"Welcome," I thought, "to the Health Care Industrial Complex." This meeting was, after all, designed for me and the other Heart Rhythm Specialists from all over the world.

| HRS Infinity Circle Supporters |

Of course they were.

Twenty-six years ago I entered the North American Society and Pacing and Electrophysiology (NASPE) as a young fellow in cardiac electrophysiology competing for the Young Investigator Competition. I was nervous as hell as I practice and re-practiced by presentation. I was competing against some of the best and brightest and was thrilled at the opportunity, the heady notoriety, and the opportunity to rub noses with the reviewers (international senior mentors) first hand. Back then I did not have the perspective I have now with the interplay of forces that have come to define US health care. I had no concept of the powerful influence that the vast sums of money, lobbies, special interests, regulators, and oversight agencies have in medicine.

Since that time, NASPE has changed its name to the Heart Rhythm Society to reflect a more global mission. Over the years I have seen the bureaucratic and political influence change the landscape of medicine as I never imagined as I struggle to cope with what it means to practice medicine today. I suppose when one considers that for many communities in America, health care is their economy, I shouldn't be surprised that the business and politics of medicine are now more important than ever.

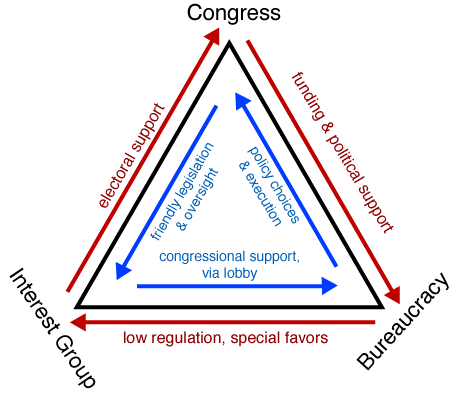

Years ago near the start of the Vietnam War, President Dwight D. Eisenhower coined the phrase "military industrial complex" in his farewell speech to America. He was describing the policy and monetary relationships that exist between legislators, our national armed forces, and the military industrial base that supports them. These relationships include political contributions, political approval for military spending, lobbying to support bureaucracies and oversight of the industry. The concept began with the concept of coordination between the government and the private sector to provide weaponry to government-run forces.

Now we have the private sector providing funding for our instruments of health care. We see companies that supply medical devices, drugs, insurance, electronic medical records and companies that support lobbying efforts and data mining and richly-paid oversight entities. Today, however, the budget is much, much larger for medicine than the military. Our "health care industrial complex" has grown into the monster it is today with a supporting flotilla of corporate, special interest, regulators and oversight entities, with doctors and patient's swept up by its wake.

Some have called this the "Iron Triangle." And just like it's original reference for the military, we should recognize that it pertains to health care, too. While this may be distasteful to many (including myself), I have also come to recognize that like the military, we need health care. Unfortunately for all of us, this monstrous bureaucratically-wasteful system is what we've created. For me, I find it helpful to understand this interplay, because it helps me focus on my role as a doctor today.

|

| The Iron Triangle |

I can only hope that our younger medical students, residents, fellows, and younger doctors get taught this perspective. Much too often I see them looking more like lambs being led to slaughter. Hopefully, a little insight will help them cope with the seemingly endless bureaucratic and oversight "ideas" that keep surfacing as we struggle to care for our patients. Hopefully this perspective will keep them engaged in pushing back when the onerous becomes intolerable. Hopefully they'll come to understand what they're up against before they throw up their hands in disgust.

Perhaps bringing these concepts to consciousness will allow us to become coordinated advocates for our patients who are being affected by these very same forces. Maybe then, we can continue to hold true to what we love about medicine, and beat back the Iron Triangle that is making it so difficult to do so.

-Wes

5 comments:

Your industry is not alone. Think education. Think law enforcement. And,as you noted, it is the military. It is the privatization of America.

I think, actually, that it is more the cronyization of America than simply privatization.

In any case, it's a very corrosive situation.

If the government lacked the power to affect private entities, then private entities would have no incentive to spend money on lobbying the government.

It's not too difficult to identify problems. Identifying alternatives that truly improve things, now that's a different matter.

Anony 11:12 am:

As any good engineer knows, to solve a problem, you must first identify and define its scope. Only then can solutions to improve the problem be developed with time. Until we teach our best and brightest new physicians a better understanding of the problems they will face in the years ahead, you and I won't stand a chance of a doctor putting our interests before the system's.

Post a Comment