "stake holders" they claim to serve will continue to be challenged, both on social media and in the court of law, as "significant consequences from losing certification" occur with increasing frequency to experienced and fully-capable physicians.

-Wes

Thursday, September 11, 2014

The Big Flail

After you've written on a blog for a long time, you begin to ask yourself why. Oh sure, there are the great opportunities for a single person to make a point, to act as a tiny tugboat trying to push a corporate mothership in a slightly different direction, but you begin to realize that there are very few times that actually happens. You try to provide a voice to issues that are often unheard, then realize that voice is only occasionally appreciated but more often duly noted, then ignored. This is the nature of internet and quite frankly, medicine now - it is a world of competing interests. On one side you have the patients, doing a messy job of getting sick, and corporate health care systems - either government, private, for-profit or non-profit - doing their very best to make sure their illness is neat and tidy, easy to control, perfectly understood, and quantifiable. To this end, each has their own agendas that must be served, be it another regulation, value-added improvement, or a profit motive to secure the bottom line.

This idea came to me yesterday in clinic. Increasingly, every microsecond of my day, my week, my weekend has now been efficiently parsed into tiny computerized scheduling chunks. It doesn't matter where I work, because like The Cloud, location doesn't matter - schedulers and administrative handlers can reach me, be it by beeper, computer, Outlook email, EPIC email, desk phone or my personal iPhone. There are so many places to check for messages that when I don't respond, the person trying to reach me just moves up the chain of communication options. Eventually there's no down time, no time to think, there are few places to go where there is quiet any longer. It's become life by a thousand interruptions - a Big Flail.

Increasingly, there's a push to do away with beepers and move telecommunications in medicine to my personal iPhone. But I an resisting this because I need to set a boundary between work and my personal life - if for nothing else but self preservation. We are told this is being done in the name of "security" and "non-secure beeper messages" but I think it's because people don't want to wait. They need their answer now. I really wonder what the evidenced based data on beeper message hacking is in health care and if more patients were helped or hurt by beeper data breeches. There's a better idea, they say: consolidate. It's more "efficient." I know, I'm such a Luddite. But to whom do I respond when that head administrator calls on my iPhone as I'm examining a patient? How to I separate a Twitter message from an ER message? Does the act of looking at my phone when I'm with a patient engender trust or an appearance of distraction?

It's hard to argue with "security" when someone creates a new medical policy. We all want to be secure. We all want to know that our most private and personal medical information is protected from prying eyes. But quite frankly (and this is very politically incorrect to say) real information security in medicine is a joke. After all, people's lives are perfectly encoded on a computer now and eight different billers, coders, insurance company trolls or hospital marketers can delve into that database of information and find specifics about a patient or group of patients with simply the click of a button. Phishing schemes make a mockery of our passwords. Seriously, who are we fooling? Let's be honest: paper charts housed in a known location behind a locked door were MUCH more secure.

Hurry up. Click here, click there, "Excuse me," "Can I have a moment of your time?", "There's a the 7 am meeting tomorrow," "What was that Ms. Jones?", "Yes, I'll try to make it," "Did you try it unipolar?", "Yes, I'll check my inbasket,""You left your addendum open,""They're calling for the cardioversion,""Should we add him in?", "I have to take my board review course, can you take call?,"The ER's calling,""Can you check her pacer, too, when you see her?", "Did you sign the EKG?"

Doctors need some quiet, down time, some time to think, to pay attention. We need to create our own boundaries between our personal and professional lives that are respected. We need to think we can get away, to regroup, have some quiet time for ourselves or with a patient, even for a moment. And if that means that some of us want to separate work from home by the use of a beeper instead of an iPhone, so be it.

Otherwise, our personal lives will become a Big Flail, too.

-Wes

This idea came to me yesterday in clinic. Increasingly, every microsecond of my day, my week, my weekend has now been efficiently parsed into tiny computerized scheduling chunks. It doesn't matter where I work, because like The Cloud, location doesn't matter - schedulers and administrative handlers can reach me, be it by beeper, computer, Outlook email, EPIC email, desk phone or my personal iPhone. There are so many places to check for messages that when I don't respond, the person trying to reach me just moves up the chain of communication options. Eventually there's no down time, no time to think, there are few places to go where there is quiet any longer. It's become life by a thousand interruptions - a Big Flail.

Increasingly, there's a push to do away with beepers and move telecommunications in medicine to my personal iPhone. But I an resisting this because I need to set a boundary between work and my personal life - if for nothing else but self preservation. We are told this is being done in the name of "security" and "non-secure beeper messages" but I think it's because people don't want to wait. They need their answer now. I really wonder what the evidenced based data on beeper message hacking is in health care and if more patients were helped or hurt by beeper data breeches. There's a better idea, they say: consolidate. It's more "efficient." I know, I'm such a Luddite. But to whom do I respond when that head administrator calls on my iPhone as I'm examining a patient? How to I separate a Twitter message from an ER message? Does the act of looking at my phone when I'm with a patient engender trust or an appearance of distraction?

It's hard to argue with "security" when someone creates a new medical policy. We all want to be secure. We all want to know that our most private and personal medical information is protected from prying eyes. But quite frankly (and this is very politically incorrect to say) real information security in medicine is a joke. After all, people's lives are perfectly encoded on a computer now and eight different billers, coders, insurance company trolls or hospital marketers can delve into that database of information and find specifics about a patient or group of patients with simply the click of a button. Phishing schemes make a mockery of our passwords. Seriously, who are we fooling? Let's be honest: paper charts housed in a known location behind a locked door were MUCH more secure.

Hurry up. Click here, click there, "Excuse me," "Can I have a moment of your time?", "There's a the 7 am meeting tomorrow," "What was that Ms. Jones?", "Yes, I'll try to make it," "Did you try it unipolar?", "Yes, I'll check my inbasket,""You left your addendum open,""They're calling for the cardioversion,""Should we add him in?", "I have to take my board review course, can you take call?,"The ER's calling,""Can you check her pacer, too, when you see her?", "Did you sign the EKG?"

Doctors need some quiet, down time, some time to think, to pay attention. We need to create our own boundaries between our personal and professional lives that are respected. We need to think we can get away, to regroup, have some quiet time for ourselves or with a patient, even for a moment. And if that means that some of us want to separate work from home by the use of a beeper instead of an iPhone, so be it.

Otherwise, our personal lives will become a Big Flail, too.

-Wes

Monday, September 08, 2014

Another MacGyver Moment in Pacemaker Implantation

Installing a permanent pacemaker or defibrillator has become commonplace event in cardiology these days. These devices implanted in a patient are comprised of two main parts: the lead(s) and the pulse generator. After installing the leads in the heart and connecting them to the pulse generator, the lead and pulse generator assembly are then placed beneath the skin in a small subcutaneous (or in rarer cases, submuscular) "pocket" that is created surgically. Considerable care is taken to cauterize bleeding vessels when the pocket is created. To facilitate visualization of these occasional bleeding vessels deep within the created pocket, I prefer to use a surgical headlamp to direct the light deep within the pocket cavity rather than relying on a conventional overhead surgical light. I have found that headlamps have helped me limit my incidence of post-operative pocket hematoma development.

So as things have had it, I seem to have a knack for attracting every eighty- or ninety-plus year old who needs an emergency pacemaker on the weekend when I'm on call, and this past weekend was no exception.

So the team was assembled and the pacemaker implantation equipment readied. They knew I liked a headlamp, so they dug deep into the recesses of their inventory to pull out their only headlamp that appeared to be from a bygone surgical era. Being pressed for time, I couldn't argue and had to make due, but knew that this headlamp might not be very reliable, especially as I saw how the headlamp's fiberoptic cord was secured to the light source that generated about as much light as a few well-lit candles by a cumbersome spring-loaded Rube Goldberg contraption. As I placed the headlamp on my head, and tightened the plastic strap that housed the headlamp to my head, I needed a backup plan in case the light failed.

Would I have to use the overhead light and make do, or might there be another way?

I needed another MacGyver Moment.

That's when my on-call staff team came up with a brilliant, simplified idea:

-Wes

(PS: This device is experimental and has not been approved by the FDA. Use this device at your own risk. If you experience headaches, nausea, difficulty with concentration, or an erection lasting for longer than four hours, discontinue use of this device and contact your doctor immediately. I have no commercial interest in this device. Also, since the headlamp still worked this weekend, no workaround was needed for the patient, but something tells me we might be getting a new headlamp soon.)

So as things have had it, I seem to have a knack for attracting every eighty- or ninety-plus year old who needs an emergency pacemaker on the weekend when I'm on call, and this past weekend was no exception.

So the team was assembled and the pacemaker implantation equipment readied. They knew I liked a headlamp, so they dug deep into the recesses of their inventory to pull out their only headlamp that appeared to be from a bygone surgical era. Being pressed for time, I couldn't argue and had to make due, but knew that this headlamp might not be very reliable, especially as I saw how the headlamp's fiberoptic cord was secured to the light source that generated about as much light as a few well-lit candles by a cumbersome spring-loaded Rube Goldberg contraption. As I placed the headlamp on my head, and tightened the plastic strap that housed the headlamp to my head, I needed a backup plan in case the light failed.

Would I have to use the overhead light and make do, or might there be another way?

I needed another MacGyver Moment.

That's when my on-call staff team came up with a brilliant, simplified idea:

|

| iPhone to the rescue! |

-Wes

(PS: This device is experimental and has not been approved by the FDA. Use this device at your own risk. If you experience headaches, nausea, difficulty with concentration, or an erection lasting for longer than four hours, discontinue use of this device and contact your doctor immediately. I have no commercial interest in this device. Also, since the headlamp still worked this weekend, no workaround was needed for the patient, but something tells me we might be getting a new headlamp soon.)

Friday, September 05, 2014

Cybernetic Medicine

Cybernetics, the scientific study of control and communication in the animal and the machine, used to be the stuff of science fiction. Today, thanks to a Faustian bargain between corporations, regulators, and politicians, it is defining medicine.

Every day, the exponential explosion of data entry and regulatory requirements doctors endure boggles the mind, all in the name of "health care."

Feedback is critical to field of cybernetics. And when Medicare's straps have you by the balls, you comply.

No longer is it good enough to learn a diagnosis or procedure code, doctors must attend online courses to learn how to use a new "calculator" to determine a more proper code. After all, there will soon be over 70,000 of them. Each more specific than the other, each more ridiculous. There are five data-entry fields to click on that calculator, each another tiny, yet time-consuming decision to be made, just to determine a code. No doubt teams of clever twenty-something computer programmers are overjoyed with their coding calculator and the way it pops up automatically on our screen when needed, then disappears. So pretty. So cool. See how easy they've made it to complete that regulatory requirement?

And this does not begin to address the increasingly algorithmically-driven electronic medical record and procedures envisioned in the years ahead. As if all things can and must be perfectly defined and quantified in medicine. No mistakes. No judgment needed. No need to type. Just close your eyes, click a few buttons, and follow the pathway. Stop thinking. Just do it. Enter the data. Resistance is futile.

After all, it's about the money...

... and perfect physician cyborgs.

Feel that strap tightening?

-Wes

Every day, the exponential explosion of data entry and regulatory requirements doctors endure boggles the mind, all in the name of "health care."

Feedback is critical to field of cybernetics. And when Medicare's straps have you by the balls, you comply.

No longer is it good enough to learn a diagnosis or procedure code, doctors must attend online courses to learn how to use a new "calculator" to determine a more proper code. After all, there will soon be over 70,000 of them. Each more specific than the other, each more ridiculous. There are five data-entry fields to click on that calculator, each another tiny, yet time-consuming decision to be made, just to determine a code. No doubt teams of clever twenty-something computer programmers are overjoyed with their coding calculator and the way it pops up automatically on our screen when needed, then disappears. So pretty. So cool. See how easy they've made it to complete that regulatory requirement?

And this does not begin to address the increasingly algorithmically-driven electronic medical record and procedures envisioned in the years ahead. As if all things can and must be perfectly defined and quantified in medicine. No mistakes. No judgment needed. No need to type. Just close your eyes, click a few buttons, and follow the pathway. Stop thinking. Just do it. Enter the data. Resistance is futile.

After all, it's about the money...

... and perfect physician cyborgs.

Feel that strap tightening?

-Wes

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)