I probably shouldn't be writing this.

Tomorrow, after all, I sit for my Maintenance of Certification examination in Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology. It's my second time re-certifying after passing my original EP boards in 1994. And as I've been learning, things have changed. But I should do fine, right? There's no need to worry, right? I've been doing this my whole working life after all.

Relax, Wes!

But I do worry. That is my nature. I have spent countless hours worrying about this test. II took the sanctioned Heart Rhythm Society Board Review Course to prepare for this test. Why? Because I know from prior experience that there are tricks to these tests: certain topics that always get tested. The directors of these courses, sworn to secrecy mind you, give you clues what will be on these tests by the material they cover in their lectures. So I paid. Yeah, it's a racquet and I'm probably a fool, but knowing how to spend your precious time studying after a full's day work is helpful. After all, it would be embarrassing and even more costly for me if I do not pass.

So, for whatever reason, I just don't want to forget how I feel right now. Perhaps it's to let my patients know why their clinic date with me has been bumped. Perhaps it's to let others know what one doctor really feels just before doing this so late in one's career.

But honestly, I suppose I really want to write this post for me. I don't want to lose the memory of what it was like to watch the video about the unfamiliar corporate testing center where I must go, about the infra-red palm reader that I will have to use to prove the person there is really me. I don't want to forget the guy (or gal) that will be sitting behind the glass wall watching me as I sit staring at a wall and a computer screen in a tiny cubicle clicking at a keyboard for eight hours. I don't want to forget that even my watch and wallet won't be allowed in the room; that I will be unreachable in this tomb. I don't want to forget the foreboding sense of a robotic depersonalization; about my anxiety at the thought of constantly worrying about a tiny digital clock in the right upper corner of the screen constantly ticking, ticking, ticking - as if medical decisions are ever timed like this. Like Nineteen Eighty-Four.

And I especially don't want to forget how incredibly small I feel as doctor now...

... the day before.

-Wes

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Saturday, October 26, 2013

Friday, October 25, 2013

With Obamacare: Remember the Challenger

By now, the Obamacare insurance exchange debacle is old news. Our attention spans are so short, we're on to the next disaster. So we sit before our TVs and enjoy the Humana ads with a smiling senior pointing to a whiteboards with their insurance plan name, or watch the news sponsored by Unitedhealth or Walmart's pharmacy department. Everyone's got a cheaper plan these days with more benefits than the other guy, and the good news never ends for you, according to our insurance companies.

Sign up people. No worries.

Even if they take you to the cleaners.

It was interesting reading the piece over at Kaiser Health News asking why a couple without kids has to buy dental insurance for children they don't have. Or the free colonoscopy "catch" never discussed in the Obamacare ads that promoted by the law's proponents. More and more of these not-so-little details are not as pretty and "free" as everyone had hoped, but it's what we as a nation have approved, hidden in the new law we never read.

Shame on us.

Shame on our legislators.

But we must take a different perspective now that it's becoming crystal clear what central control of health care delivery means. I think most Americans have been incredibly tolerant of the rollout (and even appreciate the effort involved) since they have a rudimentary understanding of how complicated health care has become in America and how vital it is to our economy.

But I sense (like many others) that Americans' patience is growing thin. People are wondering how will things be fixed? How long will it take? Will I have to pay a penalty for something so fraught with problems? Who's responsible? Whom can I call? Can they be trusted? Is this going to be how the rest of the health care coverage rollout happens?

Years ago, millions of people watched the US space shuttle Challenger explode into a million tiny pieces on a crystal clear day shortly after its launch. We were shocked at first, then deeply saddened, for our idealized notion of the space program so advanced and amazing quickly evaporated before our eyes. We grieved with the crew's families as we watched in horror the events replayed on TV again and again and again.

But then what happened? Investigations followed. Video tapes were reviewed. A root cause analysis was undertaken. Ideas were tested, the O-ring problem identified, and slowly, carefully, changes were made to the shuttle program. New parts were engineered, other parts scraped. More thorough testing than ever before occurred. Then re-testing. And slowly, cautiously, the shuttle program resumed, one baby step at a time.

And no one ever took a complicated shuttle launch for granted again.

So, too, should it be with our new health care law.

We should remember these lessons we learned from the Challenger disaster. The Healthcare.gov rollout debacle was no less anticipated and certainly no less spectacular. We need a root cause analysis of this mess. We need to identify the problems and fix them if they can be fixed or scrap what can't. We should stop and ask ourselves what of this law should continue, and what should be scraped. We should ask the difficult questions and if it truly is in our best interest to proceed with certain parts, test and retest that which remains to make sure the systems are secure and the program functional. And most of all, we should ask now if this whole grand health care idea is likely to be truly cost effective and sustainable for our nation before rushing ahead toward another disaster.

Because, like the Challenger, it's people's lives we're talking about here, not some stupid website catastrophe.

-Wes

Sign up people. No worries.

Even if they take you to the cleaners.

It was interesting reading the piece over at Kaiser Health News asking why a couple without kids has to buy dental insurance for children they don't have. Or the free colonoscopy "catch" never discussed in the Obamacare ads that promoted by the law's proponents. More and more of these not-so-little details are not as pretty and "free" as everyone had hoped, but it's what we as a nation have approved, hidden in the new law we never read.

Shame on us.

Shame on our legislators.

But we must take a different perspective now that it's becoming crystal clear what central control of health care delivery means. I think most Americans have been incredibly tolerant of the rollout (and even appreciate the effort involved) since they have a rudimentary understanding of how complicated health care has become in America and how vital it is to our economy.

But I sense (like many others) that Americans' patience is growing thin. People are wondering how will things be fixed? How long will it take? Will I have to pay a penalty for something so fraught with problems? Who's responsible? Whom can I call? Can they be trusted? Is this going to be how the rest of the health care coverage rollout happens?

Years ago, millions of people watched the US space shuttle Challenger explode into a million tiny pieces on a crystal clear day shortly after its launch. We were shocked at first, then deeply saddened, for our idealized notion of the space program so advanced and amazing quickly evaporated before our eyes. We grieved with the crew's families as we watched in horror the events replayed on TV again and again and again.

But then what happened? Investigations followed. Video tapes were reviewed. A root cause analysis was undertaken. Ideas were tested, the O-ring problem identified, and slowly, carefully, changes were made to the shuttle program. New parts were engineered, other parts scraped. More thorough testing than ever before occurred. Then re-testing. And slowly, cautiously, the shuttle program resumed, one baby step at a time.

And no one ever took a complicated shuttle launch for granted again.

So, too, should it be with our new health care law.

We should remember these lessons we learned from the Challenger disaster. The Healthcare.gov rollout debacle was no less anticipated and certainly no less spectacular. We need a root cause analysis of this mess. We need to identify the problems and fix them if they can be fixed or scrap what can't. We should stop and ask ourselves what of this law should continue, and what should be scraped. We should ask the difficult questions and if it truly is in our best interest to proceed with certain parts, test and retest that which remains to make sure the systems are secure and the program functional. And most of all, we should ask now if this whole grand health care idea is likely to be truly cost effective and sustainable for our nation before rushing ahead toward another disaster.

Because, like the Challenger, it's people's lives we're talking about here, not some stupid website catastrophe.

-Wes

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Obamacare 2016: Happy Yet?

From Bradley Allen, MD in the opinion section of the Wall Street Journal this morning:

-Wes

"The forecast shortage of doctors has become a real problem. It started in 2014 when the ACA cut $716 billion from Medicare to accommodate 30 million newly "insured" people through an expansion of Medicaid. More important, the predicted shortage of 42,000 primary-care physicians and that of specialists (such as heart surgeons) was vastly underestimated. It didn't take into account the ACA's effect on doctors retiring early, refusing new patients or going into concierge medicine. These estimates also ignored the millions of immigrants who would be seeking a physician after having been granted legal status.Read the whole thing (subscription required, sorry). Not surprisingly, it's not pretty.

It is surprising that the doctor shortage was not better anticipated: After all, when Massachusetts mandated health insurance in 2006, the wait to see a physician in some specialties increased considerably, the shortage of primary-care physicians escalated and more doctors stopped accepting new patients. In 2013, the Massachusetts Medical Society noted waiting times from 50 days to 128 days in some areas for new patients to see an internist, for instance.

But doctor shortages are only the beginning.

Even before the ACA cut $716 billion from its budget, Medicare only reimbursed hospitals and doctors for 70%-85% of their costs. Once this cut further reduced reimbursements, and the ACA added stacks of paperwork, more doctors refused to accept Medicare: It just didn't cover expenses.

Then there is the ACA's Medicare (government) board that dictates and rations care, and the board has begun to cut reimbursements. Some physicians now refuse even to take patients over 50 years old, not wanting to be burdened with them when they reach Medicare age. Seniors aren't happy."

Medicaid in 2016 has similar problems. A third of physicians refused to accept new Medicaid patients in 2013, and with Medicaid's expansion and government cuts, the numbers of doctors who don't take Medicaid skyrocketed. The uninsured poor now have insurance, but they can't find a doctor, so essentially the ACA was of no help.

The loss of private practice is another big problem. Because of regulations and other government disincentives to self employment, doctors began working for hospitals in the early 2000s, leaving less than half in private practice by 2013. The ACA rapidly accelerated this trend, so that now very few private practices remain."

-Wes

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Back to One

It was a comment posted by "Cat, MD" on my prior post regarding my assessment of where the nation stood "week two" following the launch of the government's health insurance exchange website that caught my eye. To me, she(?) asked what might be the one of the more important questions posed on this blog that warrants consideration by every medical student and practicing doctor currently:

Like a difficult case that stumps the best of doctors, perhaps doctors should go back to one.

The idea is not mine but that of the late psychologist and disruptive thinker, Sheldon B. Kopp. When a doctor has a difficult case sitting before them and they have run out of ideas about how to help that patient, he recommends the doctor go back to one. What do you know how to do well? What can you contribute to this patient. What have you tried that did not work?

Back to one.

From Dr. Kopp's book, "If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, Kill Him: The Pilgrimage Of Psychotherapy Patients:"

Of course, none of this is easy. It is not easy to take risks. It is not easy to think we might not just be able to sit back and ignore the difficulties that arise when biased third-parties control the show. But when we begin by going back to one, there is an opportunity for meaningful change that benefits doctors and patients alike.

For today's doctors, Dr. Kopp offers a useful visual:

To start, I believe there are a few prerequisites young and older doctors alike from either side of the political aisle should consider to help bring meaningful change to the health care reform discussion:

Be a Good Doctor: Nothing will improve your credibility as a spokesperson on behalf of your patients if you keep their interests first. This whole reform efforts is, after all, about them.

Get Involved: If you don't vote, you can't complain about who is elected. In the same way, if you don't get involved in voicing your concerns (and this is important) attempting to offer new, helpful solutions to problems faced by your patients, how will things ever improve for them?

Connect: None of us are politicians. None of us are lawyers (well, a few might hold dual degrees...). But doctors should be asking themselves, how have the politicians handled things to date? Maybe it's time to rethink our strategy for reform. Maybe Washington's solutions aren't our patient's best solutions. But is there a different way, an alternate strategy?

The vast majority of doctors are on the front line of caring for patients. Most are incredibly busy. And the majority are a devoted bunch with authority when it comes to patient care (believe it or not). We can offer solutions. Some are likely to fall on deaf ears, but some may not. But if we don't speak up and consistently advocate for our patients' medical needs over basic or mandated business concerns, our patients will suffer and we will be sidelined.

Some have suggested that social media might be a place where doctors' voices can be heard. Perhaps. But while doctors can voice our thoughts and ideas on social media, I am increasingly convinced that this is not where real change will occur. We need to bring our thoughts and ideas back home to our communities. Doctors need to take back medicine by going back to one and dig deep to offer small solutions one at a time locally, at home, not on some large bureaucratic national stage that is driven by special interests.

Cat, MD's question is the nugget: "... but how?" "Back to One" is just one idea. There are others. But maybe the best way to start changing health care for the better is to start asking the right questions and offering our own solutions for ourselves and our patients.

-Wes

Dr. Wes,Perhaps this would be as good a time as any to step back and contemplate this incredibly challenging question. After all, more and more difficulties with our new law are appearing as its real nuts and bolts are revealed. Yet it is always easy to criticize the myriad of events that are unfolding: the botched Healthcare.gov website, the creation of new donut holes of health care coverage, or the real life problems with the restrictive health care system model we're creating. What can doctors possibly do to help resolve these challenges?

You state that law and medicine do not mix, but it seems as if medical care will be driven by national politics for the indefinite future. The ACA and laws like it will directly affect how physicians can practice.

So what role should physicians try to play in this? The prospect of letting attorneys and accountants dictate medical practice unnerves me. But at the same time, few people go to medical school to become politicians. As a medical student, I feel that physicians need to be more involved in legislating, but how?

Like a difficult case that stumps the best of doctors, perhaps doctors should go back to one.

The idea is not mine but that of the late psychologist and disruptive thinker, Sheldon B. Kopp. When a doctor has a difficult case sitting before them and they have run out of ideas about how to help that patient, he recommends the doctor go back to one. What do you know how to do well? What can you contribute to this patient. What have you tried that did not work?

Back to one.

From Dr. Kopp's book, "If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, Kill Him: The Pilgrimage Of Psychotherapy Patients:"

“Crises marked by anxiety, doubt, and despair have always been those periods of personal unrest that occur at the times when a man is sufficiently unsettled to have an opportunity for personal growth. We must always see our own feelings of uneasiness as being our chance for "making the growth choice rather than the fear choice.”We have tried Red and Blue solutions for health care reform and should be asking ourselves how they are working out. What has worked? What hasn't? What can each of us bring to the health care table? What needs to be done? Is a centralized control of health care our best solution, or might there be something else?

Of course, none of this is easy. It is not easy to take risks. It is not easy to think we might not just be able to sit back and ignore the difficulties that arise when biased third-parties control the show. But when we begin by going back to one, there is an opportunity for meaningful change that benefits doctors and patients alike.

For today's doctors, Dr. Kopp offers a useful visual:

“There is the image of the man who imagines himself to be a prisoner in a cell. He stands at one end of this small, dark, barren room, on his toes, with arms stretched upward, hands grasping for support onto a small, barred window, the room's only apparent source of light. If he holds on tight, straining toward the window, turning his head just so, he can see a bit of bright sunlight barely visible between the uppermost bars. This light is his only hope. He will not risk losing it. And so he continues to staring toward that bit of light, holding tightly to the bars. So committed is his effort not to lose sight of that glimmer of life-giving light, that it never occurs to him to let go and explore the darkness of the rest of the cell. So it is that he never discovers that the door at the other end of the cell is open, that he is free. He has always been free to walk out into the brightness of the day, if only he would let go. (192)”If only we would let go.

To start, I believe there are a few prerequisites young and older doctors alike from either side of the political aisle should consider to help bring meaningful change to the health care reform discussion:

Be a Good Doctor: Nothing will improve your credibility as a spokesperson on behalf of your patients if you keep their interests first. This whole reform efforts is, after all, about them.

Get Involved: If you don't vote, you can't complain about who is elected. In the same way, if you don't get involved in voicing your concerns (and this is important) attempting to offer new, helpful solutions to problems faced by your patients, how will things ever improve for them?

Connect: None of us are politicians. None of us are lawyers (well, a few might hold dual degrees...). But doctors should be asking themselves, how have the politicians handled things to date? Maybe it's time to rethink our strategy for reform. Maybe Washington's solutions aren't our patient's best solutions. But is there a different way, an alternate strategy?

The vast majority of doctors are on the front line of caring for patients. Most are incredibly busy. And the majority are a devoted bunch with authority when it comes to patient care (believe it or not). We can offer solutions. Some are likely to fall on deaf ears, but some may not. But if we don't speak up and consistently advocate for our patients' medical needs over basic or mandated business concerns, our patients will suffer and we will be sidelined.

Some have suggested that social media might be a place where doctors' voices can be heard. Perhaps. But while doctors can voice our thoughts and ideas on social media, I am increasingly convinced that this is not where real change will occur. We need to bring our thoughts and ideas back home to our communities. Doctors need to take back medicine by going back to one and dig deep to offer small solutions one at a time locally, at home, not on some large bureaucratic national stage that is driven by special interests.

Cat, MD's question is the nugget: "... but how?" "Back to One" is just one idea. There are others. But maybe the best way to start changing health care for the better is to start asking the right questions and offering our own solutions for ourselves and our patients.

-Wes

Friday, October 18, 2013

Saying Goodbye to Drug Samples

Soon, doctors won't be handing patients drug samples from time to time, pharmacists will.

Doctors were told that makes a difference. It will soon be a national trend, they were told. Instead of handing a patient a sample, just type in an order for a sample to the EMR and the pharmacist will make sure they get it.

Doctors were told that the Joint Commission has certain standards that must be met by health care organizations and hospitals when drug samples are given to patients. After all, doctors were told by at least one of their own that drug company representatives bias the way doctors think and prescribe. Doctors must also disclose gifts they receive from drug companies that exceed $10, according to the recently activated Physician Payment Sunshine Act. Doctors were told drug samples might qualify as gifts. It just looks bad, they were told.

Doctors were not told that their hospital system runs the pharmacy now.

Think about that. Think about the unintended consequence when yet another small, kind, visible gesture that a doctor can make to his patient is yanked from his control. Think about the fact that decreasing pharmaceutical sales representatives might decrease pharmaceutical sales of more expensive medications, but might also have the unintended consequence of decreasing access to new and important information to physicians and as one study pointed out, result in doctors who didn't see drug representatives prescribing less effective and potentially more dangerous drugs to their patients longer than those who do.

But at least the sample order will be there in the electronic medical record to track. Hospitals will be in regulatory compliance and pass their Joint Commission inspections with flying colors. And no doubt the pharmacist will do a better job of teaching patients at the drug counter when people are lined up in public four-deep to get their prescriptions. Surely the hospital's pharmacist will be completely aware of the patient's entire medical history and offer the correct number of tracked sample medications without any conflict of interest involved.

And doctors will sleep better at night knowing their physician payment database record remains unblemished.

Yeah, no worries. None all all. It's all for the better good.

Really.

-Wes

Thursday, October 17, 2013

Accountable Care Act Week Two: An Honest Assessment, Part II

Bob Doherty, MD gives his assessment of the Accountable Care Act's second week over at the American College of Physician's blog today. It's a worthwhile read and I encourage my of my three readers to head over there to see what he has to say. Remarkably, I agree with some of his assessment, especially his perspective that the miserable launch of the ACA's healthcare.gov website is not a reason to call the law a complete "failure."

But as things would have it, the ACP blog does not permit the "html" tag in his blog comments (I understand why: it helps limit blog spam), but I wanted to reference a few important links so I'm placing my different "honest" assessment of our law's second week here. So Bob, please excuse my comment being left here.

But as things would have it, the ACP blog does not permit the "html" tag in his blog comments (I understand why: it helps limit blog spam), but I wanted to reference a few important links so I'm placing my different "honest" assessment of our law's second week here. So Bob, please excuse my comment being left here.

Bob --Wes

Politics and medicine don't mix, yet today the two combined are our reality. As such, a brief comment about your post.

First on what we agree upon: tech problems on healthcare.gov are not a reason to declare the ACA a “failure.” No doubt the day will come after they pour in many tens of millions of dollars more to fix the website that things will be humming along famously one day.

But many are aware that the ACA as it was written is no longer the ACA, so as such, it has failed before it's website was launched. But if we ignore this fact, the ACA now is a patchwork of political favors and waivers that favors the politically connected and architects of the law and it is likely to continue to be such. We are also finding that the law is very expensive for many Americans, yet does little to address the expanding cost burdens that health care imposes on America’s economy, especially when one evaluates the law on the basis of health care cost sustainability. To me, this is the ACA’s Achilles’ heel and why it will ultimately be morphed into yet another "law," not because of some poorly-designed website. You see, it is anything but “Affordable” and even more importantly, certainly not “sustainable.” But we should acknowledge that for many Americans saddled with the prospect of bankrupsy from burgeoning health care costs, the law will offer relief and this is a good thing.

Still, after the debut of the exchanges 1 October 2013, out-of-pocket costs of the new health care “plans” put forth by the insurance industry became known and were nicely outlined by Peter Frost in the Chicago Tribune recently. People will soon be feeling the effects of these additional costs first-hand that have been created in large part by the regulatory requirements of the law and its giant bureaucratic overhead. In fact, I have already begun hearing from patients that the deductibles for many of them are so high that many are worried they won’t meet their deductibles in an average health care year before the next year arrives. So what have they gained from this law, just a sense of altruism for their fellow man?

Personally, I think this is why the ACA as it exists will fail: Americans’ realized out-of-pocket health care costs. And when it does, Big Box medicine will have to accommodate new, innovative health care payment strategies that actually create visible value to those who pay into the system, rather than just guaranteeing the rising stock price of insurance and pharmaceutical companies.

But physicians like us are also to blame for the law’s ultimate failure. Caught between the law’s political promise of "health care coverage for all" now, versus creating more sustainable health care delivery system for the long run, our political lobbying groups (the AMA, ACP, ACC and others) sided with the political expediency of approving the law’s construct as it was presented. And so now, we have no choice but to continue to ride along on our newly revised Healthcare Hindenburg whether doctors really like it or not.

Just my two cents.

Monday, October 14, 2013

Sid Says Goodbye

Sid Schwab, MD, a surgeon with a remarkable skill as a writer and long-time author of Surgeonsblog (a favorite of mine in my early years as a blogger) says goodbye to the blog-o-sphere in true Sid-style.

-Wes

-Wes

Thursday, October 10, 2013

You Can't Say You Weren't Warned

He looked ahead, seeing his feet on the hearth. There was smoke rising from one of the three logs, and he marveled at the small flicker of flame that stretched up and ignited the smoke that swirled above the log, dancing briefly somewhat joyously, then gone again, smoke returning.

"You can't say you weren't warned," she said.

He sat, reflecting on her words. So much years of work, so much effort, breadwinner, worker, eager participant in so many others' life-and-death moments. That was his job, right? It was his aphrodisiac, his salve, his calling for so long. Always being there for others, on call with pager on, nurses and Emergency Rooms calling. But now, after the sun has long set in a quiet house with his wife and blind, loving cocker spaniel next to him, he reflected: "Where did the time go?"

"You can't say you weren't warned."

With that, the door opened. The young man entered, unshaven, hurried and preoccupied, but seemed happy. So much was happening, albeit it was his own separate calling, full of its own challenges and pressures. He sprung to his feet to greet the young man, remembering when he had been in a similar place at a much earlier time: anxious, uncertain, excited, like when he directed his the first real code - so much responsibility.

"Happy birthday, Dad," the young man said.

They hugged, shared a story together, then a piece of cake. Before he knew it, "I wish I could stay longer, but I have to go. I've still got a ton to do."

"I understand. You'll do fine. Thanks for coming over. Good luck." And after grabbing the remaining piece of cake to bring to his roommate, the young man left as quickly as he had come. His wife, exhausted after a long day herself, headed to bed and left him to close up for the night.

He went to the front door, placed his hand on the lock and stood for a moment. The porch light shone dimly on the front walkway as it had done for so many years, a guide for the inevitable late night arrival that would always enter later.

Until now.

The house stood eerily silent, a stark reminder of all that has happened while he was busy doing other things. He turned the lock, switched off the unnecessary porch light, then headed to bed as her words echoed:

"You can't say you weren't warned."

-Wes

"You can't say you weren't warned," she said.

He sat, reflecting on her words. So much years of work, so much effort, breadwinner, worker, eager participant in so many others' life-and-death moments. That was his job, right? It was his aphrodisiac, his salve, his calling for so long. Always being there for others, on call with pager on, nurses and Emergency Rooms calling. But now, after the sun has long set in a quiet house with his wife and blind, loving cocker spaniel next to him, he reflected: "Where did the time go?"

"You can't say you weren't warned."

With that, the door opened. The young man entered, unshaven, hurried and preoccupied, but seemed happy. So much was happening, albeit it was his own separate calling, full of its own challenges and pressures. He sprung to his feet to greet the young man, remembering when he had been in a similar place at a much earlier time: anxious, uncertain, excited, like when he directed his the first real code - so much responsibility.

"Happy birthday, Dad," the young man said.

They hugged, shared a story together, then a piece of cake. Before he knew it, "I wish I could stay longer, but I have to go. I've still got a ton to do."

"I understand. You'll do fine. Thanks for coming over. Good luck." And after grabbing the remaining piece of cake to bring to his roommate, the young man left as quickly as he had come. His wife, exhausted after a long day herself, headed to bed and left him to close up for the night.

He went to the front door, placed his hand on the lock and stood for a moment. The porch light shone dimly on the front walkway as it had done for so many years, a guide for the inevitable late night arrival that would always enter later.

Until now.

The house stood eerily silent, a stark reminder of all that has happened while he was busy doing other things. He turned the lock, switched off the unnecessary porch light, then headed to bed as her words echoed:

"You can't say you weren't warned."

-Wes

Daily Caller: 800 Number for HealthCare.gov - An Accident?

You can't make this stuff up: look what the 800 number for Heathcare.gov's information hotline spells. Goodness!

This can't be an accident. After all, it shows what can be found when you actually read the keypad...

-Wes

This can't be an accident. After all, it shows what can be found when you actually read the keypad...

-Wes

Wednesday, October 09, 2013

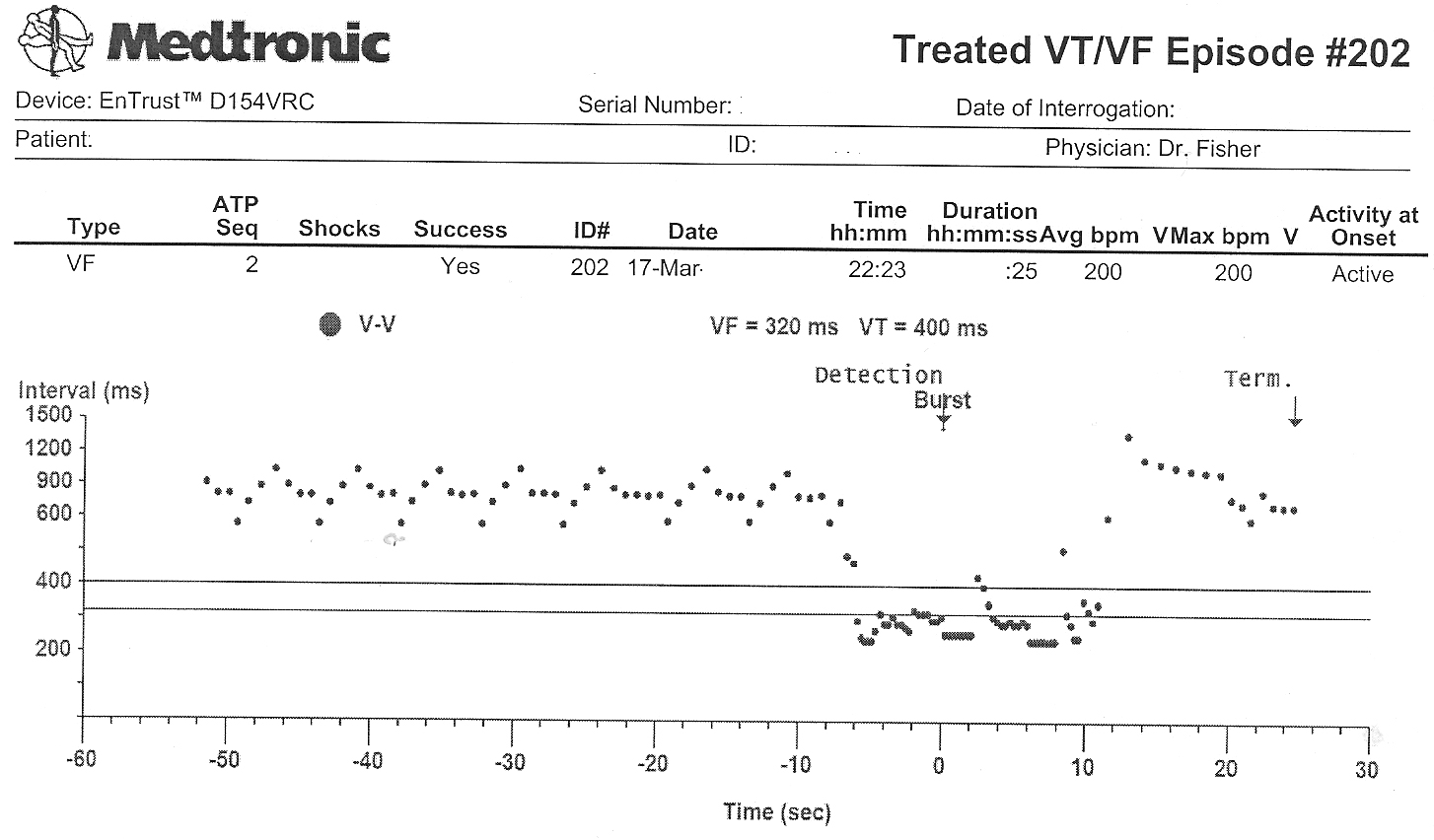

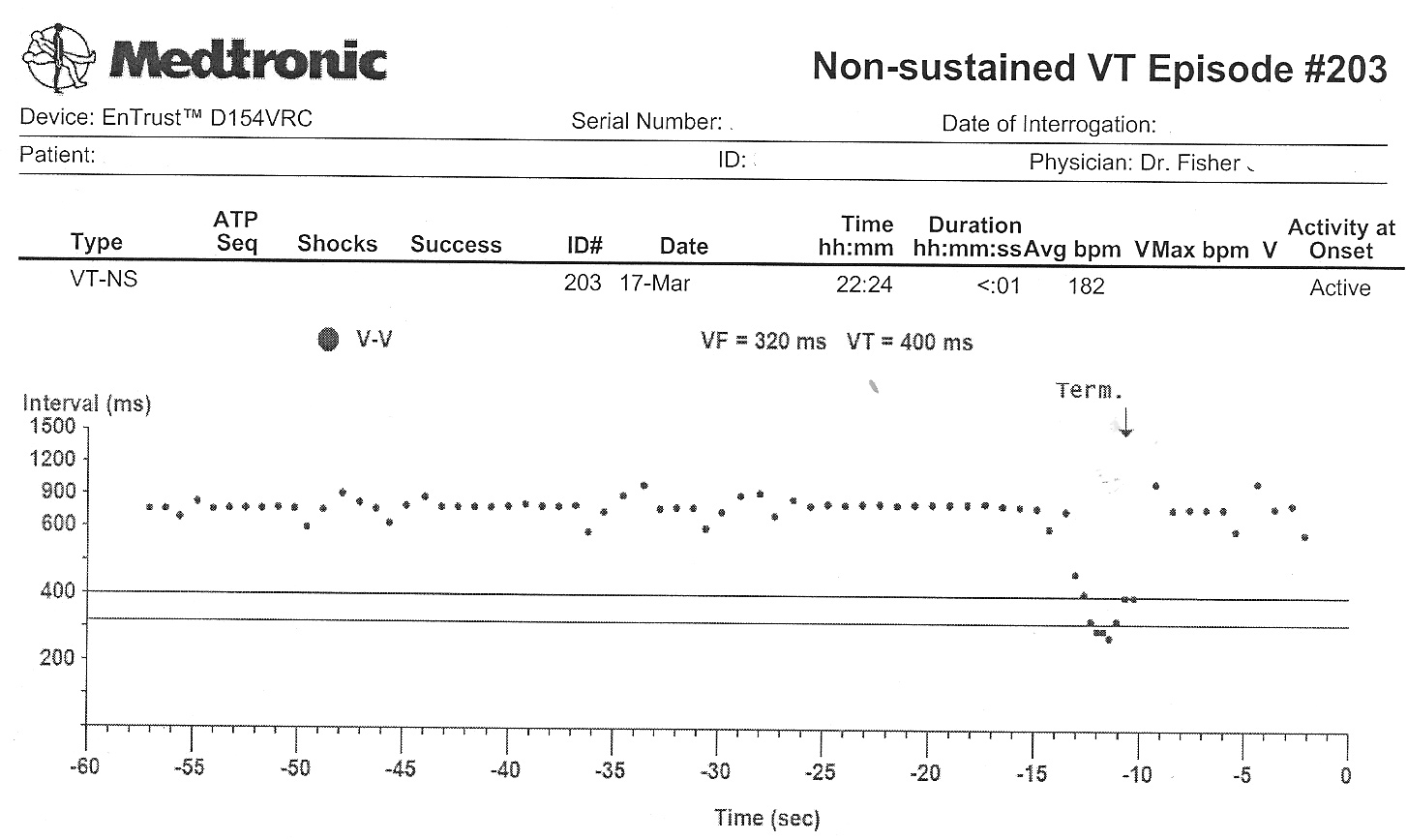

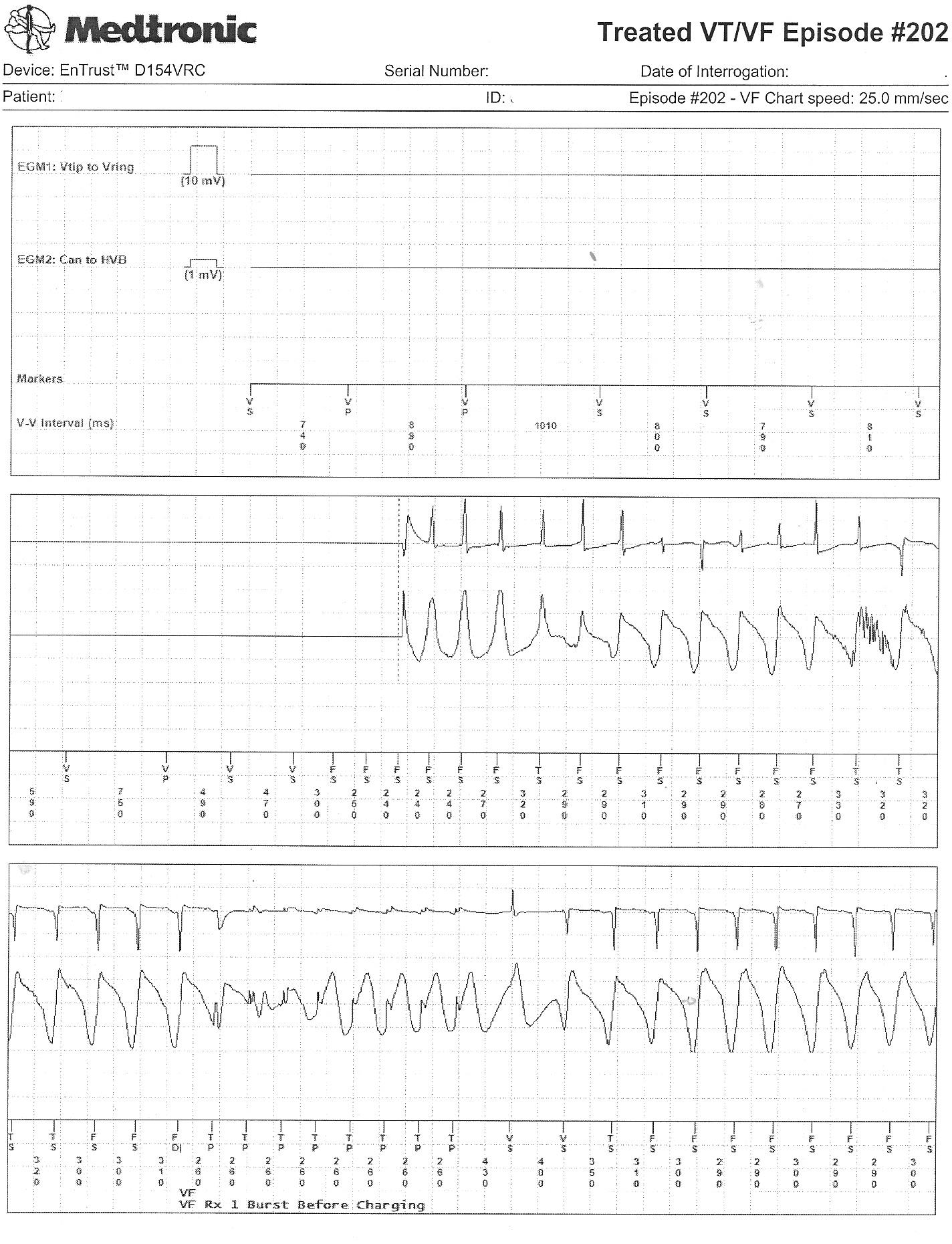

Case Study: A Case of Recurrent Ventricular Tachycardia

The following is a case study intended for folks who look at defibrillator recordings. If you find it interesting, great. If you have no clue what is shown here, don't feel bad, just move on to another blog post. I just thought I'd put this up as an unknown for those interested in phenomena encountered in a busy device clinic.

It was a case seen in our clinic: a nice man in his 50's had received a single chamber ICD for recurrent ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation and called because he had received several shocks from this device. Interrogation of the device showed normal sensing, lead impedance and capture threshold. Interrogation of his device demonstrated multiple VT therapies and untreated events recorded by his device.An example of several of the recorded interval plots (Event 202 and 203) as well has one example of the electrograms (and therapies delivered) recorded during episode 202 are shown below. 56 similar events were recorded since his last device interrogation, all with a similar pattern:

|

| Episode 202 RR Interval Plot (Click to enlarge) |

|

| Event 203 RR Interval Plot |

|

| Event 202's Recorded Electrograms and Intervals (Click image to enlarge) |

-Wes

Tuesday, October 08, 2013

What Board Recertification Is Failing to Teach Doctors

I continue to study for my third ABIM re-certifications in both cardiovascular disease and cardiac electrophysiology. In preparation for the examinations, I purchased the review materials offered by the American College of Cardiology called ACCSAP-8 and took the surprisingly expensive Cardiac Electrophysiology Board Review course held in Chicago recently. I find I have little time to study all of this material while delivering patient care, so I've been getting up at 4:30-5:00 am each day when by brain is rested to review the material. Needless to say, the material is so plentiful and dense that I feel like I'm reading through the Encyclopedia Britanica.

After studying for these boards for the third time, I have come to the realization that there's a million ways the ABIM could write test questions to pimp those of us required to re-take these exams. I can only hope that the few items I've learned as a consequence of answering the accompanying questions at the end of each section of the materials gets me by in a test whose curve is set by some statistical method that no one really understands. But what if I don't pass, God forbid? What would it mean for me professionally? While doctors are reassurred they can re-take the examination (for a fee, of course), does the ABIM's "scarlet letter" affect my ability to practice medicine? Should doctors be educated on the implications of non-certification and what it might mean to a doctor professionally rather than just touting the benefits of this process? Since the implications of not passing re-certification boards may have large financial and emotional implications to physicians, what ethical and legal responsibility does the ABIM and American Board of Medical Specialties hold to their members? I really don't know.

But my point in this post is not to re-hash my concerns about the non-objective and money-making nature of this recertification process, but rather to identify other problematic areas that the ABIM and professional societies like the American College of Cardiology and Heart Rhythm Society are missing in this re-certification process.

First of all, cardiology practice has changed. Cardiology specialists and subspecialists are now increasingly employees of huge health care systems as a result of the health care reform efforts underway. Increasingly, our subspecialties of cardiovascular medicine and cardiac electrophysiology are divided and continue to diverge clincially as knowledge and discovery expands at an unprecedented pace in both fields. As a result of these realities, there is little need any longer for electropysiologists to understand the nuanced differences between various glycoprotein GIIa/IIIb inhibitors, for instance. EPs just need to know that all of these drugs make patients' pacemaker pockets bleed more after surgery. Likewise, do electrophysiologists really need to know the differences between multi-detector CT and SPECT scanning protocols for the diagnostic evaluation of coronary disease in our new subspecialized world of medicine that remains far too litiginous? Electrophysiologists would be foolhardy to recommend a particular scan or the proper antiplatelet agent after a drug-eluting stent given these realities. Instead, doctors of varying skill areas need each other more than ever to provide quality care, not try to harbor every factoid in textbooks between our earlobes. To think any EP or cardiologist should (or could) know the ropes of the other specialty is unrealistic. As such, I continue to wonder why the added expense of cardiovascular medicine board recertification must be added on top of electrophysiology board recertification for tomorrow's doctors, especially in this era of Uptodate and Google. No matter that your view is of these arduous re-certification processes, we need to leverage technology to improve patient care and physician knowledge rather than pretend we don't need it. Force-feeding busy clnical doctors with more facts than they can ever hope to recall is frustrating, unnecessarily time-consuming, and may even have the unintended consequence of detracting from actual patient care delivery.

Secondly, ABIM re-certification test-writers fail to teach doctors how new CMS coding and billing requirements can adversely affect their colleagues and patients. For instance, no where is this more evident than the confusion that surrounds classification of patients coming to a hospital for "observation" or "inpatient" admission. As any skilled clinical doctor understands, what is billed and paid to the patient, doctor and hospital system rests heavily on this definition. Does the ABIM teach doctors this? No. Yet the financial and quality of care implications of this definition to both patients and doctors are very significant depending on how a patient stay in the hospital is defined by payers. (If you don't know this, dear doctor, you should.)

Thirdly, clinical physicians can even teach the more academic ABIM members a thing or two. For instance, maybe doctors who actually care for patients could insist that ABIM members teach doctors how to use vascular ultrasound devices to improve the safety of vascular access for our patients. Why isn't such a skill taught by our board reviewers who claim they are interested in improved patient outcomes? Might it be because it requires each of us to actually touch and care for a patient, something we get pretty good at after thirty years of providing care? Requiring academic discussions of obscure genetic disorders might make for good test fodder, but such obscure instruction completely misses important aspects of physician competency and patient safety.

This is not to say that all academic learning in medicine is without utility. On the contrary, learning by physicians will always remain an essential aspect of caring for our patients. I know that the many excellent doctors that have written modules for board certification preparation purposes have made every effort to make the re-certification process as meaningful as possible for doctors. But we should acknowledge that all doctors already have to "prove" that we participate in learning when we have to submit "certified" CME certificates to maintain licensure. Every doctor in America constantly has to "prove" we don't hurt people to our quality assurance committees and to the legal community. To force additional expensive and unproven training that is out of touch in so many ways with the way medical care is being delivered now may be having significant unintended negative consequences, too. We should start asking if the ABIM could be causing more harm than good as doctors become increasingly frustrated by the many bureaucratic and administrative hoops that increasingly detract from patient care.

After all, it's the lack of time left in the day to care for our patients that's most likely to harm them, not whether we pass a test or not.

-Wes

After studying for these boards for the third time, I have come to the realization that there's a million ways the ABIM could write test questions to pimp those of us required to re-take these exams. I can only hope that the few items I've learned as a consequence of answering the accompanying questions at the end of each section of the materials gets me by in a test whose curve is set by some statistical method that no one really understands. But what if I don't pass, God forbid? What would it mean for me professionally? While doctors are reassurred they can re-take the examination (for a fee, of course), does the ABIM's "scarlet letter" affect my ability to practice medicine? Should doctors be educated on the implications of non-certification and what it might mean to a doctor professionally rather than just touting the benefits of this process? Since the implications of not passing re-certification boards may have large financial and emotional implications to physicians, what ethical and legal responsibility does the ABIM and American Board of Medical Specialties hold to their members? I really don't know.

But my point in this post is not to re-hash my concerns about the non-objective and money-making nature of this recertification process, but rather to identify other problematic areas that the ABIM and professional societies like the American College of Cardiology and Heart Rhythm Society are missing in this re-certification process.

First of all, cardiology practice has changed. Cardiology specialists and subspecialists are now increasingly employees of huge health care systems as a result of the health care reform efforts underway. Increasingly, our subspecialties of cardiovascular medicine and cardiac electrophysiology are divided and continue to diverge clincially as knowledge and discovery expands at an unprecedented pace in both fields. As a result of these realities, there is little need any longer for electropysiologists to understand the nuanced differences between various glycoprotein GIIa/IIIb inhibitors, for instance. EPs just need to know that all of these drugs make patients' pacemaker pockets bleed more after surgery. Likewise, do electrophysiologists really need to know the differences between multi-detector CT and SPECT scanning protocols for the diagnostic evaluation of coronary disease in our new subspecialized world of medicine that remains far too litiginous? Electrophysiologists would be foolhardy to recommend a particular scan or the proper antiplatelet agent after a drug-eluting stent given these realities. Instead, doctors of varying skill areas need each other more than ever to provide quality care, not try to harbor every factoid in textbooks between our earlobes. To think any EP or cardiologist should (or could) know the ropes of the other specialty is unrealistic. As such, I continue to wonder why the added expense of cardiovascular medicine board recertification must be added on top of electrophysiology board recertification for tomorrow's doctors, especially in this era of Uptodate and Google. No matter that your view is of these arduous re-certification processes, we need to leverage technology to improve patient care and physician knowledge rather than pretend we don't need it. Force-feeding busy clnical doctors with more facts than they can ever hope to recall is frustrating, unnecessarily time-consuming, and may even have the unintended consequence of detracting from actual patient care delivery.

Secondly, ABIM re-certification test-writers fail to teach doctors how new CMS coding and billing requirements can adversely affect their colleagues and patients. For instance, no where is this more evident than the confusion that surrounds classification of patients coming to a hospital for "observation" or "inpatient" admission. As any skilled clinical doctor understands, what is billed and paid to the patient, doctor and hospital system rests heavily on this definition. Does the ABIM teach doctors this? No. Yet the financial and quality of care implications of this definition to both patients and doctors are very significant depending on how a patient stay in the hospital is defined by payers. (If you don't know this, dear doctor, you should.)

Thirdly, clinical physicians can even teach the more academic ABIM members a thing or two. For instance, maybe doctors who actually care for patients could insist that ABIM members teach doctors how to use vascular ultrasound devices to improve the safety of vascular access for our patients. Why isn't such a skill taught by our board reviewers who claim they are interested in improved patient outcomes? Might it be because it requires each of us to actually touch and care for a patient, something we get pretty good at after thirty years of providing care? Requiring academic discussions of obscure genetic disorders might make for good test fodder, but such obscure instruction completely misses important aspects of physician competency and patient safety.

This is not to say that all academic learning in medicine is without utility. On the contrary, learning by physicians will always remain an essential aspect of caring for our patients. I know that the many excellent doctors that have written modules for board certification preparation purposes have made every effort to make the re-certification process as meaningful as possible for doctors. But we should acknowledge that all doctors already have to "prove" that we participate in learning when we have to submit "certified" CME certificates to maintain licensure. Every doctor in America constantly has to "prove" we don't hurt people to our quality assurance committees and to the legal community. To force additional expensive and unproven training that is out of touch in so many ways with the way medical care is being delivered now may be having significant unintended negative consequences, too. We should start asking if the ABIM could be causing more harm than good as doctors become increasingly frustrated by the many bureaucratic and administrative hoops that increasingly detract from patient care.

After all, it's the lack of time left in the day to care for our patients that's most likely to harm them, not whether we pass a test or not.

-Wes

Monday, October 07, 2013

When the Best Stuff Ends Up on Twitter

Keeping a blog, I feel like a dinosaur, but I do it because it's a place I can return to to find a thought.

I think, I write, I put some thoughts down in this space. The piece is published here and then "fed" to Twitter and to an "RSS feed" for wider distribution. People then come here and read the piece. People like the thought. Others hate it. So what do they do? They "retweet with comment" on Twitter (or Facebook) and their view evaporates in seconds to another social media space.

It's an interesting phenomenon, and perhaps one brought on by multiple social media outlets and voluminous comment "spam-bots" that have led folks like me to have to implement difficult "Captcha" screens to limit the garbage that can appear in the comments section of blogs. (Some IT spam marketing experts have discovered how to break Captcha screens, too).

Oh sure, I could put a live stream of Twitter comments on my sidebar, but as the Twitter feed scrolls on with time, the insightful (and often helpful) thoughts are lost into the void of the inter-webs. The conversation dies quickly and many people who read the post later miss those thoughts.

Does anyone know an easy way to automatically add Twitter "re-tweets with comments" that occur on Twitter to the comments of an individual blog post? This might help solve this conundrum.

In the meantime, consider taking a second to leave your comments here for others to read so your brilliant thoughts don't evaporate in seconds into the Internet ether.

After all, your thoughts matter in "social" media, remember?

-Wes

I think, I write, I put some thoughts down in this space. The piece is published here and then "fed" to Twitter and to an "RSS feed" for wider distribution. People then come here and read the piece. People like the thought. Others hate it. So what do they do? They "retweet with comment" on Twitter (or Facebook) and their view evaporates in seconds to another social media space.

It's an interesting phenomenon, and perhaps one brought on by multiple social media outlets and voluminous comment "spam-bots" that have led folks like me to have to implement difficult "Captcha" screens to limit the garbage that can appear in the comments section of blogs. (Some IT spam marketing experts have discovered how to break Captcha screens, too).

Oh sure, I could put a live stream of Twitter comments on my sidebar, but as the Twitter feed scrolls on with time, the insightful (and often helpful) thoughts are lost into the void of the inter-webs. The conversation dies quickly and many people who read the post later miss those thoughts.

Does anyone know an easy way to automatically add Twitter "re-tweets with comments" that occur on Twitter to the comments of an individual blog post? This might help solve this conundrum.

In the meantime, consider taking a second to leave your comments here for others to read so your brilliant thoughts don't evaporate in seconds into the Internet ether.

After all, your thoughts matter in "social" media, remember?

-Wes

Friday, October 04, 2013

How to Solve the Doctor Burn-out Problem

A piece recently appeared in the New York Times entitled "Who Will Heal the Doctors?" The piece is written by Donald Borstein and I encourage all to read it. Mr. Bornstein offers a solution to the doctor burnout problem in health care, a course called The Healers Art, now being promoted in US medical schools that uses "mindfulness" as his means of creating compassionate, caring doctors as a way forward.

I should say at the outset, that I do not disagree with the concept that doctors should not be more attuned to the circumstances for which they are being trained. But the overall argument that such "mindfulness" practices can repair his so called "McDonaldization of Medicine" is somewhat disingenuous concept. It skirts the very real challenges doctors have today when caring for patients and the many layers of bureaucracy and paperwork, both electronic and manual, along with the hidden costs that their patients are subject to as a result of doctor orders entered on a computer as they try to follow certain care "standards." Blind-siding one's patients doesn't make for the best of relations. Still, as bad as these realities are, they are probably not the reason most doctors are turning away from medicine. I think there's another issue that is even bigger.

I believe the overriding reason doctors leave medicine is because there is a growing hostile dependency patients have toward their doctors.

I have mentioned this concept of hostile dependency before. The theme is like an adolescent who realizes his parents have feet of clay. In adolescence, he comes out of his childhood bubble and realizes his parents have failures and limitations because they are human beings. This results in the adolescent feeling unsafe, unprotected and vulnerable. Since this is not a pleasant feeling, narcissistic rage is triggered toward the people he needs and depends on the most. Yet (and this is important) none of this occurs at a conscious level. Most of us understand this behavior simply as "adolescent rebellion," not understanding the powerful issues at play. So when we spotlight doctor burnout, or, say, the lack of patient safety in hospitals without acknowledging the realities health care workers face like looming staffing shortages and pay cuts, we risk fanning the flames of narcissistic rage against the very caregivers whom we depend on the most - the very caregivers who are striving to do more with less, check boxes while still looking in the patient's eyes, meet productivity ratios, all while working in a highly litigious environment.

A comment from "Victor Edwards" posted after Mr. Bornstein's article demonstrates this growing hostile dependency toward doctors perfectly:

Yet this is what we're creating with our increasingly consolidated "McDonaldization" of medicine. Given where things are heading, I'm not sure this will be an easy fix as doctors are shoved farther away from the patients. But let me be perfectly clear: if you want to keep doctors from getting burned out quickly in medicine, it is this growing hostile dependency that patients have toward their doctors that must be addressed head-on.

-Wes

I should say at the outset, that I do not disagree with the concept that doctors should not be more attuned to the circumstances for which they are being trained. But the overall argument that such "mindfulness" practices can repair his so called "McDonaldization of Medicine" is somewhat disingenuous concept. It skirts the very real challenges doctors have today when caring for patients and the many layers of bureaucracy and paperwork, both electronic and manual, along with the hidden costs that their patients are subject to as a result of doctor orders entered on a computer as they try to follow certain care "standards." Blind-siding one's patients doesn't make for the best of relations. Still, as bad as these realities are, they are probably not the reason most doctors are turning away from medicine. I think there's another issue that is even bigger.

I believe the overriding reason doctors leave medicine is because there is a growing hostile dependency patients have toward their doctors.

I have mentioned this concept of hostile dependency before. The theme is like an adolescent who realizes his parents have feet of clay. In adolescence, he comes out of his childhood bubble and realizes his parents have failures and limitations because they are human beings. This results in the adolescent feeling unsafe, unprotected and vulnerable. Since this is not a pleasant feeling, narcissistic rage is triggered toward the people he needs and depends on the most. Yet (and this is important) none of this occurs at a conscious level. Most of us understand this behavior simply as "adolescent rebellion," not understanding the powerful issues at play. So when we spotlight doctor burnout, or, say, the lack of patient safety in hospitals without acknowledging the realities health care workers face like looming staffing shortages and pay cuts, we risk fanning the flames of narcissistic rage against the very caregivers whom we depend on the most - the very caregivers who are striving to do more with less, check boxes while still looking in the patient's eyes, meet productivity ratios, all while working in a highly litigious environment.

A comment from "Victor Edwards" posted after Mr. Bornstein's article demonstrates this growing hostile dependency toward doctors perfectly:

Doctors? I no longer afford that kind of respect: I call them "medical services providers." They and their families and the medical cabal created this mess when they got control of med schools so that the wealth of a nation would remain in the hands of a few medical elites and their families. The very notion that doctors are smarter, more productive, more anything than others is ludicrous. They are among the worst sluff-offs of our society, yet the richest at the same time. It is an unreal world they have created themselves and they are now watching the natural outcome of such a false system.How do we fix this attitude toward doctors? Who would want to work in an environment where patients perceive their doctors so?

Yet this is what we're creating with our increasingly consolidated "McDonaldization" of medicine. Given where things are heading, I'm not sure this will be an easy fix as doctors are shoved farther away from the patients. But let me be perfectly clear: if you want to keep doctors from getting burned out quickly in medicine, it is this growing hostile dependency that patients have toward their doctors that must be addressed head-on.

-Wes

Tuesday, October 01, 2013

Ten Crackers

Graham crackers.

For years they have been an on-call snack staple for young doctors in training throughout the United States. These little morsels have probably saved more lives than defibrillators after hours, especially if they are topped with a hefty dollop of peanut butter.

Admittedly, these flat brown crispy tastees don't contain much nutritional value. They are probably a dentist's nightmare. But after many late hours on call well after the dining hall closes, you'd be surprised how good these little devils taste, especially when they can be enjoyed in a quiet reflective moment alone or with a colleague in the nutrition room. Graham crackers have a way of bringing you back to earth after you've dealt with a code, had to pronounce someone dead, or worked through a difficult family interaction in the wee hours of the morning.

But times are tough for hospitals now: censuses are down (as are revenues) as the uncertain effects of health care reform descend. Consequently, it makes sense for hospitals to trim budgets where they can. After all, if its between graham crackers or nurses, I'm sure we'd all agree that graham crackers should be trimmed before nursing staff.

But I wonder if supplying an entire ward of fifty patients with only 10 of these little packets a day makes sense for physician and nursing morale. Doctors and nurses, already dealing with reduced incomes and threatened with even more to come, are finding it harder and harder to find the tiny perks that make the late nights and long weekends tolerable. Finding none of these hidden snack treasures on a ward after working 15 hours straight certainly isn't the end of the world, but when people are tired and hungry, it's noticed more than any highly-paid administrative decision-maker who's tucked neatly in bed could ever imagine.

Good leaders listen.

Good leaders know the value of small gestures.

But it's only the best of leaders that appreciate the importance of an ample supply of graham crackers.

-Wes

For years they have been an on-call snack staple for young doctors in training throughout the United States. These little morsels have probably saved more lives than defibrillators after hours, especially if they are topped with a hefty dollop of peanut butter.

Admittedly, these flat brown crispy tastees don't contain much nutritional value. They are probably a dentist's nightmare. But after many late hours on call well after the dining hall closes, you'd be surprised how good these little devils taste, especially when they can be enjoyed in a quiet reflective moment alone or with a colleague in the nutrition room. Graham crackers have a way of bringing you back to earth after you've dealt with a code, had to pronounce someone dead, or worked through a difficult family interaction in the wee hours of the morning.

But times are tough for hospitals now: censuses are down (as are revenues) as the uncertain effects of health care reform descend. Consequently, it makes sense for hospitals to trim budgets where they can. After all, if its between graham crackers or nurses, I'm sure we'd all agree that graham crackers should be trimmed before nursing staff.

But I wonder if supplying an entire ward of fifty patients with only 10 of these little packets a day makes sense for physician and nursing morale. Doctors and nurses, already dealing with reduced incomes and threatened with even more to come, are finding it harder and harder to find the tiny perks that make the late nights and long weekends tolerable. Finding none of these hidden snack treasures on a ward after working 15 hours straight certainly isn't the end of the world, but when people are tired and hungry, it's noticed more than any highly-paid administrative decision-maker who's tucked neatly in bed could ever imagine.

Good leaders listen.

Good leaders know the value of small gestures.

But it's only the best of leaders that appreciate the importance of an ample supply of graham crackers.

-Wes

Welcome to the New Health Care

As seen a Boston Logan airport this weekend:

As of 10:15 pm on 30 Sep 2013, the official Illinois insurance exchange website with its reported 165 options for health care coverage called GetCoveredIllinois.gov (and run by the Federal government) has yet to launch.

I wish I could have critiqued the site and the health plan offerings with their out-of-pocket costs for the Big Day.

But it was not to be.

The great irony in all of this is that really, nothing is new. Everything, it seems, remains cloaked in secrecy.

Oh sure there are things called "exchanges" now. And millions upon millions of dollars will be spent on internet, social media, TV, print, and radio advertising touting the law. There will be counselors there to help people make an "informed" choice. But there's still a new complicated, unreadable law that promises much, but delivers, well, we're still not really sure. There have been so many promises, but no one knows (yet) what we've given up in return for the monstrous bureaucracy, new payments, and massive consolidation of doctors offices and hospital systems that this law has already created. Oh sure, the least risky adult population under 26 can stay on insurance, but now millions of young people who make $20,000 per year will be signing up for something that costs one tenth of their salary annually ($163 / month x 12) and have no idea in the world what they're getting (really) for their money. Oh, sure, they get well doctor visits, but what does Insurance Company B have over Insurance Company C, or company Z? Why do people have to add a zip code on their websites - have some areas gotten political favors in exchange for lower costs when others don't?

No one has a clue.

And that will total out of pocket costs really be in terms of "co-pays" and "co-insurance" kick in? What happens when an insurance company refuses to pay for a service because it wasn't the service they chose for people covered in their plans?

No one has a clue.

And how long will people have to wait for an appointment after 1 January 2014 for their Medicaid care, in a system that already can't pay its bills? If my clinic's any indication: today, this minute, it's already a two and a half month wait for a routine follow-up appointment.

You see, there are only so many of us, and millions more patients on their way to Great Expectations now. But as the new law has been taking shape, there has been downsizing, trimming of staff, more work for those who remain, and lots of doctors and nurses dropping out, moving on, or retiring early because they've been given sweet deals, or really had no choice. Many are already frustrated, burned out, or getting to the point (sadly) that they really don't care any more as more an more administrators are hired to tell health care workers how to work without doing the real work themselves.

So things will have to change under they weight of it all and they will.

But for now, it's all "new," so enjoy.

-Wes

|

| Welcome to the New Health Care (Click to enlarge) |

I wish I could have critiqued the site and the health plan offerings with their out-of-pocket costs for the Big Day.

But it was not to be.

The great irony in all of this is that really, nothing is new. Everything, it seems, remains cloaked in secrecy.

Oh sure there are things called "exchanges" now. And millions upon millions of dollars will be spent on internet, social media, TV, print, and radio advertising touting the law. There will be counselors there to help people make an "informed" choice. But there's still a new complicated, unreadable law that promises much, but delivers, well, we're still not really sure. There have been so many promises, but no one knows (yet) what we've given up in return for the monstrous bureaucracy, new payments, and massive consolidation of doctors offices and hospital systems that this law has already created. Oh sure, the least risky adult population under 26 can stay on insurance, but now millions of young people who make $20,000 per year will be signing up for something that costs one tenth of their salary annually ($163 / month x 12) and have no idea in the world what they're getting (really) for their money. Oh, sure, they get well doctor visits, but what does Insurance Company B have over Insurance Company C, or company Z? Why do people have to add a zip code on their websites - have some areas gotten political favors in exchange for lower costs when others don't?

No one has a clue.

And that will total out of pocket costs really be in terms of "co-pays" and "co-insurance" kick in? What happens when an insurance company refuses to pay for a service because it wasn't the service they chose for people covered in their plans?

No one has a clue.

And how long will people have to wait for an appointment after 1 January 2014 for their Medicaid care, in a system that already can't pay its bills? If my clinic's any indication: today, this minute, it's already a two and a half month wait for a routine follow-up appointment.

You see, there are only so many of us, and millions more patients on their way to Great Expectations now. But as the new law has been taking shape, there has been downsizing, trimming of staff, more work for those who remain, and lots of doctors and nurses dropping out, moving on, or retiring early because they've been given sweet deals, or really had no choice. Many are already frustrated, burned out, or getting to the point (sadly) that they really don't care any more as more an more administrators are hired to tell health care workers how to work without doing the real work themselves.

So things will have to change under they weight of it all and they will.

But for now, it's all "new," so enjoy.

-Wes