I just returned from the American College of Cardiology and wanted to write down a few of my 50,000-foot impressions from the meeting for, as the song goes, the times, they are a-changin'.

First, while I don't know the overall attendance at the meeting, there really appeared to be fewer attendees. Interestingly, the outside-the-US contingent seemed strong, but by comparison, the US presence at the meeting seemed much lighter (no facts to support this, just my impression).

The pharmaceutical and medical device displays seemed awkwardly overdone. Gigantic displays, lots of sales people standing around, with really not much to do. The amount of money these companies spend to attract doctors in an era when doctors really aren't the purchasers of this stuff anymore, seems crazy - like they haven't gotten the memo. And for goodness sakes, pharma needs to understand how bad it looks when they're charging $6 a pill to our patients on novel oral anticoagulants and they've got these bulls**t displays. Either tone it down, or cut your price… er, never mind: do both.

Surprisingly, I never saw a single model walking on a regular treadmill - a standard at every cardiology meeting I have ever attended. What this means, I'm not sure. Perhaps the ACC has matured to realize that women cardiologists are a growing force, or (more likely) the advertisers understand that no one cared about regular treadmills (they don't make any revenue) and are sick and tired of standing in from of them at work.

RFID tracking seemed larger than ever. Little scanner doomajiggies were all over the place to track us wherever we went, that is, of course if we agreed to have one in our badge. (I was happy to see that the ACC respected by wishes not to have the RFID in my badge, and none was there). One thing that several doctors noticed (and I confirmed): they really didn't care if you had your badge on UNTIL you went to the expo floor, showing what really matters, I guess.

I had the great pleasure of meeting and chatting with a few fellows from across the country and around the world: New York, Massachusetts, North Carolina, California, China, China, and China. These younger folks were cool, but clearly lamenting that it might not be one they participate in much longer. For the most part, most of them were there on much of their own nickel. I quickly polled them to inquire about the annual stipend they receive from their institutions for these things, and the numbers I heard were quite low: from $1500 to $2500. Between cuts to doctors' income and low expense stipends, it is no wonder more and more physicians are staying away - kind of sad for doctors, sure, but really sad for these bright, eager residents and fellows. One is starting to wonder how many more years such expensive sessions will continue.

The other big thing that I noticed at this meeting: not much was scientifically new. It was striking. Think about it: the big trials were a trial on TAVR, a few talks on Mitra-clip, renal denervation, cardiac resynchronization, and pericarditis. Maybe the PCSK9 inhibitors that drop LDL substantially in folks with familial hypercholesterolemia were novel, but that one's not really my bag… It just seems that the of innovation in US medicine has taken a pause. Even in the posters: meta-analyses of old big trials seemed to outnumber and new big trials. It's different now. The cuts are real.

Finally, there was an important first at the meeting. I was impressed that the topic of social media in medicine was given it's own real, live session with it's own central room at #ACC14. I was even more amazed they invited me. After all, I haven't exactly ingratiated myself with the College lately. To their credit, however, they are giving folks like you and me a place to learn about and a platform to promote what I believe to be an important tool for physicians in the years ahead. For that, I am truly grateful. We are, after all, are all professionals all doing this crazy work of medicine together. We may not agree at times, but I think we all want to improve the system for our patients' sake, and social media is a very powerful way to affect change, act collectively, vet ideas, and improve our health care system for the better. Industry, too, is learning from doctors and patients as they use social media to critique, explain, and promote ideas and tools for better patient care. Sure there will be bumps. Sure there will be disagreements. And change may not come right away. But more more often than not, with enough collective voices reaching some compromise, there will be effective change for the better. Seriously, where else can we get value like that?

So to the ACC leadership and all the great people I had the chance to meet, discuss, learn from, share ideas with, thank you. It was a blast.

-Wes

Monday, March 31, 2014

Sunday, March 30, 2014

Is Maintenance of Certification Our Next Tuskegee?

“An experiment is ethical or not at its inception, it does not become ethical post hoc – ends do not justify means. There is no ethical distinction between ends and means.”

-- Henry K. Beecher, MD

New Engl J Med 274(24) June 16, 1966 pp 1354-1360.

“For the most part, doctors and civil servants simply did their jobs. Some merely followed orders, others worked for the glory of science."

-- John Heller, Director of the Public Health Service's Division of Venereal Diseases

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment was an infamous clinical study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Service to study the natural progression of untreated syphilis in rural African American men who thought they were receiving free health care from the U.S. government. The Public Health Service started working with the Tuskegee Institute in 1932. Investigators enrolled in the study a total of 600 impoverished sharecroppers from Macon County Alabama. Three-hundred ninety-nine (399) of those men had previously contracted syphilis before the study began, and 201 did not have the disease. The men were given free medical care, meals, and free burial insurance, for participating in the study. They were never told they had syphilis, nor were they ever treated for it. According to the Centers for Disease Control, the men were told they were being treated for "bad blood", a local term for various illnesses that include syphilis, anemia, and fatigue.

The 40-year study was controversial for reasons related ethical standards, primarily because researchers knowingly failed to treat patients appropriately after the 1940s validation of penicillin as an effective cure for the disease they were studying. Revelation of study failures by a whistleblower led to major changes in U.S. law and regulation on the protection of participants in clinical studies. Now studies require informed consent, communication of diagnosis, and accurate reporting of test results.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study led to the 1979 Belmont Report and the establishment of the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). Importantly, it also led to federal laws and regulations requiring Institutional Review Boards for the protection of human subjects in studies involving human subjects.

Fast forward thirty-five years.

Could the new American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) mandate for participating in their Maintenance of Certification (MOC) process unilaterally imposed 1 January 2014 so they can maintain a publicly-reported maintenance of certification "status" be violating ethical standards set forth by the 1979 Belmont Report?

Let me explain why I think it does.

The increasingly complicated test- and survey-taking exercise called "Maintenance of Certification" has never been scientifically proven to improve physician quality. Our society's inability to agree on a definition of a "quality" physician (and how to measure those qualities) is part of the reason why this issue has never been studied. For instance, should we define a "quality" physician on the basis of his or her empathy, surgical skill, lack of complications, ability to recall facts or some combination of these or other attributes? The reality is, it is nearly impossible to adequately define a "quality" physician at the outset.

But the issue of maintaining "quality" health care delivery is critical to those paying for health care services (CMS and insurers, aka, "stakeholders"), especially now in this era of health care reform. Payers want to assure they receive the most value for their dollars spent in health care. Patients want to be reassured that they are receiving competent care by a physician, especially in a time where cost-cutting, deployment of unproven electronic medical systems, use of non-physician care-givers, and shortened physician training and work hours has occurred. Seeing an opportunity, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the ABIM stepped in to help the government define physician quality. Through the assurances of their leadership, the ABIM led "stakeholders" to believe that (1) quality is easy to measure (after all, they have a thorough testing "process") and (2) the responsibility for determining physician quality should rest with individual physicians. This leap of faith by government officials is similar to the Tuskegee era when government physicians were similarly obsessed with African American sexuality, believing that the responsibility for the acquisition of syphilis rested solely upon the individual.

Because the Maintenance of Certification process imposed by the American Board of Internal Medicine is unproven, it is, at best, an experiment that attempts to assure physician quality on patients without a defined hypothesis (what, really, does the ABIM test with the MOC process?) or informed consent. The issue of informed consent is critical, in my view, because the psychological, financial, and social consequences of NOT passing the test to doctors and their patients have never been evaluated.

|

| The "MOC Complex" at ACC2014 (click to enlarge) |

First, I learned that the pass rate this year (2013) for internal medicine specialists was 86%, and for cardiac electrophysiologists was 84%. This means that fourteen percent of internists and sixteen percent of cardiac elecrophysiologists did not pass their test. (We were assured that 97% "ultimately" pass, however, but no data were supplied to the audience to this effect).

The second thing I learned directly from Dr. Baron yesterday during the question and answer period was this: the ABIM has never studied the psychological, social, or financial impact that NOT passing the MOC process upon physician test-takers. This is not a small issue, especially if one considers that many hospitals are beginning to tie the ongoing Maintenance of Certification process to the issuance of hospital privileges to practice medicine. How could anyone trained in the ethics of scientific study and research permit such an egregious oversight to the protection of physicians?

From the 1979 Belmont Report:

The expression "basic ethical principles" refers to those general judgments that serve as a basic justification for the many particular ethical prescriptions and evaluations of human actions. Three basic principles, among those generally accepted in our cultural tradition, are particularly relevant to the ethics of research involving human subjects: the principles of respect of persons, beneficence and justice.Let's examine each of these principles described in the Belmont Report in regards to MOC testing.

Regarding respect for persons:

Respect for persons incorporates at least two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection.Today, physicians are "persons with diminished authority" in the certification and licensure discussion. The decision to invoke every-two-year testing was imposed by leadership of several physician organizations whose leadership have had strong ties to government agencies (including the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, a la Dr. Baron) without the approval of their membership. Further, the MOC process is already being used by some hospitals as a lever to dispense hospital privileges without proof that the MOC process assures physician quality, however might have been defined.

Regarding beneficence:

Persons are treated in an ethical manner not only by respecting their decisions and protecting them from harm, but also by making efforts to secure their well-being. Such treatment falls under the principle of beneficence. The term "beneficence" is often understood to cover acts of kindness or charity that go beyond strict obligation. In this document, beneficence is understood in a stronger sense, as an obligation. Two general rules have been formulated as complementary expressions of beneficent actions in this sense: (1) do not harm and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms.Given the fact that the negative consequences of failing to re-certify in medicine are very real for doctors, failing to pass the ABIM's tests may, in fact, harm them. No attempt to minimize harm to physicians has occurred. No attempt has been made to warn physicians about the negative consequences of what might happen to them if they fail to maintain their certification in good "status." Worse still: not allowing physicians to practice medicine may actually harm, rather than benefit, the doctor's patients! The ABMS and ABIM have clearly turned a blind eye to this possibility.

Finally, in regards to the last critical element of the Belmont Report, justice:

Who ought to receive the benefits of research and bear its burdens? This is a question of justice, in the sense of "fairness in distribution" or "what is deserved." An injustice occurs when some benefit to which a person is entitled is denied without good reason or when some burden is imposed unduly. Another way of conceiving the principle of justice is that equals ought to be treated equally. However, this statement requires explication. Who is equal and who is unequal? What considerations justify departure from equal distribution? Almost all commentators allow that distinctions based on experience, age, deprivation, competence, merit and position do sometimes constitute criteria justifying differential treatment for certain purposes. It is necessary, then, to explain in what respects people should be treated equally. There are several widely accepted formulations of just ways to distribute burdens and benefits. Each formulation mentions some relevant property on the basis of which burdens and benefits should be distributed. These formulations are (1) to each person an equal share, (2) to each person according to individual need, (3) to each person according to individual effort, (4) to each person according to societal contribution, and (5) to each person according to merit.So who is served by the Maintenance of Certification process, really? Are patients? Doctors? Or the leadership of ABIM?

Questions of justice have long been associated with social practices such as punishment, taxation and political representation. Until recently these questions have not generally been associated with scientific research. However, they are foreshadowed even in the earliest reflections on the ethics of research involving human subjects. For example, during the 19th and early 20th centuries the burdens of serving as research subjects fell largely upon poor ward patients, while the benefits of improved medical care flowed primarily to private patients. Subsequently, the exploitation of unwilling prisoners as research subjects in Nazi concentration camps was condemned as a particularly flagrant injustice. In this country, in the 1940's, the Tuskegee syphilis study used disadvantaged, rural black men to study the untreated course of a disease that is by no means confined to that population. These subjects were deprived of demonstrably effective treatment in order not to interrupt the project, long after such treatment became generally available.

There are significant financial incentives driving the marketing of the ABIM's ongoing MOC process to America's physicians. From the ABIM's own 2012 Form 990 that I could retrieve, the ABIM earned $30,661,314 from their members for examination fees, $17,509,141 for Maintenance of Certification, and an additional $970,415 for exam development, supplying duplicate certificates, and re-scores of the examination. Of the total revenues reported by the ABIM in 2011 ($49,304,645) fully 48.6% ($23,937,881) went to staff salaries, other compensation, and employee benefits. Christine Cassels, MD alone (who served as President and CEO at the time), earned $786,751 that year and had her spouse's travel fees to meetings thrown in, too. It goes without saying that the leadership of these organizations have received salaries far higher than most of their physician members. Justice (as defined by the Belmont Report) can hardly be served when scales are tipped so heavily toward those of our own profession that stand to benefit so handsomely from this certification process.

It is time that doctors and patients understand exactly what has transpired with the foisting of the ongoing MOC process upon America's physicians. Just as the Tuskegee experiments in Macon County Alabama did years ago, well-meaning members of our profession have represented physician "quality" by their own standards that include the ability to perform a serious of test- and survey-taking exercises without responsibly admitting the harms this process might have on their colleagues and their patients. Like the serious breaches of ethical standards that occurred when doctors worked "for the glory of science" in the Tuskegee era, this unfortunate unproven experiment of MOC re-certification by the ABIM continues unabated without checks and balances.

It is time for this injustice against physicians to stop. Responsible physicians and their patients everywhere need to rise up and demand accountability by the ABIM for their ethical breaches that have occurred. The heavy marketing of the benefit of this process without acknowledging its potential harms is dangerous to both doctors and patients. Further, it is not okay to entrap physicians by making them pay for an unproven process that could destroy their social status and ability to earn a living.

To believe otherwise is about as unethical as it gets.

-Wes

P.S.: Here's a link to an anti-MOC petition underway.

Friday, March 28, 2014

Social Media at Scientific Sessions

More and more physicians are entering the social media space - so much so that even our more classic academic physician colleagues are joining in. But there can be challenges that arise at scientific sessions when the old way of professional discourse meets the new way of social media.

Robert A Harrington, MD (Chair, Dept of Medicine, Stanford University, CA) and Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc (Northwestern Medical Center, IL) discuss these challenges nicely at theheart.org and offer some interesting insights and tips for doctors, both young and old, as they consider entering the social media space.

-Wes

P.S.: Then again, if you're still unsure how Twitter even works, consider this Twitter primer.

Why Do Most Medical Professional Societies Call Chicago Home?

Professional medical societies "concerned" about physician education, advocacy and quality appear to have multiplied at an alarming rate over the years. Interestingly, it seems many of the professional offices of these societies are based in Chicago. On my review, no other city in the United States hosts more of them (not even Philadelphia).

Why is this?

First, there is the grand-daddy of all physician professional societies: the American Medial Association based at AMA Plaza, 330 N Wacker Drive, Chicago.

Next, there's the American Board of Medial Specialties (ABMS) (who boasts its supervisory role over 24 subsidiary specialty medical societies across the nation, including the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American College of Cardiology among others) that has it's home at 222 North LaSalle Street in Chicago, just blocks away from the AMA building.

Next, there's the little-known Council on Medical Specialty Societies, who also seemed to be concerned with physician "quality" located just across the Chicago river at 35 E. Wacker Drive.

And let's not forget the Acceditation Council on Graduate Medical Education who oversees all graduate medical education in the United States located at 515 North State Street in Chicago.

Makes you wonder why all of these societies are within blocks of each another in Chicago.

Maybe it's so they can have lunch together. Maybe it's because of all of the academic medical centers located here in Chicago who have retiring professors that need a place to land. Maybe it's because of the state's political leanings. Or perhaps it's just because of Chicago's fairly central US geographic location?

One thing's for sure, it certainly isn't because of low real estate prices or low taxes.

-Wes

Why is this?

First, there is the grand-daddy of all physician professional societies: the American Medial Association based at AMA Plaza, 330 N Wacker Drive, Chicago.

Next, there's the American Board of Medial Specialties (ABMS) (who boasts its supervisory role over 24 subsidiary specialty medical societies across the nation, including the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American College of Cardiology among others) that has it's home at 222 North LaSalle Street in Chicago, just blocks away from the AMA building.

Next, there's the little-known Council on Medical Specialty Societies, who also seemed to be concerned with physician "quality" located just across the Chicago river at 35 E. Wacker Drive.

And let's not forget the Acceditation Council on Graduate Medical Education who oversees all graduate medical education in the United States located at 515 North State Street in Chicago.

Makes you wonder why all of these societies are within blocks of each another in Chicago.

Maybe it's so they can have lunch together. Maybe it's because of all of the academic medical centers located here in Chicago who have retiring professors that need a place to land. Maybe it's because of the state's political leanings. Or perhaps it's just because of Chicago's fairly central US geographic location?

One thing's for sure, it certainly isn't because of low real estate prices or low taxes.

-Wes

Saturday, March 22, 2014

ACC's 2014: What's Out There That's New?

I will be attending the ACC 2014 Scientific Sessions this year in Washington, DC. Theheart.org has a nice post covering some of the early highlights of the conference (sorry, registration required).

But I'm going to try something a bit different this year. Call it self-indulgence. I'm going to try all my might to pull my head out of the corporate weeds for a while and look to my colleagues and start-up friends to see where the innovation in health care is going, not where we've been. After all, MADIT CRT, TAVR (Corevalve included), renal denervation (SYMPLICITY-3), colchicine in pericarditis (CORP 2 Trial), and 3-year results of bariatric surgery are, well, not exactly cutting edge.

I need to get back to my roots more. While I'm a doctor, I'm also a biomedical engineer, a social media nerd, and a guy who loves innovation and creativity in medicine. I want to discover new ideas, new people. I want to discover those who want to attack the colossal challenges patients will have in health care delivery in the years ahead with new and innovative strategies for cardiovascular disease or cardiac arrhythmia management. I want to connect with those who want to upend the status quo. I want to wander around in the swamp of creativity instead of being led lock-step toward more marketing spin.

Am I crazy? Does such a venue exist at this years' ACC Scientific Sessions?

We'll see.

-Wes

(If you'd like to connect or have something that's really cool that might be interesting to discuss over breakfast or lunch one day, shoot me an e-mail at wes - at - medtees dot com or message me via Twitter at @doctorwes . Please, no marketing pitches.)

But I'm going to try something a bit different this year. Call it self-indulgence. I'm going to try all my might to pull my head out of the corporate weeds for a while and look to my colleagues and start-up friends to see where the innovation in health care is going, not where we've been. After all, MADIT CRT, TAVR (Corevalve included), renal denervation (SYMPLICITY-3), colchicine in pericarditis (CORP 2 Trial), and 3-year results of bariatric surgery are, well, not exactly cutting edge.

I need to get back to my roots more. While I'm a doctor, I'm also a biomedical engineer, a social media nerd, and a guy who loves innovation and creativity in medicine. I want to discover new ideas, new people. I want to discover those who want to attack the colossal challenges patients will have in health care delivery in the years ahead with new and innovative strategies for cardiovascular disease or cardiac arrhythmia management. I want to connect with those who want to upend the status quo. I want to wander around in the swamp of creativity instead of being led lock-step toward more marketing spin.

Am I crazy? Does such a venue exist at this years' ACC Scientific Sessions?

We'll see.

-Wes

(If you'd like to connect or have something that's really cool that might be interesting to discuss over breakfast or lunch one day, shoot me an e-mail at wes - at - medtees dot com or message me via Twitter at @doctorwes . Please, no marketing pitches.)

Monday, March 17, 2014

Doctors as Drug Reps

There's a new gig for doctors - as drug rep:

No doubt these doctor drug reps will soon figure prominently as speakers at our upcoming scientific sessions.

God help us.

-Wes

Because they will be employees of Glaxo, the company won’t have to report payments to doctors under the so-called Sunshine Act in the U.S. that requires such disclosures. On the other hand, their credibility may be questioned, and they won’t be able to answer questions such as how they would treat a patient with specific symptoms or problems, given that they aren’t practicing physicians, Khedkar said.Ironically in the same article, a few paragraphs down:

In addition to targeted e-mails and Web seminars, drugmakers are increasingly using mobile platforms including instant replies to questions sent by text message that doctors can use while seeing patients, Khedkar said.Heh. There you have it: another regulatory problem solved.

No doubt these doctor drug reps will soon figure prominently as speakers at our upcoming scientific sessions.

God help us.

-Wes

Sunday, March 16, 2014

How Much Do Doctors Really Earn?

An interesting infographic was recently posted on Sermo (with references noted at the bottom):

I found this infographic interesting for several reasons.

The information puts the high US physician salary touted by the mainstream media and political policy makers in perspective with other countries when time spent providing care is considered.

However, the data presented in this infographic also address the important issue of training debt that currently averages about $300,000 for US physicians (We should note that the 2013 Association of American Medical Colleges report on medical student debt mentions only the "median" debt of medical students: $170,000 - a much more palatable way to spin the truth in favor of our educators.)

So while Congress grapples with the SGR "fix" that is never enforced anyway, there are much bigger issues to consider in regard to physician compensation going forward as the US struggles with its growing doctor shortage.

-Wes

| |

| (Click to enlarge) |

I found this infographic interesting for several reasons.

The information puts the high US physician salary touted by the mainstream media and political policy makers in perspective with other countries when time spent providing care is considered.

However, the data presented in this infographic also address the important issue of training debt that currently averages about $300,000 for US physicians (We should note that the 2013 Association of American Medical Colleges report on medical student debt mentions only the "median" debt of medical students: $170,000 - a much more palatable way to spin the truth in favor of our educators.)

So while Congress grapples with the SGR "fix" that is never enforced anyway, there are much bigger issues to consider in regard to physician compensation going forward as the US struggles with its growing doctor shortage.

-Wes

Friday, March 14, 2014

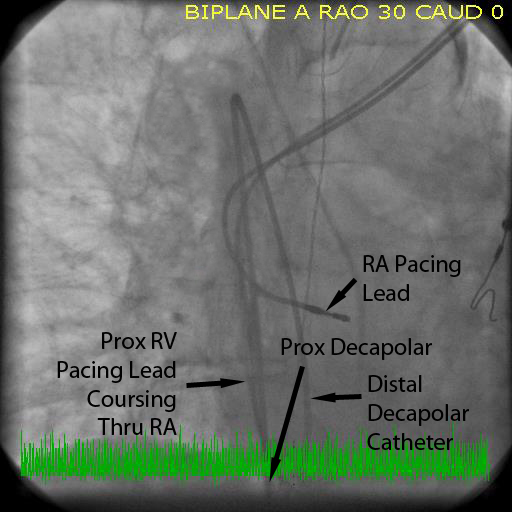

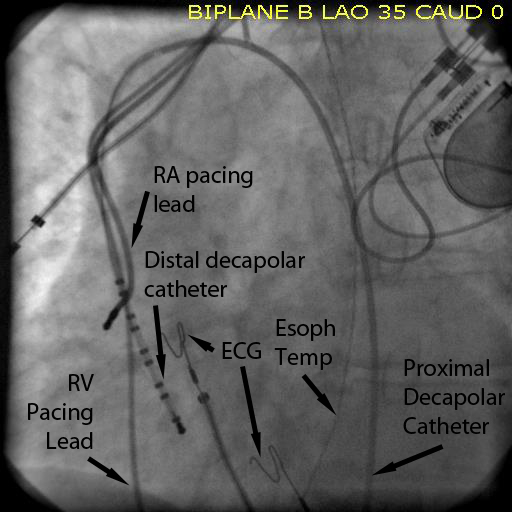

Case Study: An Unusual Catheter Course to the Right Atrium

Recently, our laboratory was performing a catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a patient with a permanent pacemaker previously implanted from the left axillary venous approach. The fellow placed a decapolar catheter from the left femoral vein, but it took an unusual course to the right atrium. Attempts to place the catheter via a more typical course could not be achieved.

Here are the RAO and LAO fluoroscopic images he saw (labeled for your convenience):

At first, the fellow thought the catheter was extravascular was the catheter passed behind the heart, but continued advancement resulted in the catheter entering the right atrium.

Here's the LAO Cineangiogram of the finding that helped us identify the cause:

Here's the RAO image of the same shot:

What is this? What happened next?

-Wes

PS: If you can't wait, here's a link to a pretty illustration of the anatomy. Note the hepatic drainage to the right atrium is separate from the drainage of the IVC in this anomaly. Here's another link to factoids from the radiology literature regarding this interesting finding.

Here are the RAO and LAO fluoroscopic images he saw (labeled for your convenience):

|

| RAO Fluoroscopic Image (click to enlarge) |

|

| LAO Fluoroscopic Image (click to enlarge) |

Here's the LAO Cineangiogram of the finding that helped us identify the cause:

Here's the RAO image of the same shot:

What is this? What happened next?

-Wes

PS: If you can't wait, here's a link to a pretty illustration of the anatomy. Note the hepatic drainage to the right atrium is separate from the drainage of the IVC in this anomaly. Here's another link to factoids from the radiology literature regarding this interesting finding.

Thursday, March 13, 2014

A Quiz: Is Maintenance of Certification Worth It?

Recently, I noted that the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) was going to offer an incentive payment of 0.5% beginning 1 January 2014 to doctors who participate in the American Board of Medical Specialties' proprietary Maintenance of Certification® (MOC) process and are in good standing.

I wondered: how much more money does that extra payment from CMS represent for the average physician?

So I decided to do some back-of-the-envelope calculations to see what the investment of hours of studying the ABMS's proprietary materials, test-taking, board review courses, patient survey-taking, and practice improvement studies could garner for the average physician. Is there some real dollar-and-cents value to participating in this process?

To estimate this value, I made some assumptions to simplify the math:

(1) Given the above assumptions, how much more income will the average US male physician earn as a result of their total PQRS payment from CMS each year?

(2) How much does this additional PQRS income represent per patient visit?

(3) In your estimate, is this additional income worth the time spent away from your patients or your family events because of study requirements?

Please show your work (and/or your thoughts) in the comments.

Rest assured you will not be timed on this test nor will you receive any renumeration, CME credit, or MOC credit for your participation in this fun. Rather, it is hoped it helps educate physicians on what they'll be getting for their "required" $194 to $256 fee paid annually to the ABIM.

The first one to answer this quiz correctly will be officially crowned with the invaluable and highly-esteemed Dr. Wes Adminstrative Oversight Award®. (I added the trademark symbol to this fictitious award because I'm sure this exercise will be of great value one day.)

Good luck!

-Wes

PS: In the interest of saving time for my busy colleagues who'd rather cut to the chase, here's a link to my back-of-the-envelope calculations. (Feel free to point out errors in the comments)

I wondered: how much more money does that extra payment from CMS represent for the average physician?

So I decided to do some back-of-the-envelope calculations to see what the investment of hours of studying the ABMS's proprietary materials, test-taking, board review courses, patient survey-taking, and practice improvement studies could garner for the average physician. Is there some real dollar-and-cents value to participating in this process?

To estimate this value, I made some assumptions to simplify the math:

- First, I assumed the Mediscape 2013 average male physician salary in America was reasonably accurate ($259,000/yr) and will not change this year.

- Doctor salary is taxed at a 24% rate after withholdings are considered.

- No time during regular work hours is devoted to performing any MOC requirement.

- The average US male physician works and average of 45 weeks per year, 5 days per week for their total salary.

- The doctors only see Medicare patients.

- Every patient office visit is billed as a 99213 (established patient visit - 15 min). (I know, not realistic, but simple to estimate)

- Doctors work 8AM-12 noon and 1pm-5pm daily, seeing 32 patients per day, every day they work.

- Income medicare pays the physician for each 99213 established patient visit is $69.66 and there is a 100% collection rate

(1) Given the above assumptions, how much more income will the average US male physician earn as a result of their total PQRS payment from CMS each year?

(2) How much does this additional PQRS income represent per patient visit?

(3) In your estimate, is this additional income worth the time spent away from your patients or your family events because of study requirements?

Please show your work (and/or your thoughts) in the comments.

Rest assured you will not be timed on this test nor will you receive any renumeration, CME credit, or MOC credit for your participation in this fun. Rather, it is hoped it helps educate physicians on what they'll be getting for their "required" $194 to $256 fee paid annually to the ABIM.

The first one to answer this quiz correctly will be officially crowned with the invaluable and highly-esteemed Dr. Wes Adminstrative Oversight Award®. (I added the trademark symbol to this fictitious award because I'm sure this exercise will be of great value one day.)

Good luck!

-Wes

PS: In the interest of saving time for my busy colleagues who'd rather cut to the chase, here's a link to my back-of-the-envelope calculations. (Feel free to point out errors in the comments)

Sunday, March 09, 2014

E-Flooded

I have been a way from blogging for a bit - tried to clear my head a bit with a vacation skiing - left the computer at home, disconnected (as best I could), and had the luxury of feeling the knees working less fluidly than they had before, but still had some fun for a brief 3-day stint. It was nice to notice that there's a whole world out there - beautiful mountains, fresh air, nice friends. All things considered, I am pretty lucky to have a stable job, appreciative patients, and a fulfilling career.

But it didn't take long after my return to work for me to feel flooded again. Two days after returning to work, it was like I never left. Perhaps it's like that for most busy folks, but somehow the world of health care delivery feels more frenetic than ever. The in-basket messages, the mountains of results, the re-scheduled patients on top of those already scheduled, the seemingly endless phone and e-mail messages, the late-night consults after a full day of procedures - all demanding time - it's bordering on crazy. I have several nurse practitioners who assist, but the volume of electronic patient care that's happening now is overwhelming to even the most computer-savvy of us doctors.

And all of this communication is not compensated. There are no "RVUs" for answering an e-mail. There are no "RVUs" for speaking on the phone. There are no "RVU's" for typing. No "RVUs" for data entry and clicking a mouse. Physician time means nothing to programmers and policy-makers.

It's a larger symptom, I think, of the new "efficiencies" built into the electronic medical record (EMR) that has become ubiquitous with the world of medicine today. Information flies so fast and there's so much of it that it's getting almost impossible for doctors to keep up with the screen responsibilities, not to mention their care responsibilities. The EMR is no longer just an EMR. The EMR has morphed into a scheduling agent, pharmacy, reminder pad, calculator, care pathway generator, instant-messaging service, a procedure orderer-by-proxy (and guideline) and a patient messaging portal that, aside from a 400-character limit, provides unprecedented access to physician in-boxes and schedules. There are so many buttons that they no longer fit on a single screen and the "allergy" field no longer can be displayed as it's pushed out of the way by the name of the patient's insurer. Add to this the constant and growing influx of patients (thanks to marketing pushes and programs to spur referrals), voluminous administrative meetings, and growing CME requirements, it's no wonder many of us feel flooded. I work later than ever now thanks to these electronic "efficiencies," then find myself waking in the middle of the night wondering: Did I call Ms. Smith? Did I miss something? Did I put that order in? When am I going to do those result notes?

I think I'm suffering from post-traumatic electronic overload disorder (PTEOD).

Oh sure, we could hire another guy or gal to offload some of the work - maybe even hire a wasteful manpower-intensive scribe like those that work in some ERs that click for cash - but that really won't help stem the ongoing barrage of information that is now pummeling physicians and their care teams at an unprecedented rate. Sadly, I don't see this trend changing anytime soon - the business case for the EMR is just too attractive for hospitals and payers. Still, with the prospect of ICD-10 and it's 71,924 procedure codes and 69,823 diagnosis codes (that must be paired correctly lest doctors not be paid) just around the corner, I fear that physician stress, burnout and PTEOD will only increase as we are force-fed this diet of electronic overload without any reflection of what its doing to those who provide the care.

Ugh. I need another vacation.

-Wes

But it didn't take long after my return to work for me to feel flooded again. Two days after returning to work, it was like I never left. Perhaps it's like that for most busy folks, but somehow the world of health care delivery feels more frenetic than ever. The in-basket messages, the mountains of results, the re-scheduled patients on top of those already scheduled, the seemingly endless phone and e-mail messages, the late-night consults after a full day of procedures - all demanding time - it's bordering on crazy. I have several nurse practitioners who assist, but the volume of electronic patient care that's happening now is overwhelming to even the most computer-savvy of us doctors.

And all of this communication is not compensated. There are no "RVUs" for answering an e-mail. There are no "RVUs" for speaking on the phone. There are no "RVU's" for typing. No "RVUs" for data entry and clicking a mouse. Physician time means nothing to programmers and policy-makers.

It's a larger symptom, I think, of the new "efficiencies" built into the electronic medical record (EMR) that has become ubiquitous with the world of medicine today. Information flies so fast and there's so much of it that it's getting almost impossible for doctors to keep up with the screen responsibilities, not to mention their care responsibilities. The EMR is no longer just an EMR. The EMR has morphed into a scheduling agent, pharmacy, reminder pad, calculator, care pathway generator, instant-messaging service, a procedure orderer-by-proxy (and guideline) and a patient messaging portal that, aside from a 400-character limit, provides unprecedented access to physician in-boxes and schedules. There are so many buttons that they no longer fit on a single screen and the "allergy" field no longer can be displayed as it's pushed out of the way by the name of the patient's insurer. Add to this the constant and growing influx of patients (thanks to marketing pushes and programs to spur referrals), voluminous administrative meetings, and growing CME requirements, it's no wonder many of us feel flooded. I work later than ever now thanks to these electronic "efficiencies," then find myself waking in the middle of the night wondering: Did I call Ms. Smith? Did I miss something? Did I put that order in? When am I going to do those result notes?

I think I'm suffering from post-traumatic electronic overload disorder (PTEOD).

Oh sure, we could hire another guy or gal to offload some of the work - maybe even hire a wasteful manpower-intensive scribe like those that work in some ERs that click for cash - but that really won't help stem the ongoing barrage of information that is now pummeling physicians and their care teams at an unprecedented rate. Sadly, I don't see this trend changing anytime soon - the business case for the EMR is just too attractive for hospitals and payers. Still, with the prospect of ICD-10 and it's 71,924 procedure codes and 69,823 diagnosis codes (that must be paired correctly lest doctors not be paid) just around the corner, I fear that physician stress, burnout and PTEOD will only increase as we are force-fed this diet of electronic overload without any reflection of what its doing to those who provide the care.

Ugh. I need another vacation.

-Wes

Monday, March 03, 2014

When Regulators Pay for Peer-review

The ongoing controversy among US physicians over newly-implemented "Maintenance of Certification (MOC)" requirements created by the private organization, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and its 24 subsidiary subspecialty boards has breached another ethical front: paying for peer-reviewed publications in support of their expensive and proprietary MOC process.

In the Fall of 2013, the ABMS single-handedly funded an entire supplement devoted to the MOC process in the Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. This journal is published quarterly by the Alliance of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, the Society for Academic Continuing Medical Education, and the Council on CME of the Association for Hospital Medical Education. Not surprisingly, the articles published were uniformly favorable about the MOC process despite evidence to the contrary. The American Medical Association (who also stands to benefit from the process politically) was quick to provide a free link to the full pdf of the supplement from its AMA Wire news bulletin.

Interestingly, the literature review of the MOC process performed by Lipner et al. (page S20 of the supplement) admitted the limitations of their review:

I welcome the ABMS's response regarding their practice of paying for publications in support of the MOC process in the comment section of this blog.

-Wes

In the Fall of 2013, the ABMS single-handedly funded an entire supplement devoted to the MOC process in the Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. This journal is published quarterly by the Alliance of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, the Society for Academic Continuing Medical Education, and the Council on CME of the Association for Hospital Medical Education. Not surprisingly, the articles published were uniformly favorable about the MOC process despite evidence to the contrary. The American Medical Association (who also stands to benefit from the process politically) was quick to provide a free link to the full pdf of the supplement from its AMA Wire news bulletin.

Interestingly, the literature review of the MOC process performed by Lipner et al. (page S20 of the supplement) admitted the limitations of their review:

"First, we did not consider certification by other entities other than ABMS boards; these results may not generalize to other certification bodies. Second, we did not use a formal system to judge the quality of the methodology used in the studies. Third, a meta-analysis to compared effect sizes across different data types was not done; designs were extremely diverse, and it may not be possible with the information available."Given these limitations, the "value" of the MOC process, based on the data, is totally subjective. Despite these glaring limitations, the article concludes:

The main goal of certification is physician accountability to the public (editor: note that the "patient" and "doctor" are not mentioned). We have shown that a substantial body of evidence supports the value of certification and MOC in meeting that goal but the evidence is not unequivocal. In response, the ABMS have begun to enhance their programs to be more authentic and relevant to practice while maintaining their rigor and continuing to study the program's validity."If the way the ABMS "enhances" the value of its proprietary MOC process is to pay for peer-reviewed publications that ignore the serious limitations mentioned by the authors themselves, then those directly impacted by the MOC process (like myself) have an obligation to question the validity and ethics of the ABMS's self-promotional practice.

I welcome the ABMS's response regarding their practice of paying for publications in support of the MOC process in the comment section of this blog.

-Wes