As I begin another year teaching EKG's to our new residents, I find I am increasingly asking myself "Where to teach?"

I do not mean to imply a geographic sense to the word "where" (although this is difficult, too, as residents move from hospital to hospital in large health care systems like ours as they change rotations), but rather as more of a "level." What level do I teach our residents the art of EKG reading? Do I keep it rudimentary or do I teach it at the level of a good cardiology fellow? Are we striving for excellence or striving for adequacy in EKG interpretation? Said another way: do I teach at a Dubin's level of EKG interpretation or a Marriott's?

This is not an easy decision for those engaged in teaching medical students and residents.

Every year I am evaluated by the residents for my instruction, and every year I get good marks. But an e-mail received from our program director made me concerned, because a criticism they had heard from the residents was that my instruction was too advanced. (This was a first for me despite using similar core lecture materials year to year).

Which led me to wonder, is my curriculum too advanced for our newer residents or are medical students not receiving instruction on EKGs in medical schools before residency? Or has is the art of EKG interpretation evolving to simply reading the computer-generated interpretation at the top of the tracing? Should residents just be taught basic ACLS-level tracings or the more subtle findings of hypothermia and hypercalcemia?

I wonder why there's such a difference now, why there is a draw to spoon-feed our residents rather than to teach them basic principles upon which to grow their understanding. Perhaps residents are flooded. Perhaps they are scared. Or (more likely) perhaps we need to do a better job leading by example. Perhaps, as one fellow of mine said, our attendings in medical schools are so hurried to get back to clinic that they never do chalk-talks or EKG reading with residents any more. Maybe the pressures to make medicine more efficient is robbing from education.

Whatever it is, there is a change.

I'm sure I'm not the only teacher who's encountered the same difficulty knowing where to teach now. But I continue to believe that our youngest doctors can rise to any challenge they are given as long as they have enough time, so don't expect it to be any easier from now on, but maybe just a bit slower.

My time, after all, is unlimited. (* cough *)

-Wes

Friday, August 22, 2014

Friday, August 15, 2014

To the ABIM: What Real Life-long Learning Should Look Like

He left a little early to stop by the cath lab to see his patient before her procedure. Cordial "Hello's" and "Good mornings" and "Any last questions?" were mentioned before she signed her consent. The team was working feverishly to prepare her for her procedure. "Have you met the anesthesiologist yet?" was next, and almost on cue, the anesthesiologist arrived and took over for a bit.

He hurried upstairs to the conference room. There, was an all-too-fattening array of welcoming donuts and bagels, a coffee and hot water dispenser, and a few remaining empty cups. This was the stuff of breakfast on more hurried days. Still, a small cup of coffee was welcomed and poured quickly. Another nurse had arrived with him and he asked, "Can I pour you one?" She accepted and they quickly made their way into the conference room after signing the attendance sheet. They didn't want to miss the start of the conference for that was sometimes the best part of the conference.

In a stroke of genius, the organizers of the Cath Conference quickly review the news of the week, both locally, nationally, and medical. They even show wild things colleagues did the week before outside of conference, like flyboarding or a shot of a colleague holding a huge striped bass they caught the weekend before with their 8 year-old daughter. Complaints about the design of the restrospective trial reviewing digoxin's use for atrial fibrillation, sodium's uncertain consumption recommendations this week were met with rolled eyes, and the possibility of transcaval retrograde transaortic valve replacement in patients with no other access was discussed, with a quick aside of direct translumbar aortic punctures and even direct left atrial punctures being performed by surgeons in earlier times. In short, they shared the other side of themselves together, the reality of science, their humanness.

Then they shared cases.

The cases are not always pretty. Some were tough cases, wonderful cases, cases no one had seen before. They discuss the complicated social situations that bring even more complicated dynamics to the case. They discuss the errors and the complications. Importantly, they all understand this is a legally protected conference - a morbidity and mortality conference, if you will - a place where there are frank discussions about the right way to treat things and the wrong way, but a place that is supportive to those who have struggled, and incredibly helpful to those who still struggle with many challenges. Administration hears about the problems doctors had with the lab equipment or staff or whatever - professionally.

And it's the most popular conference in our hospital. People of all ages and technical backgrounds are welcomed. Old and young, cath lab staff, nurses, quality personnel, research staff, administrators, guest speakers, cardiologists and surgeons. Everyone, that is, except industry or pharmaceutical folks. This is, after all, the work of health care, not marketing.

At the end, they greeted, however briefly. A quick question is asked. A consult requested. A research form signed. Then off they went on their ways for another week to do their jobs.

This is lifelong learning as it should be: cordial, professional, collaborative, fulfilling, timely, up to date, and self-generated. And it happens because it has to, not because it's directed by a centralized bureaucratic money-making organization who claims they know what's best for doctors and what's best for society.

When doctors, nurses, technologists and health care teams learn this way it's sustainable for a lifetime for one simple reason:

... because it's enjoyed.

-Wes

He hurried upstairs to the conference room. There, was an all-too-fattening array of welcoming donuts and bagels, a coffee and hot water dispenser, and a few remaining empty cups. This was the stuff of breakfast on more hurried days. Still, a small cup of coffee was welcomed and poured quickly. Another nurse had arrived with him and he asked, "Can I pour you one?" She accepted and they quickly made their way into the conference room after signing the attendance sheet. They didn't want to miss the start of the conference for that was sometimes the best part of the conference.

In a stroke of genius, the organizers of the Cath Conference quickly review the news of the week, both locally, nationally, and medical. They even show wild things colleagues did the week before outside of conference, like flyboarding or a shot of a colleague holding a huge striped bass they caught the weekend before with their 8 year-old daughter. Complaints about the design of the restrospective trial reviewing digoxin's use for atrial fibrillation, sodium's uncertain consumption recommendations this week were met with rolled eyes, and the possibility of transcaval retrograde transaortic valve replacement in patients with no other access was discussed, with a quick aside of direct translumbar aortic punctures and even direct left atrial punctures being performed by surgeons in earlier times. In short, they shared the other side of themselves together, the reality of science, their humanness.

Then they shared cases.

The cases are not always pretty. Some were tough cases, wonderful cases, cases no one had seen before. They discuss the complicated social situations that bring even more complicated dynamics to the case. They discuss the errors and the complications. Importantly, they all understand this is a legally protected conference - a morbidity and mortality conference, if you will - a place where there are frank discussions about the right way to treat things and the wrong way, but a place that is supportive to those who have struggled, and incredibly helpful to those who still struggle with many challenges. Administration hears about the problems doctors had with the lab equipment or staff or whatever - professionally.

And it's the most popular conference in our hospital. People of all ages and technical backgrounds are welcomed. Old and young, cath lab staff, nurses, quality personnel, research staff, administrators, guest speakers, cardiologists and surgeons. Everyone, that is, except industry or pharmaceutical folks. This is, after all, the work of health care, not marketing.

At the end, they greeted, however briefly. A quick question is asked. A consult requested. A research form signed. Then off they went on their ways for another week to do their jobs.

This is lifelong learning as it should be: cordial, professional, collaborative, fulfilling, timely, up to date, and self-generated. And it happens because it has to, not because it's directed by a centralized bureaucratic money-making organization who claims they know what's best for doctors and what's best for society.

When doctors, nurses, technologists and health care teams learn this way it's sustainable for a lifetime for one simple reason:

... because it's enjoyed.

-Wes

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

Data Plan Health Care Shows Promise

CHICAGO - Citing mounting health care costs, electronic note bloat, and concerns with the quality and quality of Big Data, IBM, Apple, and EPIC Systems recently announced a new initiative to totally revamp US health care by offering health care services by data plan. The health care initiative was recently discovered in a little known section of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) that changed portions of the U.S. Tax Code.

Under the new system, the brainchild of prominent Chicago physician-turned-health care entrepreneur Henry Throckmorton, MD, patients will purchase an initial 250 megabytes of data space on the EMR for all their health needs for $250 per month. “It’s cheaper than most current cell phone service," Throckmorton explained. "When patients exceed their data allotment, health care ceases until patients purchase an additional data storage plan." Expansion data plans come in Bronze (250 M Bytes), Silver (500 Mbytes), Gold (5 G Byte), and Platinum (10 GB) storage increments.

Rollover plans for family members are also offered for those nearing the end of life.

“Health care systems that promise to limit the use of macros, dot phrases and cut-and-paste tactices have a real competetive advantage over competitors insensitive to the patient's data needs!” Throckmorton explained. "This system finally puts health care incentives in the right place.”

But Roger Wilco, spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), the national trade association representing the health insurance industry, seemed less enthusiastic. "This is preposterous! Who do these flowery internet types think they are? Don't they realize there are advantages to more middle men in health care? How are we supposed to get our cut of the money?"

Dr. I.P. Knightly of Urocare Health System in Beaverton, New York, seemed less concerned about the middlemen and appreciated the improvements he's seen in patient care: “Because I document everything on the EMR, including phone calls, results and work schedules, patient are less likely to call so I get a good night’s sleep!”

Nursing and medical students seem torn, however. While some see benefits to shorter notes, some like Tim Allen, MD, a hard-working fourth-year medical student from Roanoke, VA, sees other challenges “I’m still trying to understand ortho notes that no longer contain the critical information fields like the patient’s full name, VIP status, research status, and a complete review of systems. How's a guy supposed to understand what ‘Silt @ t/s/s/sp/dp’ means?”

Market analyst Rebecca Solomon of Lock, Stock and Barrel Equity Partners noted "Apple, IBM and EPIC are quickly gaining market share from more conventional insurance policies. The concept has also resonated with the Department of Health and Human Services because of the cost savings seen from fewer data-hungry imaging studies being ordered."

Mobile partnerships with AT&T, Verizon, and T-mobile are planned in the next fiscal year.

* * *

-Wes

P.S.: If you thought this press release might be real, even for a second, consider why.

Maintenance of Certification: Beauty Is in the Eyes of the Beholder

This must-read paper from Drs Centor, Fleming and Moyer was recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. While it does not pertain to specialists, it serves as a level-headed rebuttal to the positive perspective of the Maintenance of Certification program (MOC) developed and marketed by the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Medical Specialties:

-Wes

Reference: Centor RM, Fleming DA,and Moyer, DV. "Maintenance of Certification: Beauty Is in the Eyes of the Beholder" from Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(3):226-227. doi:10.7326/M14-1014

While these authors' polite critique of the ABIM's method of assessing fellow physicians makes excellent points, we should still question the relevance of such a system for specialitist, especially for those who gain clinical and surgical experience over time. Furthermore, the MOC requirement that requires the performance of research on physicians using unscientifically validated patient surveys fails to afford doctors the most basic research protections created after the unintended consequences of similar well-meaning government research programs came to light. To ignore these additional shortcomings of the ABIM's MOC process should not be tolerated by any practicing member of our profession."There are no facts, only interpretations."

—Friedrich Nietzsche

In this issue, Baron and Johnson (1) describe the history of and rationale for the creation of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and recent changes in maintenance of certification (MOC). They focus on setting standards and identifying “good doctors” who meet those standards. By implication, those who do not participate or are unsuccessful in achieving recertification are substandard. Although the ABIM is clearly proud of the MOC process that it has developed, many internists find it a source of great distress.

We suggest considering a basic observation in cognitive psychology, the affect heuristic, as a construct to help understand the disconnect between the ABIM's and internists' views of MOC (2–3). According to this heuristic, when we like a thing or an idea, we overestimate the benefits and underestimate the risks or unintended consequences. If we dislike something, we underestimate the benefits and overestimate the risks.

Those invested in developing the MOC process seem to highlight potential benefits and minimize possible unintended consequences. We have deep concerns that this well-intended policy will, indeed, cause negative consequences for physicians and society.

Over the past several months, we have heard from many internists about the MOC process. These physicians have a wide variety of training and experience and include well-trained, insightful, and skilled internists who share a commitment to maintaining high standards of professional performance. Yet, their concerns over the new demands that the MOC process entails are palpable. Their focus is on the potential unintended consequences, and they are struggling to acknowledge the potential benefits. When these physicians talk with us about MOC, frustration and dismay about the process dominate the conversations.

Internists feel increasing pressure from many directions. Time is an entity that none of us can recoup, and internists appropriately raise concerns about growing time pressures on all fronts (4). They are experiencing increasing administrative burdens that limit their ability to provide the type of patient care that they want to deliver.

These burdens include issues related to usability and interoperability of electronic health records, complex documentation requirements, growing requirements for prior authorization of the tests and treatments that they prescribe, and a payment system that does not recognize the time and effort that they spend on telephone or e-mail communication. The new MOC requirements add to this burden by being time-consuming and costly and having unclear benefits on patient care. Added to these concerns is a high-stakes, secure recertification examination whose first-time failure rate has increased from 10% to 22% over the past 5 years.

Although most first-time recertifying examinees who fail eventually pass the examination, they suffer distress and additional cost to retake it. Internists, like all physicians, want to bring their best, evidence-based practice to every patient every day. They want to test their knowledge and better their practices in a formative way to improve patient care and outcomes.

We worry that the ABIM may focus too much on metrics, administrative processes, and finding the “substandard doctors” who theoretically place the public at risk and too little on the design and implementation of a process that encourages ongoing education and professional development. The implication is that MOC will allow for better policing of “bad” internists rather than helping us all be “better” internists. We believe that the ABIM's stated accountability to the profession, which accompanies its accountability to the public, should lead to better recognition of dissatisfaction among its diplomates and a more collaborative approach with internal medicine specialty and subspecialty societies to address this dissatisfaction.

Unfortunately, the new MOC process has become the straw that broke the camel's back in many internists' minds. They dislike each part of the process but seem most angry about the practice improvement modules and secure examination. They see the first as “busy work” and the second as lacking relevance to their personal practice and to how medicine is currently practiced. The present structure of the summative secure examination of the ABIM does not provide specific feedback to facilitate this process let alone reflect the current state of practice, namely, collaboration in patient care and real-time engagement of evidence-based resources.

Any physician evaluation process should consider the practical wisdom, knowledge, and skill necessary to be a good practicing physician and test how those attributes are actually used in patient care. Fostering the development of phronesis (practical wisdom) in physicians through the effective and safe use of knowledge and skill in the clinical moment allows us to fulfill the covenant we have with patients and the contract we have with society.

Our internist colleagues tell us that they embrace the importance of remaining current, but they do not believe that the current MOC process helps them achieve that goal. As currently implemented, MOC involves substantial time, and internists believe that time supersedes more educationally sound activities. Current learning theory supports the use of testing to guide further learning and the provision of educational tools to address knowledge weaknesses.

Testing for knowledge alone does not determine how skilled and effective an internist is at the bedside, in history-taking, and in performing a targeted physical examination. Would it not be better and more practical to have a testing process that assesses the ability to gather and interpret information and that encompasses the entire clinical encounter? Can the MOC process as it stands truly evaluate our ability to deliver patient-centered care?

Too many internists view “professional self-regulation” as currently conceived by the ABIM to be a nonproductive and often punitive experience. All too often, they see regulatory bodies as depleting money, time, and joy from their professional lives. Further, many do not believe that burdensome processes being forced on them will benefit their patients or their professional lives. Thus, it should be no surprise that internists focus on the direct and indirect costs of MOC rather than on the potential benefits that are the focus of the current commentary of the ABIM leaders.

We recognize the ABIM's good intent and the substantive challenges of developing an effective assessment process that ensures a corps of good internists. Unfortunately, too many internists find some aspects of the current process lacking at a time when concerns about the ramifications of this high-stakes professional endeavor are increasing.

-Wes

Reference: Centor RM, Fleming DA,and Moyer, DV. "Maintenance of Certification: Beauty Is in the Eyes of the Beholder" from Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(3):226-227. doi:10.7326/M14-1014

The Tradeoffs of Obamacare

A few from above, from Saurabh Jha, MD (Twitter: @roguerad):

-Wes

The biggest trade-off is between a constitutional republic, with all its checks and balances, and a centrally-planned healthcare. The two are fundamentally incompatible. The future will yield many more convulsions. Many more Halbigs.Read the whole thing.

The optimism surrounding the ACA, summed up by President Obama's promise "if you like your doctor, you can keep your doctor," gave many the impression, myself included, that healthcare reform can be Pareto optimal; a win-win for all.

Regrettably, trade-offs are a fact of life. Which means there are winners and there are losers. This is not unusual. But by not acknowledging the trade-offs we have created resentment in the losers, and widened the partisan chasm.

-Wes

Sunday, August 10, 2014

From the Mouths of Babes

"Dad, you have the nicest patients!"

She was right, of course. Daughters that you bring to work with you to shadow for a day can bring you back to what's important in medicine. In fact, seeing medicine through fresh eyes is helpful, especially when we forget to look up from our work-a-day lives.

It had been over ten years since I had my first "Bring Your Daugher to Work" experience. Her first time she wore scrubs they were bigger than she was. She always remembered that day.

It had been over ten years since I had my first "Bring Your Daugher to Work" experience. Her first time she wore scrubs they were bigger than she was. She always remembered that day.

There probably won't be too many more times we'll share such an experience together. Like most young college kids she's growing her own life now, trying to decide what to do.

"Why not shadow me and my nurse practitioner for a day to see what think? I have a light day, you could really see what we do first-hand!"

Much to my surprise, she agreed. And so we spent the entire day together once more.

She saw everything I did but this time with a more critical eye. She saw everything my nurse practitioner did, too. Just in case. She witnessed the miracle of anesthesia, a strangeness of the "time-out," then the jolt of a cardioversion. She saw the smile of the patient after it was all over. She saw the real discourse that occurs between colleagues that are used to working with each other. She saw the computer. She saw the EKG. She saw the family discussion afterward. Everything.

Perhaps most touching was the moment we walked into a long-time patient's room - a fellow doctor - and there he was, lying in bed with his ankles too swollen with his wife, daughter, and granddaughters by his side. His eyes, while a bit sunken, were beaming when he saw me.

"I'd like to introduce you you my family!" he exclaimed. And one by one he introduced me to his lovely wife, daughter, and granddaughters who had all come to spend some time with him. Of course, I couldn't resist, and similarly gushed, "I'd like to introduce you to a member of my family, too!" I proudly introducing my daughter to him and the rest of his extended family. His grandaughters were slightly younger than my daughter - just starting to think about college. My daughter, now a veteran of the college experience, offered some words of encouragement to them. They graciously nodded. I couldn't help but marvel how therapeutic that interaction was for both of us - doctor and patient - a way to bring our lives a bit closer, our understanding, more meaningful. Medicine is like that sometimes: one minute you're there to help the patient then you realize how much, in their grace, they help you.

I pretended not to think about this as I checked his defibrillator. "Working fine," I told him. He glanced at me and said "thank you" in a way I'll never forget: non-verbally with his eyes, as if to say, "I know how you're feeling."

We left the room and returned to the nurse's station - or maybe it should be called the "Computer Terminal Station," since doctors, pharmacists, physical therapists were all playing a game of musical chairs waiting for a terminal to open. More typing and staring at screens, more phone messages, documentation, lab checks, more typing, all clicked as fast as possible. Finally, after seeing more patients and typing more notes, we had a debriefing. Relaxed and looking forward to heading home, I asked her: "So what did you think?"

"You know, Dad, it was wonderful. Your patients are all so nice. But..."

There was a moment of hesitation in her voice, a concern, as she wrestled with how to break the news to me slowly; I could tell she didn't want to disappoint me.

"What is it?" I asked.

"... there's just so much typing!"

-Wes

She was right, of course. Daughters that you bring to work with you to shadow for a day can bring you back to what's important in medicine. In fact, seeing medicine through fresh eyes is helpful, especially when we forget to look up from our work-a-day lives.

It had been over ten years since I had my first "Bring Your Daugher to Work" experience. Her first time she wore scrubs they were bigger than she was. She always remembered that day.

It had been over ten years since I had my first "Bring Your Daugher to Work" experience. Her first time she wore scrubs they were bigger than she was. She always remembered that day.There probably won't be too many more times we'll share such an experience together. Like most young college kids she's growing her own life now, trying to decide what to do.

"Why not shadow me and my nurse practitioner for a day to see what think? I have a light day, you could really see what we do first-hand!"

Much to my surprise, she agreed. And so we spent the entire day together once more.

She saw everything I did but this time with a more critical eye. She saw everything my nurse practitioner did, too. Just in case. She witnessed the miracle of anesthesia, a strangeness of the "time-out," then the jolt of a cardioversion. She saw the smile of the patient after it was all over. She saw the real discourse that occurs between colleagues that are used to working with each other. She saw the computer. She saw the EKG. She saw the family discussion afterward. Everything.

Perhaps most touching was the moment we walked into a long-time patient's room - a fellow doctor - and there he was, lying in bed with his ankles too swollen with his wife, daughter, and granddaughters by his side. His eyes, while a bit sunken, were beaming when he saw me.

"I'd like to introduce you you my family!" he exclaimed. And one by one he introduced me to his lovely wife, daughter, and granddaughters who had all come to spend some time with him. Of course, I couldn't resist, and similarly gushed, "I'd like to introduce you to a member of my family, too!" I proudly introducing my daughter to him and the rest of his extended family. His grandaughters were slightly younger than my daughter - just starting to think about college. My daughter, now a veteran of the college experience, offered some words of encouragement to them. They graciously nodded. I couldn't help but marvel how therapeutic that interaction was for both of us - doctor and patient - a way to bring our lives a bit closer, our understanding, more meaningful. Medicine is like that sometimes: one minute you're there to help the patient then you realize how much, in their grace, they help you.

I pretended not to think about this as I checked his defibrillator. "Working fine," I told him. He glanced at me and said "thank you" in a way I'll never forget: non-verbally with his eyes, as if to say, "I know how you're feeling."

|

| Our "selfie" that day |

We left the room and returned to the nurse's station - or maybe it should be called the "Computer Terminal Station," since doctors, pharmacists, physical therapists were all playing a game of musical chairs waiting for a terminal to open. More typing and staring at screens, more phone messages, documentation, lab checks, more typing, all clicked as fast as possible. Finally, after seeing more patients and typing more notes, we had a debriefing. Relaxed and looking forward to heading home, I asked her: "So what did you think?"

"You know, Dad, it was wonderful. Your patients are all so nice. But..."

There was a moment of hesitation in her voice, a concern, as she wrestled with how to break the news to me slowly; I could tell she didn't want to disappoint me.

"What is it?" I asked.

"... there's just so much typing!"

-Wes

Wednesday, August 06, 2014

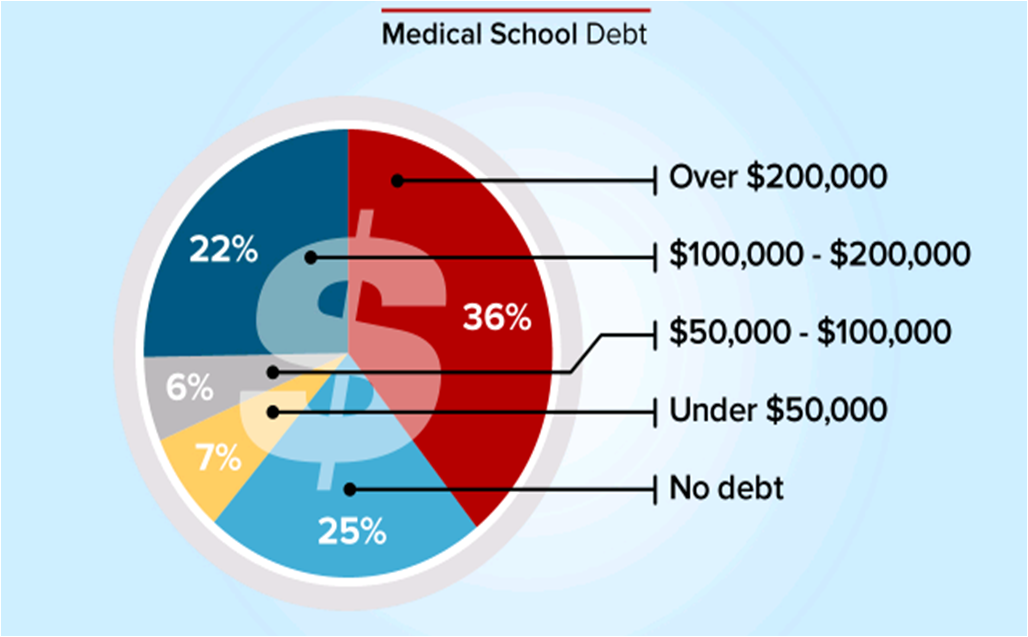

Medscape: 36% of Residents Have Over $200,000 Debt

From Medscape:

The same article quotes the average resident salary as $55,300. The actual "take-home"pay for residents is actually much lower and must be calculated for the state in which the doctor practices. For this, I turned to PayCheckCity.com's salary calculator.

Taking the $55,300 salary for a single doctor in Illinois, the weekly pay is $1063.46. From this comes the Federal withholding ($175.36), Social Security withholding ($65.93), Medicare withholding ($15.42), and Illinois witholding ($53.17), leaving $753.58 per week in income ($18.84 / hour for a 40-hour work week).

Now, if we just look at a monthly payment at 4.5% interest on a (conservative) $200,000 thirty-year loan, the monthy payment comes to $836.03. It becomes apparent that medical residents will have to work more than 8 days a month to just paying off their medical school loans.

More cheap money offered to residents in the form of new loans won't help this problem, it will only make things worse.

With the average public medical school tuition exceeding $207,000 and the average private medical school tuition exceeding $270,000, the joy of doctoring will quickly lose its luster for tomorrow's doctors-in-training.

And this crisis promises to only get larger for tomorrow's physicians.

For those planning on medical school, you might want to consider other sources of funding for your education. While the Navy had its drawbacks, at least I left medical school with $0 debt.

-Wes

The same article quotes the average resident salary as $55,300. The actual "take-home"pay for residents is actually much lower and must be calculated for the state in which the doctor practices. For this, I turned to PayCheckCity.com's salary calculator.

Taking the $55,300 salary for a single doctor in Illinois, the weekly pay is $1063.46. From this comes the Federal withholding ($175.36), Social Security withholding ($65.93), Medicare withholding ($15.42), and Illinois witholding ($53.17), leaving $753.58 per week in income ($18.84 / hour for a 40-hour work week).

Now, if we just look at a monthly payment at 4.5% interest on a (conservative) $200,000 thirty-year loan, the monthy payment comes to $836.03. It becomes apparent that medical residents will have to work more than 8 days a month to just paying off their medical school loans.

More cheap money offered to residents in the form of new loans won't help this problem, it will only make things worse.

With the average public medical school tuition exceeding $207,000 and the average private medical school tuition exceeding $270,000, the joy of doctoring will quickly lose its luster for tomorrow's doctors-in-training.

And this crisis promises to only get larger for tomorrow's physicians.

For those planning on medical school, you might want to consider other sources of funding for your education. While the Navy had its drawbacks, at least I left medical school with $0 debt.

-Wes

ABIM Placates Physician Anti-MOC Sentiment with "Commitments"

From the 5 Aug 2014 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC):

Provide a 1-year grace period for those who have attempted but failed to pass the secure examination.

We can only imagine what this means. Does it mean your name won't be posted on the ABMS's Wall of Shame for a year so you can attempt to take the test twice more? Nowhere is there a concern for the lost revenue, additional hours of study, psychological stress, and damage to a physician's professional reputation created by this unproven process. While the ABIM acknowledges the increasing failure rate of their examinations in their "letter" to the Internal Medicine community, they provide no evidence of critical self-apprraisal nor a viable rationale for this. Instead, the spin is that doctors should feel grateful they were granted a 1-year grace period to complete the MOC testing.

Update its governance and financial information on its website.

Updating a website does not mean change in governance will occur at the ABIM. All ABIM members should be elected by physician peers, not selected by ABIM members themselves. Is this what they mean? Of course not. Do we really think these back-slapping chums will change their self-serving ways? The fact that ABIM members "exercise ultimate fiduciary responsibility and authority" is not acceptable to professionals whose livelihoods are placed at risk by ABIM members who remain unaccountable to those they regulate. Until physicians have an active voice in the ABIM's "governance," this organization's professional credibility will remain suspect.

Regarding the financial information they will disclose: How will they justify the high salaries of the executives of the member boards that exceed the salaries of the doctors they pretend to represent by many times? Will they insist on the disclosure of all conflicts of interest and income gained as consultants? So far, the ABIM has failed to list the transfers of funds between organizations like the ABIM and it's separate "ABIM Foundation" publicly. Shouldn't all financial and societal relationships with the ABMS, AMA, ACP, CMS, National Quality Forum, AMA's legal team, academic centers, the American Hospital Association, insurers and other "stakeholders" eager to use the ABIM's data trove be disclosed as well? Will the ABIM disclose how the survey and test data collected on their server is protected, sold and/or shared? Why is this unproven MOC process being promoted as a measure of physician "quality?" Why has it been allowed to continue as a Medicare physician payment incentive? Given these problems with fiscal transparency, why does our government collude with this private entity? If the ABIM's "governance and financial information" fails to change sufficiently or mention these specifics, physicians and the public have gained very little from any "commitments" promised by the ABIM.

Ensure a broader range of CME options for medical knowledge and skills self-assessment (Part II).

This is really not a concern, so why it was included as an "action item" for the ABIM is uncertain. Physicians have always had many ways to earn continuing medical education (CME) credits that do NOT involve the ABIM's MOC process and these MUST be preserved. Physicians to not want the ABIM to monopolize their ability to gain CME from other sources or methods, especially when the ABIM commands repeated high payments from physicians for their products.

Provide more feedback regarding test scores.

"Feedback" can come in many ways: statistics, providing answers, or maybe even disclosing a passing level. But let's be honest. Why do we care? Especially when failing still has significant employment, credentialing and social ramifications. Isn't the point to of life-long-learning to educate? Isn't the point to learn? Is forcing doctors to take a computerized test in a secure prison-like environment really beneficial to patients, or just a means of making subordinates of clinical professionals? Why do we physicians continue to allow such a punitive means for assessment to take hold when there is no independently validated evidence that MOC does anything to improve patient care?

Evolve the “patient survey” requirement to a “patient voice” requirement and increase the number of ways this requirement can be met.

Oh my goodness. Really? A "patient voice" requirement rather than a "patient survey?" The ABIM really has no idea whom they are serving. They have a Utopian vision for themselves: as one Great Overseer of All Things Perfect and to define for both doctors and "the Public" (whoever they feel that comprises) what "voice" we should all hear. I can see it now: patient's flying in a horrible thunderstorm with their doctor piloting the plane and the ABIM's answer to improving the safety of the flight? Make sure the patient's have a "voice" or let's pass out a "survey!" The reality today is that patients have a voice in their health care: they can go elsewhere, they can sue, they can critique their doctors publicly. To suggest that patients need a "voice" in assuring physician competency, courtesy of the ABIM's expensive MOC requirement, is not only patronizing, but insulting to both patients and doctors.

Reduce the data collection requirement for the practice assessment requirement; utilizing performance improvement activities already in place and minimizing the time and complexity of data input.

This is nothing new. It already existed and is exactly what I did recently in my recent recertification process in 2013.

Investigate changes in the secure examination to increase relevance with specific attention to exploring applications for practice focus areas (“modular examinations”) and open-book examinations.

This sounds like a Carte Blanche idea to expand the ABIM's reach and costs without oversight. Who will fund such an initiative? Who will regulate the spending of these self-imposed regulators? How can we control costs of this whole process when the process is continually expanded with such unrealistic and grandiose ideas? Isn't medicine and real life already an "open book test" for today's physicians? Why do we need the pleasure of paying $750 or even more for a another secure exam in a videotaped office building that prides itself on cavity searches? This whole process is already out of hand. Cut it back and make it manageable, don't expand it.

Why should anyone care about all of this? Yesterday morning, my good friend John Mandrola, MD sent a prescient tweet my way:

After all, actions speak louder than words.

-Wes

Addendum: If you've failed a recent Maintenance of Certification examination, I am still confidentially collecting stories from affected physicians. Please consider contributing yours.

"Note: There is evidence that the ABIM has heard the concerns of its diplomats and is acting responsively. In a July 10, 2014 letter to the internal medicine community, and in a face-to-face meeting in Philadelphia on July 15, 2014, which was attended by 26 internal medicine subspecialty societies including the ACC, the ABIM committed to:

- •Provide a 1-year grace period for those who have attempted but failed to pass the secure examination.

- •Update its governance and financial information on its website.

- •Ensure a broader range of CME options for medical knowledge and skills self-assessment (Part II).

- •Provide more feedback regarding test scores.

- •Evolve the “patient survey” requirement to a “patient voice” requirement and increase the number of ways this requirement can be met.

- •Reduce the data collection requirement for the practice assessment requirement; utilizing performance improvement activities already in place and minimizing the time and complexity of data input.

- •Investigate changes in the secure examination to increase relevance with specific attention to exploring applications for practice focus areas (“modular examinations”) and open-book examinations.

It is concerning that the ACC leadership feels the ABIM is "acting responsively" and continues to market the MOC proess so aggressively. Let's critically review the list of proposed ABIM "commitments" outlined above:For its part, the ACC has recently:

- •Released a special video that catalogs the suite of ACC resources available to help members meet the MOC Part IV requirements.

- •Determined that free-standing MOC modules will be offered to ACC members at no charge.

- •Posted online (CardioSource.org/MOC) a comprehensive list of ACC MOC Part II offerings. New modules will be added as they become available."

Provide a 1-year grace period for those who have attempted but failed to pass the secure examination.

We can only imagine what this means. Does it mean your name won't be posted on the ABMS's Wall of Shame for a year so you can attempt to take the test twice more? Nowhere is there a concern for the lost revenue, additional hours of study, psychological stress, and damage to a physician's professional reputation created by this unproven process. While the ABIM acknowledges the increasing failure rate of their examinations in their "letter" to the Internal Medicine community, they provide no evidence of critical self-apprraisal nor a viable rationale for this. Instead, the spin is that doctors should feel grateful they were granted a 1-year grace period to complete the MOC testing.

Update its governance and financial information on its website.

Updating a website does not mean change in governance will occur at the ABIM. All ABIM members should be elected by physician peers, not selected by ABIM members themselves. Is this what they mean? Of course not. Do we really think these back-slapping chums will change their self-serving ways? The fact that ABIM members "exercise ultimate fiduciary responsibility and authority" is not acceptable to professionals whose livelihoods are placed at risk by ABIM members who remain unaccountable to those they regulate. Until physicians have an active voice in the ABIM's "governance," this organization's professional credibility will remain suspect.

Regarding the financial information they will disclose: How will they justify the high salaries of the executives of the member boards that exceed the salaries of the doctors they pretend to represent by many times? Will they insist on the disclosure of all conflicts of interest and income gained as consultants? So far, the ABIM has failed to list the transfers of funds between organizations like the ABIM and it's separate "ABIM Foundation" publicly. Shouldn't all financial and societal relationships with the ABMS, AMA, ACP, CMS, National Quality Forum, AMA's legal team, academic centers, the American Hospital Association, insurers and other "stakeholders" eager to use the ABIM's data trove be disclosed as well? Will the ABIM disclose how the survey and test data collected on their server is protected, sold and/or shared? Why is this unproven MOC process being promoted as a measure of physician "quality?" Why has it been allowed to continue as a Medicare physician payment incentive? Given these problems with fiscal transparency, why does our government collude with this private entity? If the ABIM's "governance and financial information" fails to change sufficiently or mention these specifics, physicians and the public have gained very little from any "commitments" promised by the ABIM.

Ensure a broader range of CME options for medical knowledge and skills self-assessment (Part II).

This is really not a concern, so why it was included as an "action item" for the ABIM is uncertain. Physicians have always had many ways to earn continuing medical education (CME) credits that do NOT involve the ABIM's MOC process and these MUST be preserved. Physicians to not want the ABIM to monopolize their ability to gain CME from other sources or methods, especially when the ABIM commands repeated high payments from physicians for their products.

Provide more feedback regarding test scores.

"Feedback" can come in many ways: statistics, providing answers, or maybe even disclosing a passing level. But let's be honest. Why do we care? Especially when failing still has significant employment, credentialing and social ramifications. Isn't the point to of life-long-learning to educate? Isn't the point to learn? Is forcing doctors to take a computerized test in a secure prison-like environment really beneficial to patients, or just a means of making subordinates of clinical professionals? Why do we physicians continue to allow such a punitive means for assessment to take hold when there is no independently validated evidence that MOC does anything to improve patient care?

Evolve the “patient survey” requirement to a “patient voice” requirement and increase the number of ways this requirement can be met.

Oh my goodness. Really? A "patient voice" requirement rather than a "patient survey?" The ABIM really has no idea whom they are serving. They have a Utopian vision for themselves: as one Great Overseer of All Things Perfect and to define for both doctors and "the Public" (whoever they feel that comprises) what "voice" we should all hear. I can see it now: patient's flying in a horrible thunderstorm with their doctor piloting the plane and the ABIM's answer to improving the safety of the flight? Make sure the patient's have a "voice" or let's pass out a "survey!" The reality today is that patients have a voice in their health care: they can go elsewhere, they can sue, they can critique their doctors publicly. To suggest that patients need a "voice" in assuring physician competency, courtesy of the ABIM's expensive MOC requirement, is not only patronizing, but insulting to both patients and doctors.

Reduce the data collection requirement for the practice assessment requirement; utilizing performance improvement activities already in place and minimizing the time and complexity of data input.

This is nothing new. It already existed and is exactly what I did recently in my recent recertification process in 2013.

Investigate changes in the secure examination to increase relevance with specific attention to exploring applications for practice focus areas (“modular examinations”) and open-book examinations.

This sounds like a Carte Blanche idea to expand the ABIM's reach and costs without oversight. Who will fund such an initiative? Who will regulate the spending of these self-imposed regulators? How can we control costs of this whole process when the process is continually expanded with such unrealistic and grandiose ideas? Isn't medicine and real life already an "open book test" for today's physicians? Why do we need the pleasure of paying $750 or even more for a another secure exam in a videotaped office building that prides itself on cavity searches? This whole process is already out of hand. Cut it back and make it manageable, don't expand it.

Why should anyone care about all of this? Yesterday morning, my good friend John Mandrola, MD sent a prescient tweet my way:

Yet another of Louisville's finest docs sends letter of resignation. Experienced docs are leaving in droves. No one is secure. @doctorwesSenior doctors are getting tired of all the nonsense in medicine these days. And nowhere is there more nonsense that the ABIM's complicated Maintenance of Certification program. Their continuing education program is far too cumbersome, onerous, and expensive and supplies little to no marginal utility for patients relative to the care that their physicians provide. As a result, the ABIM's MOC process is causing more harm than good to patient care while also compromising physician retention. Unless this is horrible mess is greatly simplified or stopped all together, look for more and more doctors to move on to other less hostile work environments or to simply retire.

— John Mandrola, MD (@drjohnm) August 5, 2014

After all, actions speak louder than words.

-Wes

Addendum: If you've failed a recent Maintenance of Certification examination, I am still confidentially collecting stories from affected physicians. Please consider contributing yours.