But if you want to limit costs in medicine, it seems the government is intent on looking the other way:

At stake in the Harkonen case is a much broader debate over the standard for drawing clinical conclusions from scientific data. FDA typically requires two forward-looking or prospective trials, in which patients are randomly picked to get either an experimental drug or a placebo. That might be an appropriate standard for FDA approval, but it's an excessive burden for private firms that merely want to share their truthful research conclusions with doctors. The restrictions may also violate the First Amendment; Dr. Harkonen is appealing on those grounds to the Ninth Circuit.And it doesn't stop there.

At the same time government is limiting what private companies can legally communicate about their drugs, it has set a much lower standard for federal health agencies. President Obama has created new institutions with the sole mandate of running trials based on softer statistical standards. Retrospective studies will be the core occupation of a new "comparative effectiveness" research agency that has $4.1 billion to conduct government studies on medical products. The results will be used to inform federal treatment guidelines, as well as Medicare's payment policies.

At least $100 million of that $4.1 billion is being spent on promoting research results. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recently paid $26 million to the PR firm Ogilvy to "market and promote the adoption" of the findings.

Our clinical treatment "guidelines," now number some 2,766 for physical and psychiatric treatments according to the government's "Guideline Clearing House" (even, ironically, one for "Wandering"). These prescripts for care use a cornucopia of non-scientific methods, including opinions and case studies to formulate their recommendations, stating:

"Research findings and other evidence, such as guidelines and standards from professional organizations, case reports, and expert opinion were critiqued, analyzed, and used as supporting evidence."So when scientific rigor is given only lip-service by our government regulators, what will happen to the quality of care provided to our patients?

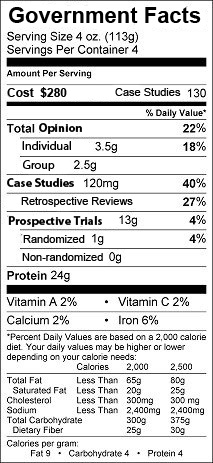

Maybe government recommendations should come with a food-label like disclaimer:

-Wes

2 comments:

Wes,

You may be talking apples and oranges here.

What the drug companies are restricted to marketing is what is clearly proven by studies to be the benefit of the drug and what it is FDA approved for. They need to reach FDA criteria of adequate study to promote their product for indications other than the FDA approved reason for use.

Clinical guidelines depend on the current level of understanding, which may or may not be adequately proven, but nevertheless, we need some guidelines till the pertinent questions are answered.

Good examples would be PSA testing in men, where there is no proven benefit that early testing results in increased longevity or decreased morbidity, but we need some consensus on how to use the test till studies are completed looking at these questions. The alternative would be to pull the test from the market till this research is completed, but since there are many clinical reasons for doing the test other than diagnosis of prostate cancer, this would not be possible.

Another example is statins in patients with no proven cardiovascular disease. Do we know for certain at this stage that early treatment with statins is beneficial in this asymptomatic population? I don't think we clearly know the answer, but the NCEP group laid down guidelines for treatment guidelines till we more clearly know the answer.

So the science need not to be as rigorous as one might entertain for a medication being marketed by a pharmaceutical producer. Double standard? I don't think so. I would be more worried about letting loose pharma reps to tout the beneficial effects of their product for every indication on us unsuspecting primary care docs.

When I see a patient with a left cheek mass, I don't use a "consensus" to decide what to do. I use judgment, based on my training and experience to choose to do an FNA on this mass before moving on to more expensive, invasive, and costly methods. If a new way comes along to investigate this problem, I likely have enough judgment to make an initial decision about whether it is helpful enough to add it to my armamentarium. Waiting on consensus denies our ability to use judgment. That doesn't mean we don't take into account what others say, it just means that we understand that what others say may be right or wrong. Our judgment helps us decide. How many patients will suffer if the NCEP (whatever that is!) is incorrect? I contend that the science should be just as rigorous if we are going to be asked to treat patients by those guidelines. Best Practices are not always right and not aways applicable at every level of care (paraphrase from Jerry Groopman, Harvard). I refuse to be forced to practice bad medicine whether it be by insurance companies, the government, or misguided doctors! Show me the data with good statistical analysis (sadly, this is frequently absent) and I will consider if this works for my patients. Save me and my patients from the "panel of experts!"

Post a Comment